The long-running fight between the GPS community and Ligado Networks intensified in the final months of 2019, fueled by a draft regulatory order, a flurry of letters and scrutiny of the sale of a high-profile supplier.

The firm now known as Ligado has been trying since the fall of 2010 to win federal approval to use its licensed satellite frequencies to also support a terrestrial broadband service. Its predecessor company, LightSquared, filed bankruptcy in 2012 after failing to secure a go-ahead from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to recast its spectrum use and build roughly 40,000 ground terminals. The signals from those terminals, tests showed, would have overloaded the vast majority of GPS receivers.

The firm reorganized and emerged from bankruptcy in 2015 with a new name and a new plan that, it asserted, would not interfere with GPS. Tests by the Department of Transportation (DOT) mapping the power levels of adjacent-band transmissions that GPS receivers could tolerate still found signals like those proposed by Ligado would cause interference problems. Ligado opposed the DOT tests, insisting that the current yardstick for determining interference is wrong. It has yet to convince regulators or the GPS community and, after nearly a decade, the firm still awaits an FCC ruling.

Inmarsat

The debate made new headlines in the financial press this fall after the controversy delayed approval of a $3.4 billion acquisition of Inmarsat by an investment group led by the private equity firms Apax and Warburg Pincus. LightSquared had arranged early on to pay Inmarsat to clear out of frequencies interlaced with its own, giving LightSquared a more efficient block of spectrum for its planned service expansion. When LightSquared filed for bankruptcy, the value of the deal diminished sharply and with it the valuation of Inmarsat. As the sale neared completion last year, some Inmarsat stakeholders argued that Ligado was poised to win FCC approval and asserted that the price for Inmarsat needed to be raised to reflect higher anticipated payments.

It looks like they had real reason for optimism. According to multiple sources, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai had sent a draft order about Ligado to the Interdepartment Radio Advisory Committee or IRAC, to get its feedback. The IRAC is a body within the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), which manages all federal uses of spectrum. It’s not been possible to determine the contents of that order, though Ligado CEO Doug Smith said in a Dec. 11 interview on the podcast Two Think Minimum that the order would let them proceed. Whatever the details, the existence of a draft order suggested that the FCC was moving closer to a decision on Ligado’s request.

It’s unclear why Pai drafted an order this fall. Ligado has been pushing hard for a decision, and some members of Congress may have raised the issue. The Inmarsat sale also doubtlessly boosted Ligado’s profile. Whatever the cause, Pai’s move did shake things up, though perhaps not in ways Ligado expected.

Letters Finally Surface

When LightSquared went through the process that ultimately froze its plans for a terrestrial network, the last element in the decision-making chain was a series of letters. That process is similar to what has been taking place with regard to the current request by Ligado but with several important differences.

One of the key players on the government side has been the National Space- Based Positioning, Navigation and Timing Advisory Board (the PNTAB). This group, the nation’s leading panel of experts on satellite positioning, navigation and timing (PNT), currently comprises 25 members from industry, academia, and international organizations. Some members are technically focused, others expert on usage and governance. Specialized advisors provide further counsel to the board, and military and government representatives regularly attend its meetings.

In the earlier case of LightSquared, the PNTAB sent a letter directly to the Federal Communication Commission citing test results and asking the FCC to rescind a conditional waiver it had given the firm. To do otherwise, the PNTAB said, would hurt U.S. security, economy and infrastructure.

In the current case of Ligado, the board sent a recommendation against approving Ligado’s request to the National Executive Committee for Space-Based PNT, also known as the PNT EXCOM. The Advisory Board support and does research projects for the EXCOM, an interagency committee is made up of seven federal departments, NASA and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Department of Transportation (DOT) co-chairs the EXCOM and represents the needs of civil users. The other co-chair is the Department of Defense, which speaks for military interests.

Though there have been tussles over the years between the civil and military communities, each benefits from the other’s activities and, in real terms, they have found ways to work things out and cooperate. On issues of interference to GPS they are largely in sync.

The EXCOM is one of the most important voices in the LightSquared/Ligado controversy because its work directly informs other agencies’ decisions. Its member agencies have technical expertise because they provide GPS services and augmentations including, for example, DOT’s Wide Area Augmentation System, which supports air traffic control. The EXCOM was specifically asked by the FCC and the NTIA to have its member agencies do the testing that ultimately led to LightSquared’s plan being put on the back burner.

When the EXCOM submitted its conclusions on LightSquared, it pledged to do additional testing to determine what levels of transmissions could be tolerated by GPS receivers. The result of that pledge was the 2012 DOT GPS Adjacent Band Compatibility Assessment. The results of the Assessment have been used to evaluate the Ligado request and determine that Ligado’s plan would still interfere with GPS receivers.

“With regard to the license modification application of Ligado Networks to the Federal Communications Commission,” the EXCOM wrote in a December 2018 letter to the NTIA, “it is clear that the proposed service would exceed the tolerable power limits necessary to prevent disruption of GPS receivers. Based on the results of the extensive studies the NTIA should recommend to the FCC against approval of the license modification.”

DOD Just Says “No”

The “clear and unambiguous” perspective of the EXCOM opinion was noted in the Nov 18 letter sent to the FCC by Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, whose opinion has probably had the most overall impact. There are, he said, “too

many unknowns and the risks are far too great to federal operations to allow Ligado ‘s proposed system to proceed.”

“All independent and scientifically valid testing and technical data shows the potential for widespread disruption and degradation of GPS services from the proposed Ligado system,” Esper wrote. “This could have a significant negative impact on military operations, both in peacetime and war. I, therefore, strongly oppose this license modification.”

Esper pointed out that, by law, he could not agree to any restriction on the GPS System proposed by the head of a department or agency of the United States outside DOD “that would adversely affect the military potential of GPS.” That language was passed by Congress as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1998 and became law in 1997. Any statute is important but because the FCC is overseen by Congress, and not the executive branch, it may carry more weight than usual. It’s harder to go against mandates set by lawmakers when they are, effectively, your bosses.

Esper also noted two letters sent earlier in 2019 by then-acting DOD Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan to the Secretary of Commerce (of which the NTIA is a part) and Chairman Pai. Shanahan asked the FCC to reject Ligado’s request for a license modification and “not allow the proposed system to be deployed per the PNT EXCOM decision.” Shanahan pointed to the same statutory requirement and noted that he had conferred with both his chief technical officer and chief information officer who agreed with his conclusion. If there were any disagreements within the Department of Defense regarding Ligado, it appears that those disagreements were resolved this summer.

NTIA Steps Up

On December 6, a letter from the NTIA was posted to the FCC’s Ligado-related dockets. The NTIA took a softer tone than the other agencies but still said it could not support Ligado’s request.

“The assessment of the potential impacts of the Ligado proposal has been thorough,” wrote Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information Douglas Kinkoph. “Based on these assessments, federal agencies have significant concerns regarding the impact to their mission, national security, and the U.S. economy. Despite the considerable efforts to find a satisfactory solution, NTIA, on behalf of the executive branch, is unable to recommend the Commission’s approval of the Ligado applications.”

NTIA addressed a key element in Ligado’s argument: that more spectrum is needed, especially the Ligado spectrum in the L band, for important new 5G wireless services to advance. The NTIA pointed out that more than 900 MHz of spectrum was already available for licensed mobile services in the preferred frequency ranges below 6 GHz, and another 1,100 GHz was under study. This is in addition to 11 GHz of spectrum in the high-band frequency ranges.

“As a result, an inability to deploy terrestrial 5G or related services using frequencies involved in the Ligado applications will not hold back the timely deployment of 5G across the United States,” NTIA wrote.

When the NTIA sent its final letter regarding the LightSquared question on February 14, 2012, it was game over. NTIA said LightSquared’s proposed mobile broadband network would impact GPS services and there was no practical way to mitigate the interference. The FCC then put out a press release that same day, saying it would not lift the prohibition on LightSquared, it would vacate the Conditional Waiver Order it had granted the company and it would suspend indefinitely LightSquared’s authority to build ground stations to an extent consistent with the NTIA letter.

Ligado asserts that the changes it’s since made to its signal power and frequency plan have solved its GPS interference issues. As made clear by the letters, however, the agencies using and supplying GPS signals do not agree. In fact, if one tallies up the number of departments and agencies with representatives on the Advisory Board, the PNT EXCOM and NTIA’s IRAC, some 26 government organizations believe that interference from Ligado’s proposed network could harm their operations.

Measuring Interference

Those agencies are mistaken, Ligado insists. The real problem, according to the company, is that yardstick they are using to measure interference is wrong.

Ligado wants to use a definition that defines interference as when a signal causes a receiver to function improperly.

“The FCC has a definition of harmful interference,” said Smith, that it has used for decades and with which it successfully created a booming wireless industry. “If they continue to use their same definition of harmful interference, they will move us forward and I am confident they will move us forward. The only objection to them moving forward is really based on kind of a new concept in interference definition and to me, it is absolutely pushing a new definition of harmful interference. It’s one that would have far-reaching implications across the industry because—and I don’t want to get too much into the weeds on the technology—but it’s a 1 dB change, which is a very subtle change in the noise environment.”

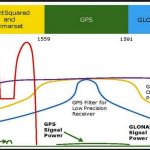

When it comes to satellite navigation, the GPS industry and the FCC have relied on a protection criterion of a 1 dB (1 decibel) change in the carrier-to-noise power density ratio (C/N0), also called the noise floor—but that’s not new.

According to a 2017 background paper written by the Air Force, the 1 dB criterion was used by the FCC in 2003 to develop emission limits for ultrawideband systems, in 2004 for limiting emissions of Low Power Television (LPTV) stations into the GPS band and by the NTIA in 2011 to support the tests it did of LightSquared’s proposal. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has used the 1 dB criterion since the year 2000, according to a table of examples prepared by the Air Force. This approach is used because satellite navigation signals do not work the same way as communication signals.

“Unlike communications systems, which operate above the noise floor— that is, the level of noise occurring naturally at a receiver before a new signal is introduced —spread spectrum GPS signals are below the thermal noise floor when they are received,” wrote the GPS Innovation Alliance in a Dec 20 FCC filing. “The cumulative effects of interference can easily increase the noise floor and degrade GPS performance. Even a small increase in the noise floor may affect a GPS signal’s accuracy, integrity, continuity, or availability in unexpected or dramatic ways. Each of these parameters can be degraded by varying amounts by interference. Monitoring changes in a GNSS receiver’s C/N0 provides a quantifiable and empirical measure of receiver performance that directly influences all four of these parameters.”

“Not only does use of C/N0 have great utility as an objective measure,” stated the Alliance,”but a particular metric—a 1 dB decrease in C/N0—has become a long-utilized and well-recognized interference indicator in the GNSS industry because of its reliability as a comprehensive metric.”

Next Steps

The most important phrase in the NTIA letter may be “on behalf of the

executive branch.” That unusual wording, which was used twice, suggests the White House weighed in on the determination.

Is that possible? It certainly could have been raised as an issue at the highest levels. The executive secretary of the National Space Council is Scott Pace, who is very knowledgeable about both GPS and the LightSquared/ Ligado proposals. The vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is Gen. John Hyten, who has extensive experience in DOD space programs. He told lawmakers in 2016 that the Air Force had not changed its mind about opposing the firm’s proposal.

“I don’t think that we should infringe on the GPS spectrum,” he said. “That’s a critical capability not just for the military security of the nation but for the entire economic well being of this nation. We can’t allow that to happen.”

Though it was not possible to determine by press time if the White House did weigh in on the matter, such phraseology was not used in the NTIA letter regarding LightSquared, nor would it have been. The Obama Administration was pushing for more broadband and favored the firm’s proposal. Even if the White House did not play a role in NTIA’s determination on Ligado, a lot of agencies certainly did.

If the current process remains aligned with how the LightSquared process played out, then the FCC should now take some sort of action. Ligado is urging the FCC to ignore the negative feedback on its proposal, suggesting that failure to do so would bring the FCC’s independence into question.

But the FCC need not decide one way or another. It could, for example, ask for more testing, perhaps to address the matter of how to measure interference. The Inmarsat deal has gone through and there is no other obvious forcing function to make Pai and his fellow commissioners take action. Ligado filed a request for a decision under Section 7 of the Communications Act, but the rules for applying that section are only now being developed.

Back when LightSquared’s request was set aside there were a number of lawsuits filed against members of the GPS community and the federal government. That last suit was withdrawn without prejudice and could be revived—a possibility more likely to further stall action than inspire it.

Many people draw up a list of action items at the beginning of the year. Ligado’s situation consists more of a list of no-action items. Unless the firm changes its approach, or some other outside force energizes the FCC, the entire issue could remain mired for the foreseeable future.