Making Virtual Solid

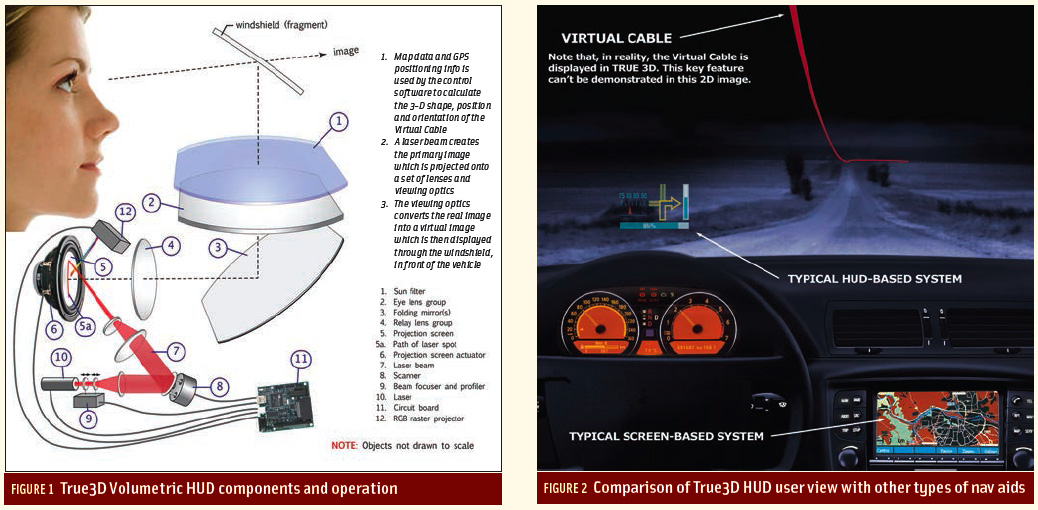

FIGURES 1 & 2: True3D Volumetric HUD components and operation (left), Comparison of True3D HUD user view with other types of nav aids (right)

FIGURES 1 & 2: True3D Volumetric HUD components and operation (left), Comparison of True3D HUD user view with other types of nav aids (right)Return to main article: "True3D HUD Wins Global SatNav Competition"

Many technologies are created before their best applications are even thought about. This leads to a business phenomenon known as “technology push” in contrast to “consumer pull.” The True3D Volumetric HUD technology did not share this path.

By Inside GNSS