A General Accountability Office (GAO) report on “GPS Disruptions” issued today (November 6, 2013) concludes that the Department of Transportation (DoT) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) need to improve their efforts to assess the associated risks and mitigate them.

The report comes nearly nine years after a National Security Policy Directive (NSPD-39) on U.S. Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Policy directed the agencies to develop a plan for detecting and mitigating GPS interference and develop a backup PNT capability.

A General Accountability Office (GAO) report on “GPS Disruptions” issued today (November 6, 2013) concludes that the Department of Transportation (DoT) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) need to improve their efforts to assess the associated risks and mitigate them.

The report comes nearly nine years after a National Security Policy Directive (NSPD-39) on U.S. Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Policy directed the agencies to develop a plan for detecting and mitigating GPS interference and develop a backup PNT capability.

Signed by two GAO officials, Mark Goldstein director of physical infrastructure issues, and Joseph Kirschbaum, acting director for homeland security and Justice Issues, the report concludes, “[D]ue to resource constraints and other reasons, the agencies have made limited progress in meeting the directive, and many tasks remain incomplete, including identifying GPS backup requirements and determining suitability of backup capabilities,” later adding that “overall, the requirements of NSPD-39 remain unfulfilled.”

Prepared over the past year in response to a request from chairmen of the U.S. Senate and House committees on homeland security, the report examined the following issues:

· the extent to which DHS has assessed the risks of GPS disruptions and their potential effects on the nation’s critical infrastructure

· the extent to which DoT and DHS have planned or developed backup capabilities or other strategies to mitigate the effects of GPS disruptions

· what strategies, if any, selected critical infrastructure sectors employ to mitigate the effects of GPS disruptions, and any remaining challenges they face.

While noting the resource constraints of the agencies, the GAO recommendations dwelled mostly on methodological and management issues associated with risks and mitigation of GPS disruption. For example, agency investigators noted that DHS had published a GPS National Risk Estimate (NRE) in 2012, but criticized it as “incomplete” because it only considered 4 out of 16 critical infrastructure sectors and has not been widely used by DHS or other agencies to inform executive-level decisions.

Moreover, according to the GAO, the NRE was not consistent with a National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) drafted by DHS in 2006 and updated in 2009, which identified GPS as a system that supports or enables crucial functions in critical infrastructure sectors.

The GAO report states that DHS officials “acknowledged the data and methodological limitations of the NRE, but stated that they have no plans to conduct another NRE on GPS because of resource constraints.”

The GAO investigators also suggested that the agencies’ efforts have been hampered by a lack of effective collaboration. “In particular, DoT and DHS have not clearly defined their respective roles, responsibilities, and authorities or what outcomes would satisfy the presidential directive.”

GAO said that DHS has completed few of the GPS interference detection and mitigation (IDM) activities mandated by NSPD-39. Noting that DHS had established an incident portal “to serve as a central repository for all agencies reporting incidents of GPS interference and developed draft interagency procedures and a common format for reporting incidents.” However, the report continues, “The incident portal is hosted by FAA, but due to its security policy, other agencies are not able to access the portal.”

Identifying GPS backup-system requirements and determining suitability of backup capabilities also remain incomplete, the GAO said, observing that DHS officials cited a variety of reasons why they have not made additional progress, such as insufficient staffing and budget constraints. DHS’s PNT Program Management Office (PMO), which leads the agency’s IDM efforts, has three full-time staff members, one of whom is currently working in another component of DHS.

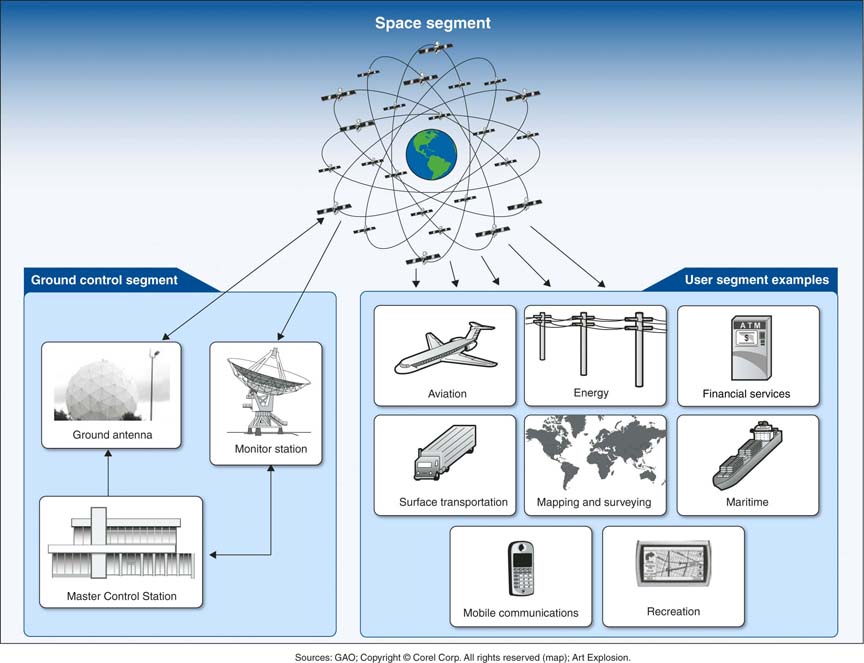

An additional problem, the GAO said, is that GPS program management is separated from infrastructure protection management within DHS. The agency’s National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) leads and manages efforts to protect the nation’s critical infrastructure sectors, but the PNT PMO leads DHS’s IDM efforts, falls under the Office of the Chief Information Officer. (See accompanying figure.)

DHS officials told GAO investigators that each individual critical infrastructure sector might need to be responsible for providing its own GPS backup solutions. In contrast, DoT officials said that individual solutions for every sector would be “redundant and inefficient” and that DoT “does not desire a sector-based architecture for GPS backup capabilities.”

The GAO officials added that DHS “told us that a single, domestic backup to GPS is not needed,” while DoT officials argued that “a single backup solution fulfilling all users’ needs would not be practical.”

Nevertheless, the DoT officials stated that the U.S. Coast Guard’s decommissioning of LORAN-C “was a loss for the robustness of GPS backup capabilities,” especially given that both DoT and DHS had supported the upgrading of LORAN-C to enhanced LORAN (eLORAN) as a national GPS backup.

To ensure that the increasing risks of GPS disruptions to the nation’s critical infrastructure are effectively managed, the GAO recommend that the Secretary of Homeland Security take the following two actions:

• Increase the reliability and usefulness of the GPS risk assessment by developing a plan and time frame to collect relevant threat, vulnerability, and consequence data for the various critical infrastructure sectors, and periodically review the readiness of data to conduct a more data-driven risk assessment while ensuring that DHS’s assessment approach is more consistent with the NIPP.

• As part of current critical infrastructure protection planning with SSAs [sector-specific agency] and sector partners, develop and issue a plan and metrics to measure the effectiveness of GPS risk mitigation efforts on critical infrastructure resiliency.

To improve collaboration and address uncertainties in fulfilling the NSPD-39 backup-capabilities requirement, we recommend that the Secretaries of Transportation and Homeland Security take the following action:

• Establish a formal, written agreement that details how the agencies plan to address their shared responsibility. This agreement should address uncertainties, including clarifying and defining DOT’s and DHS’s respective roles, responsibilities, and authorities; establishing clear, agreed-upon outcomes; establishing how the agencies will monitor and report on progress toward those outcomes; and setting forth the agencies’ plans for examining relevant issues, such as the roles of SSAs and industry, how NSPD-39 fits into the NIPP risk management framework, whether an update to the NSPD-39 is needed, or other issues as deemed necessary by the agencies.