A new U.S. appellate court decision could bring the issue of warrantless tracking of suspects using GPS and other positioning data derived from mobile phones back before the Supreme Court.

And if the case — United States of America v. Melvin Skinner — is appealed to and accepted for review by the “Supremes,” they would probably have an opportunity to more directly address the question of whether U.S. citizens have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in their personal location information garnered surreptitiously from GPS-enabled cell phones by police.

A new U.S. appellate court decision could bring the issue of warrantless tracking of suspects using GPS and other positioning data derived from mobile phones back before the Supreme Court.

And if the case — United States of America v. Melvin Skinner — is appealed to and accepted for review by the “Supremes,” they would probably have an opportunity to more directly address the question of whether U.S. citizens have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in their personal location information garnered surreptitiously from GPS-enabled cell phones by police.

In a ruling issued this week (August 14, 2012), three judges from the U.S. Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit (Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee), upheld Skinner’s conviction and sentencing for a 2006 case involving interstate transport of marijuana.

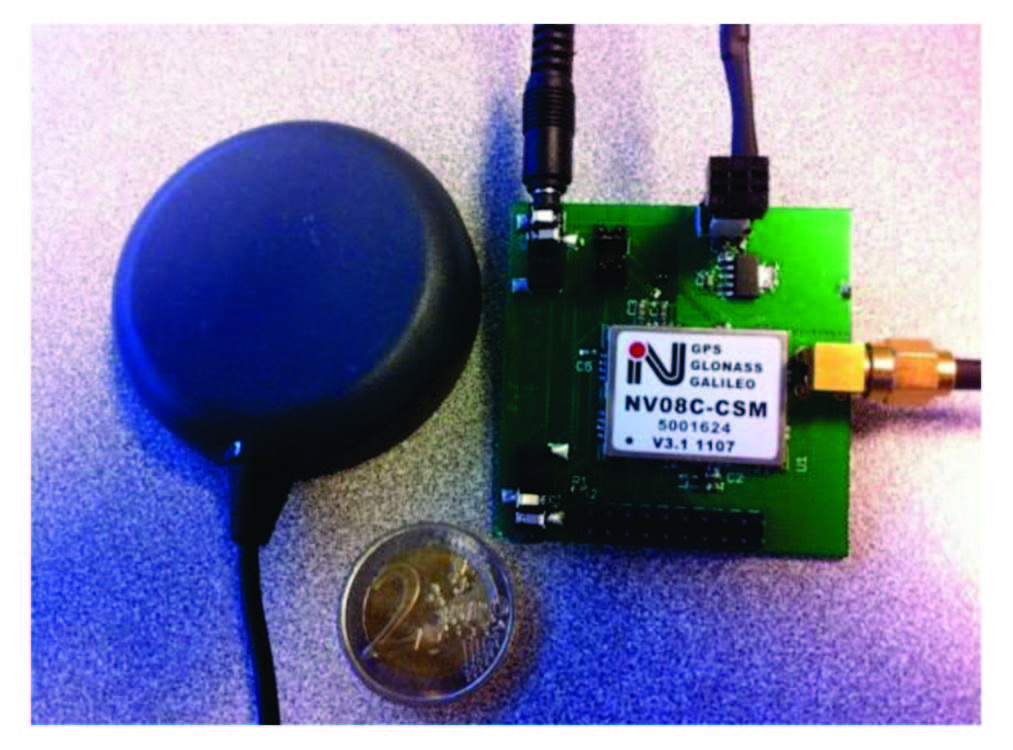

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) tracked and intercepted Skinner at a Texas truck stop using cell site information, GPS real-time location, and “ping” data obtained from a phone company from Skinner’s pay-as-you-go mobile phone.

DEA officers had obtained a magistrate’s order allowing them access to the data, but not a warrant issued on probably cause. Consequently, Skinner appealed his conviction arguing that it was based on an illegal search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Judge John M. Rogers, delivered opinion, Eric L. Clay concurred. Judge Bernice B. Donald concurred in part of the opinion (but disagreed with Rogers’ analysis of the warrantless tracking issue) and in the final judgment.

The appellate court’s decision distinguished Skinner’s case from the recent Supreme Court decision in United States v. Antoine Jones. In that case, the court overturned a warrantless search that depended on GPS positioning data from a device placed on the suspect’s vehicle because of “trespassory nature of the police action,” the Sixth Circuit judges said.

In Skinner’s case, the information was gained directly from Skinner’s phone, the number for which — but not Skinner’s identity or location — had been gained from wiretaps of another suspect in the drug investigation.

Rogers and Clay opined that because “authorities tracked a known number that was voluntarily used while traveling on public thoroughfares, Skinner did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the GPS data and location of his cell phone.” Moreover, any “innocent” private citizen “would similarly lack a reasonable expectation of privacy in the inherent external locatability of a tool that he or she bought.”

In effect, the two judges’ argued that gathering Skinner’s location data from the phone company represented surveillance, not a search.

Judge Donald, however, wrote that she did “not agree that Skinner lacked a reasonable expectation of privacy in the GPS data emitted from his cellular phone. In my view, acquisition of this information constitutes a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment, and, consequently, the officers were required to either obtain a warrant supported by probable cause or establish the applicability of an exception to the warrant requirement.”

Noting previous decisions supporting authorities’ use of electronic surveillance to aid surveillance already initiated, Donald said that in Skinner’s case, “police had not and could not establish visual contact with Skinner without utilizing electronic surveillance because they had not yet identified the target of their search. Authorities did not know the identity of their suspect, the specific make and model of the vehicle he would be driving, or the particular route by which he would be traveling. Moreover, officers could not have divined any of this information without the GPS data emitted from Skinner’s phone. . . .”

Although she ultimately agreed that the DEA officers had “probable cause” to stop and search Skinner, Donald argued that the legal issue requiring a search warrant turns on whether a person has a “constitutionally protected reasonable expectation of privacy” as defined in a 1967 Supreme Court decision, Katz v. United States. That, in turn, depends on a two-part test, she said, “First, has the individual manifested a subjective expectation of privacy in the object of the challenged search? Second, is society willing to recognize that expectation as reasonable?”

Donald concluded, “Skinner’s use of the phone arguably manifests his subjective expectation of privacy in his GPS location information,” adding that the “critical question, then, is whether society is prepared to recognize Skinner’s expectation of privacy as legitimate.”

This was the same issue raised by five of the justices in the Antoine Jones decision, who agreed that the case could have been decided on the basis of Katz v. United States, and the “legitimate expectation of privacy.” However, in that case, one of the judges joined the other four justices led by Antonin Scalia in agreeing that the decision could be based on the narrower trespass issue.

Nonetheless, given that Katz-based head count, the U.S. Supreme Court appears likely to ultimately take up a case such as that of Melvin Skinner to address whether U.S. citizens have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their movements and location based on GNSS positioning and mobile communications.