The nation’s leading GPS experts are struggling to quantify how the world’s premier navigation and timing system affects the U.S. economy, an effort critical to building a political firewall around GPS spectrum in the face of ballooning demand for broadband capacity.

The nation’s leading GPS experts are struggling to quantify how the world’s premier navigation and timing system affects the U.S. economy, an effort critical to building a political firewall around GPS spectrum in the face of ballooning demand for broadband capacity.

“It is an impossible question,” said James Schlesinger, chairman of the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board. “It’s methodologically harder than evaluating the Gross Domestic Product. What we are being asked to do is calculate something that is incalculable.”

The research challenge was highlighted in comments by Jules McNeff, vice-president at Overlook Systems Technologies, in the current issue of Inside GNSS: "In the case of GNSS services, these [benefits] are more difficult to quantify because they are both direct and indirect, include second- and third-order benefits, and are not simply revenue streams from direct subscription services. They are spread across all economic sectors and represent revenues from increased efficiencies in logistics and related economies of operation, improved safety, reductions in personnel costs and exposure to hazards, and others."

The PNT advisory board, which agreed to look at economic impacts last year at the request of the National Executive Committee for Space-Based PNT (ExCom), spent part of its December meeting weighing reports from three researchers it had commissioned to find and assess data on GPS benefits and spectrum valuation that others had already gathered. One of the most recent studies discussed was Issue 3 of the GNSS Market Report, a study released by the European GNSS Agency (GSA) a few months ago.

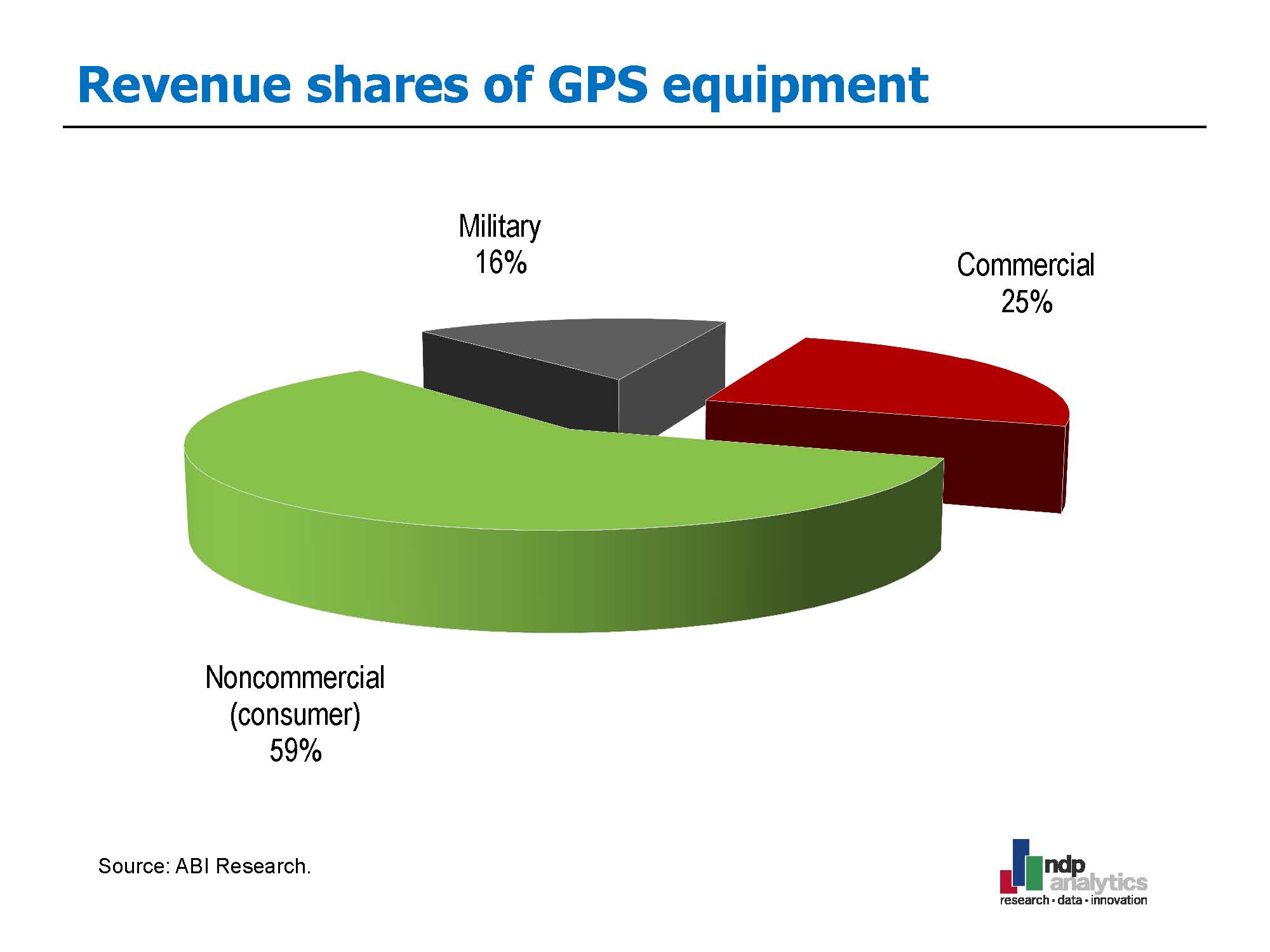

GSA found that the annual shipment of GNSS devices worldwide jumped from 125 million in 2006 to roughly 850 million in 2012, said Nam Pham of ADP Analytics. By 2022 that is expected to grow to 2.5 billion units a year, bringing the total number of GNSS devices in circulation to around 7 billion — enough for every person on the planet to have one. The total global revenue for GNSS devices was forecast to grow to $143.9 billion by 2022 from $59.4 billion in 2012.

According to the GSA study, the GNSS market is dominated by location-based services (LBS), said Pham, a category that includes GNSS-enabled consumer products such as smart phones, tablets and digital cameras. The GSA found that though such devices make up the vast majority of the GNSS devices, they likely will be responsible for only 47 percent of the revenue from 2012 to 2022 — a scant lead over the 46.3 percent generated by rail and road applications. Surveying and mapping is expected to produce 4.1 percent of revenue for the period followed by agriculture and aviation/marine uses at 1.4 and 1.3 percent respectively,

Of the global activity in 2012, North America generated more than 70 percent of the aviation revenue and nearly 60 percent of that from agriculture. Thirty percent of LBS revenue was from North America, while surveying and road applications came in at around 25 percent each, rail at roughly 15 percent, and maritime applications at around 10 percent.

Direct revenue is only one of the economic factors for any given industry, said Pham. Companies buy raw materials and hire workers who in turn use their wages to buy homes and other goods. Pham estimated that GNSS manufacturers contributed $32 billion in output and $6.8 billion in earnings to the U.S. economy, generating more than 105,000 total jobs in the process. He based his figures on the 2011 U.S. Census Bureau Annual Survey of Manufacturers.

Work with the Data You Have, Not the Data You Want

The European study, however, appeared incomplete to at least one member of the board — an assessment with which Pham agreed.

“There is something missing there,” said board member James Geringer, a former governor of Wyoming. “I think of all the other downstream applications . . . any of the aerial imagery that uses GPS. It is a meaningless service without the GPS or other coordinate references,” Geringer said. The geospatial information system (GIS) firm ESRI, where he serves as director of policy and public sector strategies does $1 billion in annual business by itself, he said, adding, “You’ve got a great big hole in there somewhere, it seems to me.”

Geringer’s point illustrated the shortcomings in the available data at the heart of a wide-ranging discussion within the board, which was weighing how to approach the question and at what point it should present numbers — even preliminary numbers — to the ExCom.

It is like trying to measure the value of energy, Schlesinger said

Even so, the European study appears to be one of the best available in that it is recent — it was released in October of this year — and broad in scope.

Most of the economic studies on GPS tend to be very narrowly cast and 5 to 15 years old — so old they fail to capture the benefits of new applications and rapid shifts in technology, said spectrum expert Bartlett Cleland,

Cleland presented the result of a literature review on the market research. Among those new applications, he said, are GPS-enabled clothing, including shoes that help you find your destination, and GPS-based sports analytics that teams can use to assess and improve their play against a specific opponent.

Moore’s law that computing power doubles and costs are halved every 18 months is “roughly applicable” to the GPS industry, Cleland said, and is a realistic guide for how often you need to do new studies on an industry.

“About every 18 months you have to reshuffle the deck,” he said.

Getting Equipped for the Spectrum Gold Rush

The need for better data on PNT’s economic impact was made clear during the fight over LightSquared’s proposal to repurpose spectrum near the band used by GPS, thereby creating what tests eventually showed would be debilitating interference to GPS receivers. The economic data presented by the wireless broadband industry at the time seemed to give the telecom companies the upper hand in the policy debate, said Geringer.

Many studies support the argument that broadband needs more spectrum, said Cleland. The number of studies is partly due to the industry being well organized.

Interest in the subject is global, he said, and some broadband companies have the cash to support economic-benefit research for their industry. For example, he said, a report from the International Telecommunications Union and the United Nation’s Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization details the global economic effects of broadband with GDP numbers, penetration to growth rates, and analysis of ancillary benefits such as eradication of poverty or increased educational opportunities. Related reports are also available as well from the Telecommunications Industry Association and even individual companies such as CISCO.

“With other industries fighting for the finite raw material of spectrum,” Cleland said, “the GPS industry must continue to generate and update its economic valuation work or risk being marginalized in policy debates.”

That fight is only going to become more intense as companies scramble to capture consumers who want “everything, everywhere,” said John Kneuer, a former National Telecommunications and Information Administration chief and a spectrum policy expert. Wireless carriers are trying to provide content inside the home, cable companies like Comcast and DISH are devising ways to deliver content outside of the home, and applications providers like Google and Amazon are maneuvering to become content conduits.

The broadband industry is converging on a ‘singularity” where all the companies are competing with each other to control the same customers — and it all rides on the availability of spectrum, said Kneuer.

The Advisory Board will continue its work into next year, said the board’s vice chairman, Brad Parkinson, while cautioning against the expectation that they could come up with a single number that policy makers could use for an ‘elevator speech.’

The sum of the economic effects of GNSS throughout the world “is certainly many tens of billions of dollars per year, but the analysis to date tends to be based on cost rather than value,” Parkinson said. ‘There is a good reason for that. It is really hard to come up with the total value. Hence, we tend to undervalue the GPS contribution.”

Although Cleland said that he didn’t see why “GPS doesn’t sit right alongside a lot of these technology issues in importance,” he said it was unlikely that the pressure on GPS spectrum will ease.

“The broadband debate and the need for spectrum will never end,” said Cleland. “It will never end.”