Space debris poses a danger to PNT. Here’s a look at the threat and how the FCC plans to regulate its removal.

The resilience of the Global Navigation and Satellite System (GNSS) that enables mission and life-critical position, navigation and timing (PNT) remains a topic of interest around the world. Threats to PNT continue to increase exponentially. Space-based threats rank high among them, including space debris.

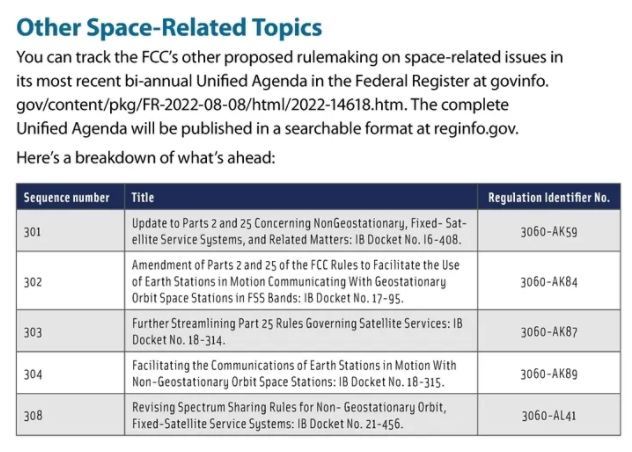

Recently, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) caused a bit of a stir by indicating it plans to issue regulations governing activities in space that currently fall between jurisdictional policy lines, including on the controversial matter of debris removal. Will there be clarity on this issue for the PNT industry soon despite the clutter among the stars and in the halls of government?

The Threat Spectrum

Earth’s orbit, home to GNSS satellite constellations, continues to grow increasingly crowded. According to the most recent statistics from the European Space Agency (ESA), humankind has launched about 13,630 satellites into Earth’s orbit since 1957, the beginning of the Space Age. Of those, almost 9,000 still remain.

While the majority are functional, more than 2,500 defunct satellites also continue to zip around in orbit. They have become nothing more than very large pieces of debris, which may break up, explode, collide or be involved in an event that results in fragmentation.

Such mayhem has already occurred. The first documented case of the destruction of an operational satellite after a collision with a defunct satellite happened in early 2009. In that case, an inactive Russian military communications satellite destroyed an American Iridium 33 communications satellite. The impact blew both satellites apart. The ESA estimates more than 630 of the currently defunct satellites in orbit may be involved in similar events.

Add this to an environment already littered with hunks of other dangerous junk. The space surveillance networks regularly catalog and track 36,500 objects of debris larger than 4 inches across. But not all objects are tracked. Based on statistical models, ESA estimates there are 1 million chunks of space debris from 0.4 inches to 4 inches and 130 million from .04 to 0.4 inches. The total mass of this space garbage is estimated to weigh in at more than 10,000 tons.

The problem will continue to get worse. Computer simulations project that space trash between 4 and 8 inches may multiply 3.2 times over the next 200 years. These same models predict debris less than 4 inches will increase even more, by a factor of 13 to 20.

This raises serious concerns for PNT resilience. While the danger of satellite-to-satellite impacts may be obvious, even a tiny fragment of debris in space can cause catastrophic damage to satellites. These objects often travel faster than a speeding bullet, at speeds of more than 22,300 miles per hour. This can lead to satellite destruction and result in fragmentation.

Growing orbital congestion also increases the risk of unintentional radio frequency interference.

For these reasons, the costs of mitigating space debris continue to add up. In addition to costs associated with tracking it, companies and governments pay a hefty price for design measures, dodging space debris in orbit or scrubbing missions entirely. Considering a GPS III satellite costs $400 million or more to build, an ounce of prevention may be worth the potential financial losses of a collision.

A Big Cluster

From a policy standpoint, space debris remains an unsolved global issue. Space law consists primarily of international agreements, treaties, conventions, and United Nations General Assembly resolutions and rules and regulations of international organizations. None of these explicitly forbid the production of space debris. They also don’t indicate who is responsible for removing it.

For example, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty imposes general responsibilities on member states for national activities to ensure they are conducted in conformity with the treaty (with the premise of freedom for exploration by all), to authorize and continually supervise its activities, and to share international responsibility for activities in which the state is a participant. Article VIII provides that a state “shall retain jurisdiction” and control over its objects. Most interpret this as including debris. Thus, states and organizations make their own rules for dealing with debris.

In the United States, just this July, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released the National Orbital Debris Mitigation Plan to meet space sustainability priorities to mitigate, track and remediate debris. This new 14-page plan supports the overarching 2021 U.S. Space Priorities Framework and implements Space Policy Directive-3 (SPD-3).

Signed by former President Trump, SPD-3 was the nation’s first National Space Traffic Management Policy. It outlined key roles and responsibilities. The directive assigned the administrator of NASA as lead for efforts to update the U.S.’ Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices and to establish new guidelines for satellite design and operation to mitigate the effect of orbital debris on space activities.

NASA, the directive indicated, must do this in coordination with the secretaries of state, defense, commerce and transportation, and the director of national intelligence. In contrast to this coordination requirement, according to the directive, the NASA administrator must consult with the FCC chairman.

SPD-3 requires the secretaries of commerce and transportation to assess the suitability of incorporating these updated standards and best practices into their respective licensing processes—again, in consultation with the FCC chairman. In short, the FCC has an important, but consultative, role when it comes to space debris—at least for U.S. government agencies.

In 2019, NASA updated The United States Government (USG) Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices (ODMSP), originally established in 2001 to address the increase in orbital debris in the near-Earth space environment. These updated standard practices for the feds included preferred disposal options for immediate removal of structures from the near-Earth space environment, a low-risk geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) transfer disposal option, a long-term reentry option, and improved move-away-and-stay-away storage options in medium Earth orbit (MEO) and above GEO.

But when it comes to commercial use of space, the FCC holds the keys to the kingdom in terms of licensing. Even so, generally speaking, agencies coordinate across the aisle when creating policies that could impact each other. Imagine the surprise when in August the FCC announced a proceeding on Space Innovation; Facilitating Capabilities for In-space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (ISAM).” As defined in this Notice of Inquiry (NOI), the FCC defines missions in its purview as those “which can include satellite refueling, inspecting and repairing in-orbit spacecraft, capturing and removing debris (emphasis added), and transforming materials through manufacturing while in space.”

Playing Nice in the Space Box

An FCC NOI is a way to ask the public to comment on specific questions about an issue to help determine whether further action is warranted. NOIs are the precursor to the agency’s Notice of Public Rulemaking (NPRM).

In this most recent NOI, the FCC specifically seeks comment on “space safety issues that may be implicated by ISAM activities, including orbital debris considerations.”

This is not the commission’s first foray into space debris regulation. It has been reviewing the orbital debris mitigation plans of non-Federal satellites and systems for more than 20 years as part of its licensing and grants for space systems. The commission asserts its authority to regulate orbital debris derives from the Communications Act of 1934, as amended, which provides this authority to license radio frequency uses by satellites.

In 2000, for example, it adopted rules requiring disclosure of plans to mitigate orbital debris for licensees in the 2 GHz mobile-satellite service. Those were the basis for rules applicable to all services that were adopted shortly thereafter (Establishment of Policies and Service Rules for Mobile Satellite Service in the 2 GHz Band, Report and Order, 15 FCC Rcd 16127, 16187-88, paras. 135-138). In 2004, it adopted a comprehensive set of rules on orbital debris mitigation (2004 Orbital Debris Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 11575, para. 14).

Just two years ago, it held an orbital debris proceeding, Mitigation of Orbital Debris in the New Space Age. It sought public comment on a variety of areas for rule updates, including an “active debris removal” as a debris mitigation strategy for planned proximity operations. While it concluded more detailed regulations would be premature, the resultant report nevertheless updated the commission’s satellite rules on orbital debris mitigation for the first time in more than 15 years.

The 2020 FCC rule changes included “requiring that satellite applicants assign numerical values to collision risk, probability of successful post-mission disposal, and casualty risk associated with those satellites that will re-enter earth’s atmosphere.” Among other things, the rule changes also levied new disclosure requirements on satellite applicants related to protecting inhabitable spacecraft, maneuverability, use of deployment devices, release of persistent liquids, proximity operations, trackability and identification, and information sharing for situational awareness.

And yet, others in the interagency balk at what some have referred to as the FCC’s continued stretching of its legal limits. The 2020 rule changes apparently stirred up considerable debate and controversy. Despite objections from the Department of Defense and other government agencies, the FCC pressed ahead.

PNT Industry Impacts?

Fast forward to today. Comments on the FCC’s latest space-based regs focused on ISAM issues are due 45 days following publication in the Federal Register (August 5). Here is the list of topics for which the commission seeks comment. (Note the commission includes space debris as part of ISAM for purposes of this drill):

Spectrum Needs and Relevant Allocation:

The variety of radiofrequency communications links that could be involved in ISAM missions.

Licensing Processes in General: Any updates or modifications to the commission’s licensing rules and processes that would facilitate ISAM capabilities.

Satellite Servicing Missions: Any additional licensing considerations unique to satellite servicing missions including servicing missions consisting of multiple spacecraft.

Assembly, Manufacturing and Other Activities: Any special considerations in licensing of assembly and manufacturing missions.

International Considerations: Whether and how to take into account that ISAM missions also raise the possibility of interactions between operators under the jurisdiction of multiple nations in the commission’s licensing process.

Orbital Debris Mitigation: The implications of updated practices and approaches to stored energy and potential byproducts from in-space assembly.

Orbital Debris Remediation: Whether and how the commission should consider active debris removal as part of an operator’s orbital debris strategy.

Activities Beyond Earth’s Orbit: Any updates to the commission’s rules that might facilitate licensing ISAM missions beyond Earth’s orbit, including missions to the Moon and asteroids.

Encouraging Innovation and Investments in ISAM: Ways to facilitate development of and competition in ISAM activities, provide a diversity of on-orbit service options and promote innovation and investment in the ISAM field.

Digital Equity and Inclusion: How the topics discussed and any related proposals may promote or inhibit advances in diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility, as well as the scope of the commission’s relevant legal authority.

Insofar as all commercial satellites may be affected by this proposal, the PNT community should engage. Will this latest FCC foray into potential space debris rulemaking protect, or lay waste to, the industry’s chances of reaching the space-high projected valuation of $8,817.3 million by 2031? Only time..and space…will tell.