As a child, I frequently traveled with our family to San Francisco where, sooner or later, we usually visited the shops in Chinatown. On one trip there I discovered a delightful novelty: wooden puzzle boxes with a series of sliding panels that needed to be pushed in just the right order to reveal a small drawer inside.

These boxes were like a kind of Rubik’s cube or sudoku, only less mathematical and more appealing to a 10-year-old’s sensibilities.

As a child, I frequently traveled with our family to San Francisco where, sooner or later, we usually visited the shops in Chinatown. On one trip there I discovered a delightful novelty: wooden puzzle boxes with a series of sliding panels that needed to be pushed in just the right order to reveal a small drawer inside.

These boxes were like a kind of Rubik’s cube or sudoku, only less mathematical and more appealing to a 10-year-old’s sensibilities.

My memory of these puzzle boxes was jogged by the recent pronouncements of the People’s Republic of China about its intention to build a full-fledged GNSS called Compass (also referred to as Beidou, after an experimental constellation of satellites now in place).

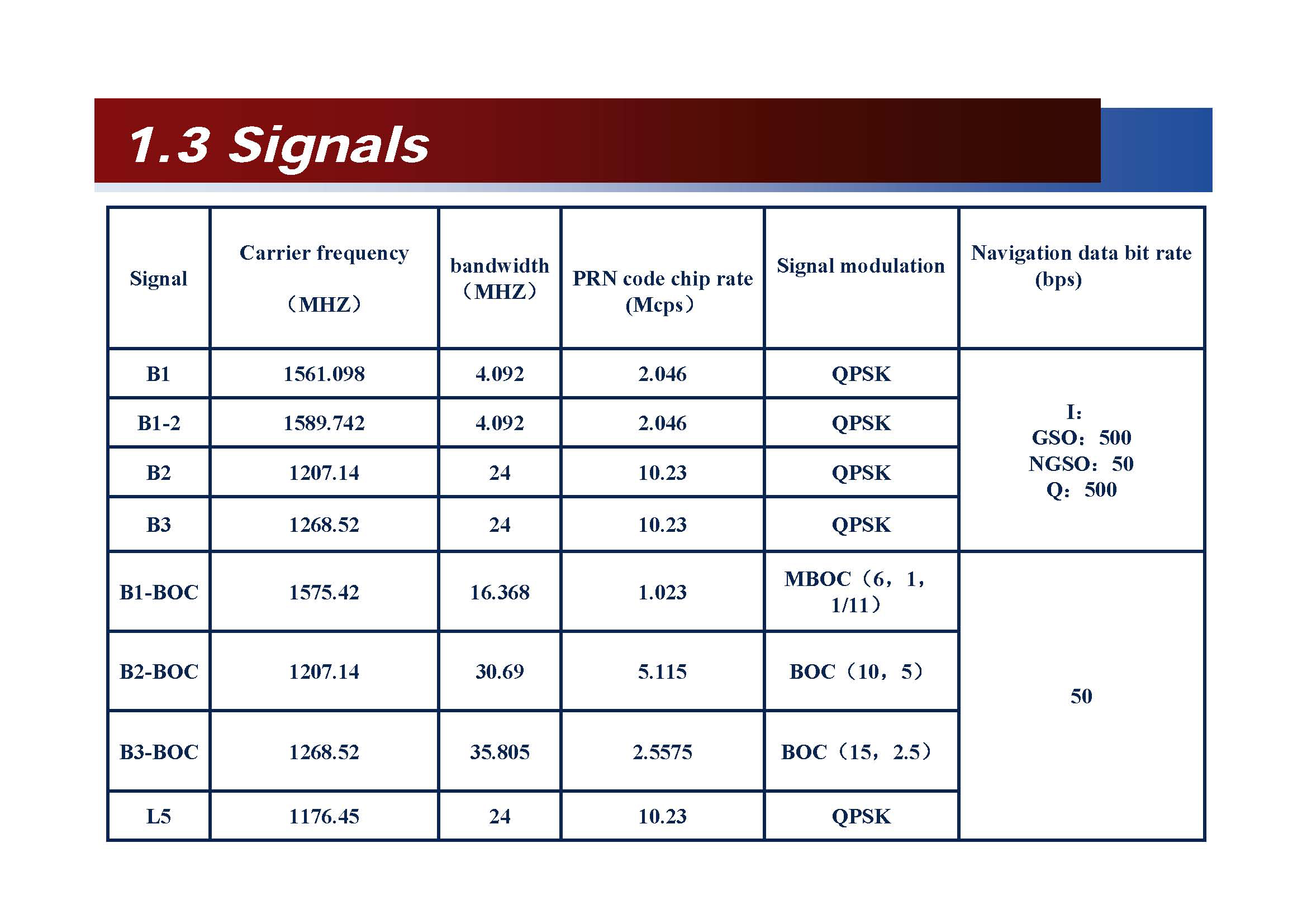

Brief explanations issued through the national news agency, Xinhua, were rather sketchy on details for the civil/commercial service to be provided by the 35-satellite system, along with a secure military service. Sources of the information also were characterized vaguely. And no additional public announcements have yet followed that initial report nor, apparently, have substantive discussions taken place with other leading GNSS nations.

Reactions and speculation from officials in other nations have been much more in evidence than further elaboration by China. How would a signal transmitted over a portion of the GPS M-code and Galileo Publicly Regulated Service (PRS) affect the security applications associated with the latter? What are the implications for China’s involvement in the Galileo program, in which it made a €200-million investment under a 2003 agreement with the European Union? Is this a trial balloon, political pressure, or the real deal?

The paucity of public discussion by Chinese officials leaves Compass as something of a puzzle. Certainly, the GNSS community has become accustomed to extensive public deliberations — and private intergovernmental conversations — on the subject of Galileo. GPS, too, in an era of presidential directives, dual-use, and modernization has generated a multi-sided dialog. Even Russia has become much more steadfast in its revelations about GLONASS.

But this is a much more suitable mode of operation for mature systems already in place or a would-be system such as Galileo with a large cast of characters who have to be talked into taking part. For a single nation shaping an important part of its future, keeping one’s own counsel until the practical requirements of a decision have been put in place seems quite understandable.

The scale of a nation’s endeavors tells us a lot about the scope of its ambitions. If Compass/Beidou remains a national or regional system, its significance and the intentions behind it are similarly limited. If Compass becomes a global navigation satellite system, we can assume that its sponsor’s ambitions have a similar scope. If I were a betting man, I’d bet on the latter outcome.

I believe that the political and economic logic driving China with Compass is at least as great as that for Europe regarding Galileo. For reasons of sovereignty and security, major world powers cannot allow control over a critical infrastructure — and technological and economic engine — such as GNSS to reside with others. Certainly the United States believes this about GPS, and Russia’s President Putin has similarly assessed GLONASS in throwing his support behind rebuilding and modernizing that system.

A crucial question, of course, is how open China is to pursuing a common, compatible, and perhaps interoperable future with other GNSS operators. One good sign: After initial hesitance, China quite enthusiastically joined the United Nations–fostered International Committee on GNSS (ICG) at its founding meeting late last year. There the rising Asian power will almost certainly become a member of the ICG Providers Forum, which could provide a locus for useful discussions, if not actual agreements, for creating a compatible and eventually interoperable GNSS system of systems.

Ultimately, as in other areas of endeavor, actions will speak louder than words. And when Compass arrives, in whatever form, it will say much about this Chinese puzzle.