A recently announced deal between the United States and the United Kingdom to revoke the UK’s surprise patents on a key GPS technology has a glaring omission: Intentionally left out of the agreement are patents on the European Union’s version of the technology, a signal structure important to enabling Europe’s Galileo system to work seamlessly with America’s GPS constellation.

A recently announced deal between the United States and the United Kingdom to revoke the UK’s surprise patents on a key GPS technology has a glaring omission: Intentionally left out of the agreement are patents on the European Union’s version of the technology, a signal structure important to enabling Europe’s Galileo system to work seamlessly with America’s GPS constellation.

Most navigation receivers tap as many signals as possible from the various satellite constellations. Unless a deal is reached between the UK and the EU, manufacturers everywhere, including in the U.S., could still be facing royalty payments for receivers utilizing the Galileo E1 signal.

The GPS and Galileo signal structures in the patents were developed jointly by the U.S and EU through the Galileo Signal Task Force of the European Commission. The group was created as part of the agreement on the promotion, provision, and use of Galileo and GPS satellite-based navigation systems and related applications — a landmark 2004 accord formalizing cooperation on satellite navigation between the United States and more than two dozen European countries, including the United Kingdom.

In the joint US/UK statement issued January 17 the UK government said it would dedicate “all government held patents and patent applications relating to U.S. GPS civil signal designs and their broadcast from GPS and other global navigation satellite systems to the public domain.” So, that covered the use of the new GPS signal designs by both GPS and other GNSS operators, but not European variants on the common signal design.

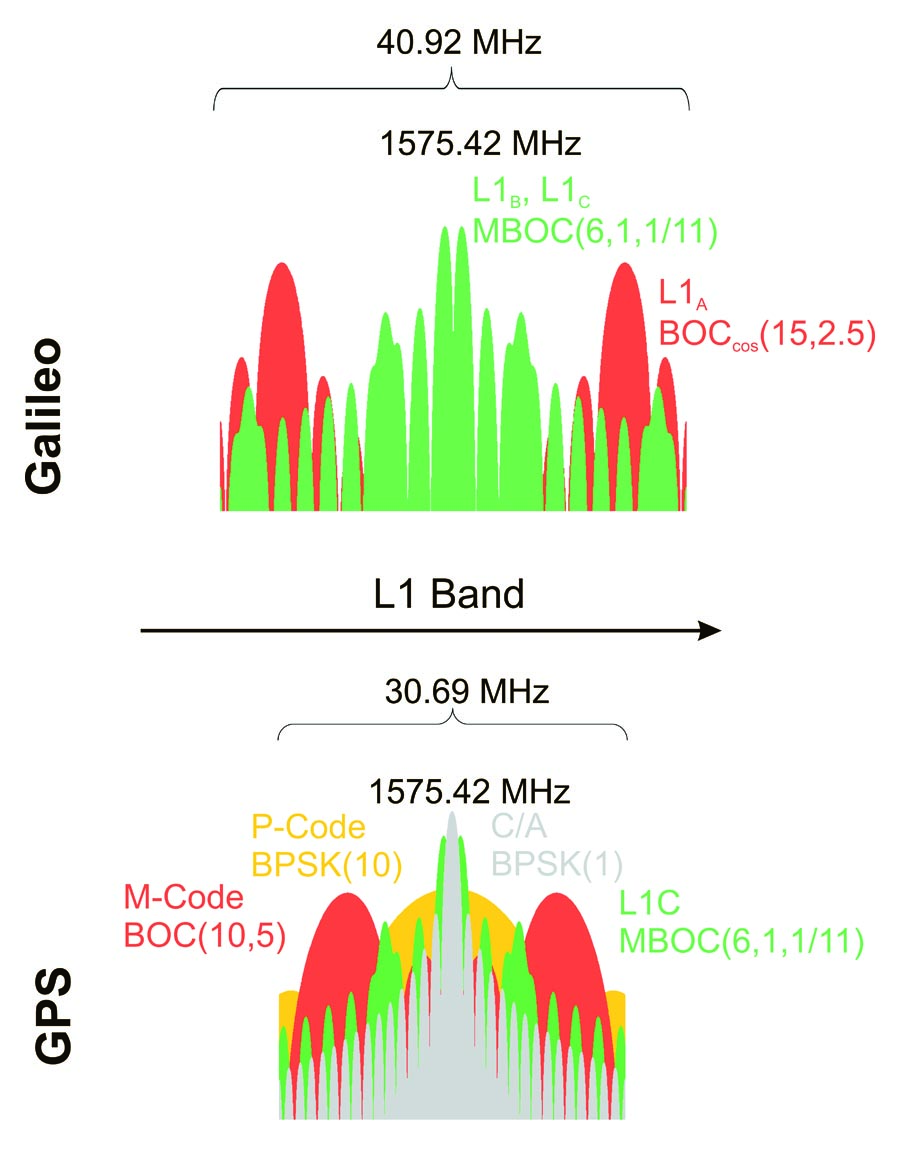

Alhough they are completely compatible and essentially interoperable, the two signal structures are slightly different. GPS will use a Time Multiplexing Binary Offset Carrier or TMBOC signal structure for the modernized L1 civil signal (L1C) being introduced on the new GPS III satellites set for launch starting in 2015. The EU will use a CBOC or Composite Binary Offset Carrier signal structure for its upcoming E1 signal.

A number of U.S. agencies wanted to include the Galileo signal in the patent agreement because they were looking at combination GPS/Galileo receivers, said one U.S. source familiar with the negotiations. But the United States was asked to take a “hands off” position on that point. Leaving the Galileo signals out of the deal was a compromise with the United Kingdom.

“The only thing that we basically agreed on is that we would stay out of their direct negotiations with the European Commission and the Galileo program with respect to that second family of patents — the CBOC family,” confirmed a U.S. official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

One European expert following the issue, who asked not to be named, said the omission of the EU in the announced deal was “quite surprising” and a cause for concern. It would have been “more consistent with the aim of the Cooperation Agreement,” this expert said, to include Galileo to ensure “compatibility and interoperability between the two systems.”

“The EU must have the same interest as the U.S.,” said the expert in an emailed comment, “avoiding any claims which could make the system, services, receivers etc. more expensive — creating problems with interoperability and compatibility, creating problems on [the] diplomatic level, increasing the overall programme costs, hindering market development etc. [The EU] should thus have intervened as strongly as the U.S. and should have the same goal/position versus the UK, . . . that all patents should be made public.”

The European expert noted that the UK/EU discussions were taking place in the context of broader talks on the budget for the European Union in general and more specifically for Galileo and other EU space projects.

A source familiar with the U.S./UK deal suggested that the UK might be seeking some sort of financial deal with the EU over the patents.

“We would like to see a situation where end-users and manufacturers aren’t forced to pay fees and royalties,” said the U.S. official. “That’s it. . . . If there is some exchange of money or something else between the UK and the EU that’s their business and that is all we agreed to do — is stay out of that business.”

The patents first came to light in 2011 when Ploughshare Innovations, a wholly owned subsidiary of the research and development division of the British Ministry of Defense, began asking U.S. receiver manufacturers for royalties and —in at least one case, a source said at the time — a cut of revenue.

The patents were filed for by the British Secretary of Defence for the U.K.’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), although the inventors listed on the patents were Tony Pratt and John Owen. Both men were on the Galileo Signal Task Force — and questions arose immediately as to whether the technology had actually been submitted to the group by others and then patented by the UK.

At least one well-placed source said an email trail clearly indicated that U.S. engineers were the true originators of the patented innovation, but it appears that the matter will not be raised again. Although some on the U.S. side wanted to take the matter to court to get what happened into the public record, the final deal avoided a court fight and any mention of blame or error.

“That we did not say that [the UK] trampled on our IP— that they took our intellectual property and patented it. That was something that they wanted,” said a source familiar with the deal.

“The bottom line is that [who invented it] doesn’t matter any more,” said the U.S. official. “It is in the public domain.”

U.S. sources said that DSTL and Ploughshare initially resisted agreeing to a deal. When upper levels of the British government became aware of the situation, however, elements of an agreement began to quickly coalesce.

Although the U.S. official declined to comment on any sticky points in the talks, they did add that “when the right levels of the UK government became aware of this issue, they made a very wise decision.”