While an independent report from NASEM has validated some NTIA GPS interference claims, no real mitigation is in in sight.

A Congressionally-mandated independent technical review from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) recently found that Ligado Networks’ low-power terrestrial mobile satellite services (MSS) in the L-band may not harm most commercial uses but will, in fact, interfere with GPS for high precision receivers, Department of Defense (DoD) missions and downlinks from Iridium satellite terminals.

To pile on, mitigation measures may not be practical “at operationally relevant time scales or at reasonable cost.” The NASEM report also suggested FCC tighten up its receiver standards and spectrum-related proceedings in the future. Let’s review the bidding.

How Did We Get Here?

April marked the 2-year anniversary of the FCC granting the conditional and modified license (FCC 20-48) for Ligado’s national MSS network. But the back-and-forth on concerns about near-band interference goes back more than 20 years. The project’s history, dotted with stops and starts (including during the bankruptcy of Ligado’s precursor company LightSquared) and contradictory testing results has created a lengthy public record rife with controversy and emotion.

In the one corner, stands Ligado. Its vision is “to modernize American infrastructure by connecting the Industrial Internet of Things” with state-of-the-art satellite technology and plans to deploy Custom Private Networks to provide the cutting edge technology needed for the future of 5G. Ligado believes interference claims have been overblown and that potential interference can be mitigated, and stands ready to discuss how to do that.

On the other side of the ring, we have the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) on behalf of the executive branch, industry, trade associations and Ligado opposition groups such as the Keep GPS Working Coalition. This crowd remains adamant that Ligado’s L-spectrum block will pose a threat to the viability of civil and military GPS receivers across the country.

In 2020, when the FCC unanimously and conditionally approved Ligado’s amended license request, these opponents pled with the FCC to both halt the creation of Ligado’s network and reconsider its decision. In January 2021, the FCC struck down the request to halt Ligado’s progress. However, it still hasn’t ruled on the reconsideration issue.

Much of the debate around the propriety of Ligado’s license is on whether the 1 dB C/N0 interference metric proposed by the feds, but not embraced by the FCC in its ruling for Ligado, is the correct standard to use.

In the midst of this bout, Congress jumped in to referee and ultimately leveraged its power of the purse. In Section 1661 of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress stopped the DoD from using government funds for technical or information exchanges with Ligado or to retrofit affected equipment, required the Department to submit estimates of reimbursable costs for any retrofit, and directed the DoD to charter an independent NASEM review.

At the heart of this review, NASEM was to compare “the two different approaches used for evaluation of potential harmful interference” and submit a report. The two other elements of NASEM’s task included assessing the: (1) likelihood that the authorized Ligado service will create harmful interference to GPS, MSS and other commercial or DoD services and operations and (2) feasibility, practicality and effectiveness of the measures in the FCC order to mitigate harmful interference effects on DoD devices, operations and activities.

NASEM got a late start and missed its 270-day deadline. However, its effort can be characterized as nothing short of herculean. The group, led by Committee Chair Michael McQuade, Ph.D., strategic advisor to the president at Carnegie Mellon University, listened to dozens of hours of live testimony and reviewed almost 100 documents over several months before rendering the following conclusions on the three tasks:

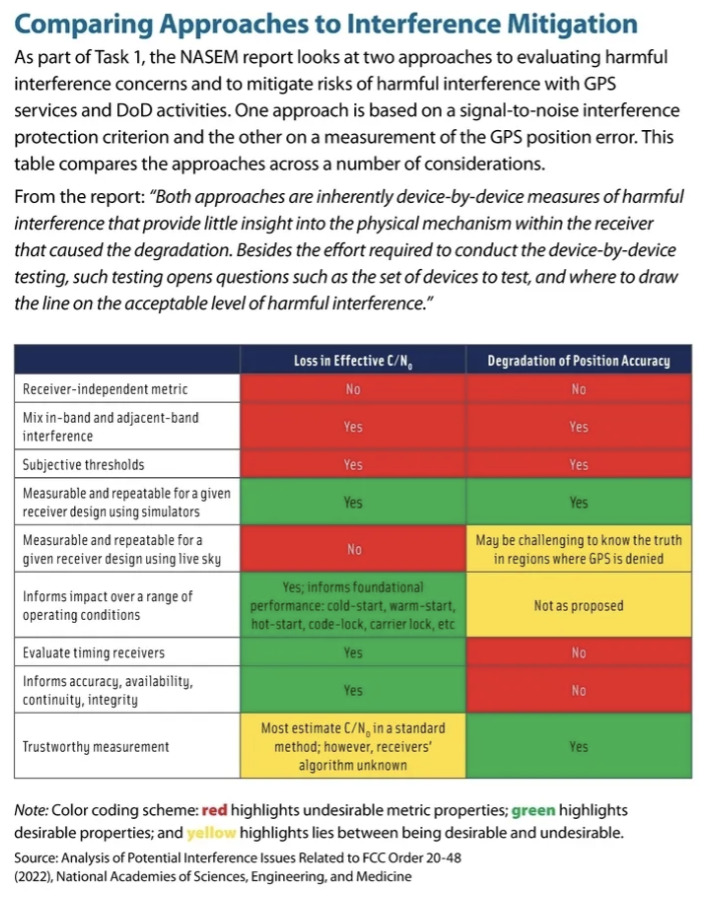

TASK 1: Approaches to Evaluating Harmful Interference Concerns. The committee determined that neither of the NTIA or Ligado approaches to evaluating harmful interference concerns effectively mitigates the risk of harmful interference.

While both approaches have a role to play in such evaluations, and the NTIA signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) approach may be a bit better than Ligado’s position measurement approach, each has serious flaws.

The SNR approach, the report found, is inflexible and, in some cases, has an overly conservative emission limit because “no single value for signal-to-noise degradation determines when the various types of possible harm to receiver performance will become significant.” The measurement approach depends on a test sampling approach too narrow to apply to the many and varied uses of the GPS system. The mic drop portion states:

“Ultimately, both proposed approaches are cumbersome, owing to the intensive, device-by-device testing required. They do not provide an engineerable, predictable standard that new entrants can readily use to evaluate impact. As such, these approaches impede progress in making more efficient and effective use of the spectrum.”

TASK 2: Harmful Interference to GPS and Mobile Satellite Services. In Ligado’s favor, the report found that, as authorized by the FCC, most commercially produced general navigation, timing, cellular or certified aviation GPS receivers will not experience significant harmful interference from Ligado emissions.

That said, critical high-precision receivers remain the most vulnerable to significant harmful interference from Ligado operations, as do downlinks for Iridium terminals within up to 732 meters (“a significant range”) of Ligado user terminals operating in the UL1 band.

The report discussed DoD systems and missions in a non-public and classified annex, but noted the DoD and agency partner testing demonstrated unacceptable harmful interference to national security missions.

The fix? The report found current state-of-the-art technology could be used to build a receiver robust enough to peacefully coexist with Ligado signals and achieve “good performance” for any GPS application. But, see the conclusions on task 3…

TASK 3: Feasibility, Practicality and Effectiveness of Mitigation Measures in the FCC Order. The FCC’s proposed mitigation measures included, among other things, exclusion zones for Ligado emitters, replacing antennas, filters or full receivers, enabling a “kill switch” to turn off Ligado emitters in some areas and other negotiated mitigations between Ligado and the affected parties.

The report found that while the proposed mitigations may be effective for DoD and national security end-users, where these are immediately available, such mitigation is neither satisfactory nor practical without both extensive dialogue among the impacted parties combined with long and expensive operational test certifications. On the commercial side (even commercial tech that DoD employs), “mitigation may not be practical at operationally relevant time scales or at reasonable cost.”

So, Where Are We?

The bottom line: no perfect interference standard exists; most commercial GPS will be OK but really important national security and satellite tech will experience inference from the Ligado emitter; state-of-the-art tech could help mitigate GPS interference, but would require collaboration between the parties, would take a really long time and would be expensive.

And yet both sides touted the report as a win.

Ligado professed in a statement, “The NAS(EM) found what the nation’s experts at the FCC already determined: A small percentage of very old and poorly designed GPS devices may require upgrading. Ligado, in tandem with the FCC, established a program two years ago to upgrade or replace federal equipment, and we remain ready to help any agency that comes forward with outdated devices. So far, none have.”

Not surprisingly, the DoD took a different view of the report:

“The NASEM study confirms that Ligado’s system will interfere with DoD GPS receivers, which include high-precision GPS receivers. The study also confirms that Iridium satellite communications will experience harmful interference caused by Ligado user terminals. Further, the study notes that when DoD’s testing approach, which is based on signal-to-noise ratio, is correctly applied, it is the more comprehensive and informative approach to assessing interference. The study also concludes that the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) proposed mitigation and replacement measures are impractical, cost prohibitive, and possibly ineffective.

These conclusions are consistent with DoD’s longstanding view that Ligado’s system will interfere with critical GPS receivers and that it is impractical to mitigate the impact of that interference.”

As both sides chalk the NASEM report up as a validation of their position, much work remains to be done.

Where Do We Go From Here?

For one, the FCC needs to move out—either way—on the pending Petition for Reconsideration. Enough is enough. In the latest move in that arena, on October 13, a host of businesses and associations, jointly requested the FCC to consider the unclassified portion of the NASEM report “to ensure completeness of the record” for the pending petitions for reconsideration.

As we know, however, the FCC has not taken any action on the Ligado proceedings since early last year. The Commission, which exists independent of the White House, remains deadlocked in a 50/50 split and one member short of a full majority. Meanwhile, the Senate continues to stonewall the appointment of Democratic nominee, Gigi Sohn, to the FCC. Sohn’s appointment would seal a Democratic majority. Not surprisingly, Republicans have stiff-armed her nomination, putting off the vote for more than a year now. Sohn would have given Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel the vote needed to pursue rulemakings opposed by the commission’s Republicans.

According to Jennifer Richter, Partner and Head of the communications and information technology practice at Akin Gump, an award-winning global law firm, the Commission does not need to wait. “If Chairwoman Rosenworcel has a majority on any item, that item can pass,” she said. That means the FCC could not only take action on the petition, but also move out on several reasonable suggestions in the NASEM report.

To start, the FCC could update its definition of “harmful interference.” The FCC currently defines it as “interference which endangers the functioning of a radionavigation service or of other safety services or seriously degrades, obstructs, or repeatedly interrupts a radiocommunication service operating in accordance with [the International Telecommunication Union] Radio Regulations.” The committee blamed this non-quantifiable definition of harmful interference for the years long Ligado quagmire, which it says, “has tied up spectrum, as well as untold resources of the participants.”

What could work? In the case of GPS, a harmful interference criterion that accounts for position error effects, acquisition and tracking challenges, and continuity of service potentially based on a maximum limit for degradation of C/N0, possible effects of out-of-band emissions (OOBE) and adjacent-band signals in a designated frequency range for a reasonably well designed receiver to dictate an adjacent-band power mask that the FCC would guarantee going forward for a given period of time.

The FCC might also consider revising design and implementation standards for receivers themselves, in a nuanced way. As the report noted, “One must…distinguish between receiver standards that address operation in the current environment and those that might protect operation in the presence of some future uses that were vastly different in their impact.”

Then there’s the matter of spectrum, and how it should be allocated from a process standpoint. The FCC has no cohesive policy about rights of current users, the impact of equipment lifetime, business models, and similar essential considerations. According to the report, “This must be established outside the pressures of any one spectrum decision” and “current actions supporting the repurposing of spectrum is at best, ad hoc, and certainly does not operate on the same timeline as that which the technology is capable of changing.”

Appearances also matter. The committee suggested all parties might have found the proceedings more palatable had the FCC made independent findings of fact instead of quoting out of the various parties’ filings.

Fairness aside, these issues always boil down to money. But the FCC also has no policies for equipment owner’s rights when it comes to spectrum. The report outlined issues to think about such as: “What is the lifetime for any mitigation responsibility? What is the responsibility for receiver performance? How is any such responsibility addressed administratively?”

Finally, revectoring processes to take a more collaborative, instead of litigious, approach would go a long way to ending “successive cycles of argument.” Steps might include jointly studying and testing the impact of proposed regimes using agreed-upon criteria, experiments and cases. Gone are the days of completely segregated federal and non-federal spectrum.

If the FCC encouraged both communities to have more internal and external coordination and related negotiation, we could all have a higher degree of confidence in the process, our federal agencies and the equitability of spectrum allocation.

Read the NASEM report. You can read the full Ligado report here:

https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26611/chapter/1.