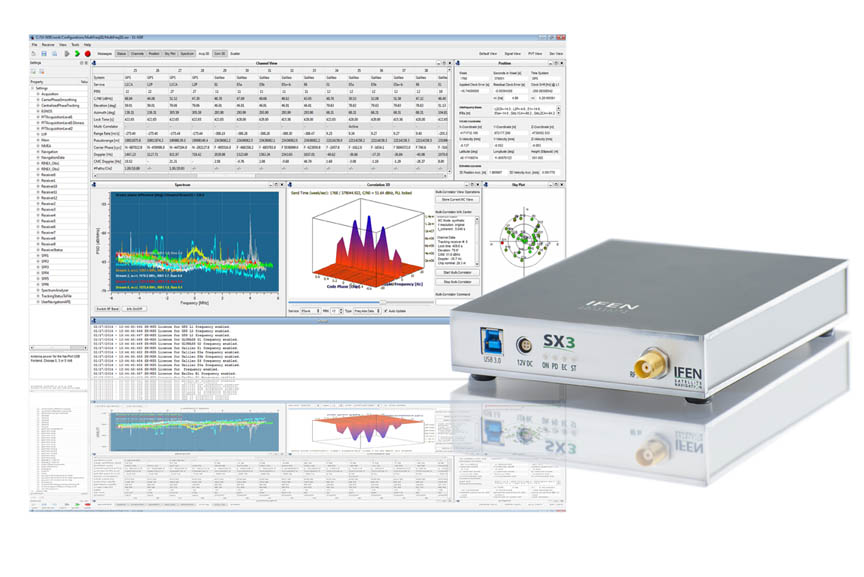

IFEN Launches SX3 Software Receiver

IFEN SX3

IFEN SX3IFEN introduced its new SX3 GNSS software receiver, a major upgrade of the company’s SX-NSR, last week at the ION GNSS+ conference in Tampa, Florida. Redesigned hardware frontends feature four wideband RF frequency bands that can be split into a maximum of eight sub-bands per unit. At the same time the bandwidth has been expanded to a full 55 megahertz, offering additional signal power especially in the Galileo E5 band.

By Inside GNSS