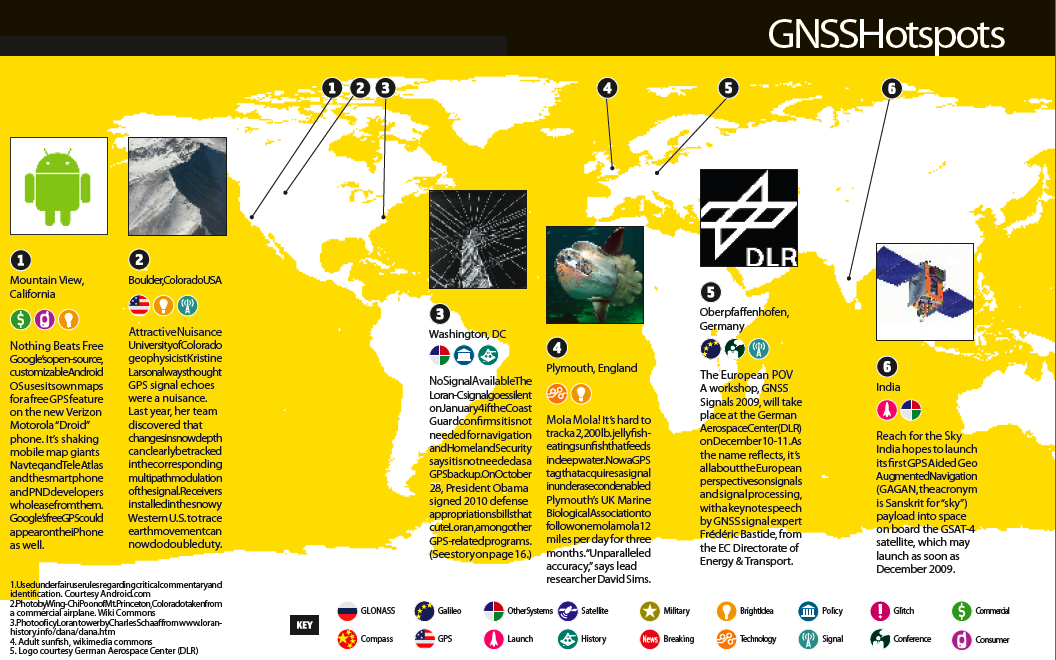

In the world of GNSS we usually think of more as better. More systems, more satellites, more signals — all contribute to greater availability of robust positioning, navigation, and timing.

Certainly that was the mood at the June meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation — GNSS Implementation Team (APEC-GIT) in Seattle, Washington.

In the world of GNSS we usually think of more as better. More systems, more satellites, more signals — all contribute to greater availability of robust positioning, navigation, and timing.

Certainly that was the mood at the June meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation — GNSS Implementation Team (APEC-GIT) in Seattle, Washington.

Everybody was celebrating progress with their systems: the first GPS Block IIF in orbit, another Compass GEO up, GLONASS constellation nearing completion, Europe’s EGNOS approaching certification, more than 100 satellites expected to be in orbit by 2020.

It all sounded good.

That is, until Tim Murphy came along.

Until then, the reports from representatives of the various GNSS and regional augmentation systems were accentuating the positive: better coverage in urban canyons, improved dilution of precision (DOP) metrics, more signals to use for receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM), and so on.

But about 21 slides into his Powerpoint presentation, Murphy — a long-time aeronautical engineer at Boeing — puts up a chart titled, “Receivers Are Going to Get Complicated.”

Well, sure, I think to myself, that stands to reason.

His chart lists the various systems and the frequencies that their signals will be on, and then asks the question: How many different kinds of position solutions could there be?

Turns out, by the time all the current and planned signals come on line over the next decade, GPS by itself will have seven different possible combinations for just the signals in protected safety-of-life frequencies (omitting GPS L2): L1 only, L1C only, L5 only, L1 & L5, L1 & L1C, L1C & L5, and L1, L1C, L5.

Then Murphy goes to the next slide: “Receivers Are Going to Get Complicated (2).”

“Uh-oh,” I think to myself.

This slide even starts out with a formula. Total combinations (Nc) for a constellation with n signals is:

Bottom line: Murphy’s conservative estimate totals 441 different modes that a receiver could operate in. Toss in a satellite-based augmentation system that adds one signal option to each signal set, and the number doubles. Pity the poor manufacturer who has to sort out the trade-off analysis for that one!

Yeah, we were all thinking this was an interesting twist on Murphy’s Law — “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.” Perhaps the “too much of a good thing” variation.

It was almost a relief when he turned to his next slide: “Interoperability — the Political/Institutional Problem.”

Difficult as they now appear, sorting out frequency-sharing issues among the various providers may turn out to be the easy part.

So, initiatives at the highest political levels — such as the more internationalist and cooperative approach outlined by the Obama administration in a recent space policy statement — are sorely needed. So are practical projects such as the proposal for an Asia-Pacific multi-GNSS Demonstration Campaign recently offered by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

Meanwhile, the efforts of the International Committee on GNSS (ICG), which holds its fifth full meeting in Italy this coming October, may play a more important role than ever. The ICG secretariat, hosted by the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs, recently published a handy compendium outlining where we are now: “Current and Planned Global and Regional Navigation Satellite Systems and Satellite-Based Augmentation Systems.”

Interesting times, and they will require much good will and many solid efforts too keep them from becoming too interesting.