Will the network, which some are still fighting, be ready for a September rollout, and if so, what are the implications for GPS and the people who rely on it?

It’s been two years now since the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) authorized Ligado to use portions of the L-band for low-power terrestrial mobile satellite services (MSS), which many say will interfere with GPS.

In that time, the FCC has either denied or failed to act on motions filed by federal agencies and commercial industry. Congress stepped in, using the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to pull its purse strings tight and demand some answers.

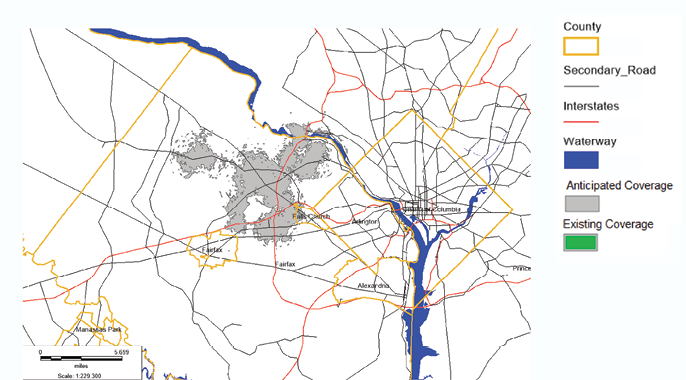

Meanwhile, Ligado has pressed on. The company says it will launch its first systems by the end of September. It recently published a map of its preliminary coverage (see p. 14).

An earlier attempt by major telecom companies to roll out 5G, with similar GPS interference concerns, resulted in an eleventh hour safety campaign and program delays, which I reported on for Inside GNSS earlier this year. Will Ligado become yet another chapter in the book of 5G rollout blunders?

Looking Back to Look Ahead

The Ligado saga has played out in the public arena for more than two decades. It began in 2004 when Ligado’s predecessor, LightSquared, obtained FCC spectrum licenses for about 1,725 ground stations.

In 2010, the company expanded its request to include up to 40,000 base stations. By 2012, the FCC halted the project after preliminary testing revealed significant GPS interference (e.g., jamming airplane receivers up to 12 miles away). That same year, the company filed for bankruptcy.

Ligado reemerged in 2015. In the interim, even as it modified its FCC applications, additional testing continued to reveal GPS-interference problems, according to gps.gov/spectrum/ABC.

Ultimately, on April 19, 2020, over federal and industry objections, the FCC granted Ligado a conditional and modified license (FCC 20-48) for its national MSS network. Opponents struck back with Motions to Stay (meaning to halt) and to Reconsider.

Congress stepped in toward the end of that same year. Section 1661 of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) precluded the Department of Defense (DOD) from using appropriated funds for technical or information exchanges with Ligado or to retrofit affected equipment. It required the DOD to submit estimates of reimbursable costs for such a retrofit. It also directed the DOD to charter an independent technical review by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies). The report, the NDAA said, was to be delivered to Congress within 270 days.

In a bold counter move, as one of the final acts of the outgoing administration, in January 2021, the FCC denied the federal request (via the National Telecommunications and Information Administration or NTIA) to halt Ligado’s action on the license. The Reconsideration Petition still remains pending.

It was not until September 2021, past the Congressionally-mandated report deadline, that the Academies’ ad hoc committee (“Review Committee”) began its work. The group planned to close the record to additional evidence at the end of April.

Review of the Review

The Review Committee’s findings were already overdue when it started. That said, the group, led by Committee Chair Michael McQuade, Ph.D., Strategic Advisor to the President at Carnegie Mellon University, has been busy.

As one of its first orders of business, the Committee reviewed, and waved off, potential conflicts of interest (COI) of two of its own members, Dr. Nambirajan Seshadri and Dr. Mark Psiaki. Sehsardi holds ownership of stock in Verizon Communications; Psiaki consults for and receives research support from a communications systems design and manufacturing company that uses Iridium Communications Incs’ satellites. The COI drill appears to have missed Jennifer Lacroix Alvarez, who, according to her posted bio, “was CTO and is currently CEO of Aurora Insight, which provided Ligado Networks Inc. with consulting services in 2018.”

The team appears to have been fully formed by November 18, 2021. It aims to address these three issues:

1. Which of the two prevailing proposed approaches to evaluating harmful interference concerns—one based on a signal-to-noise interference protection criterion and the other based on a device-by-device measurement of the GPS position error—most effectively mitigates risks of harmful interference with GPS services and DOD operations and activities.

2. The potential for harmful interference from the proposed Ligado network to MSS including GPS and other commercial or DOD services such as the potential to impact DOD operations and activities.

3. The feasibility, practicality and effectiveness of the mitigation measures proposed in the FCC order with respect to DOD devices, operations and activities.

In the 7 months since its inception, the committee has held 23 meetings. Almost half of its sessions (10) have been completely closed to the public, including all of its meetings after January 27, 2022, to now.

The public record lists more than 83 documents. Ligado submissions account for more than half (43) of all the documents gathered by the Committee. The next closest in terms of volume amounts to 11 documents, from Iridium.

The record also contains more than 17 hours of video testimony from both sides of the aisle and third parties. The lines were drawn in the lineup: Ligado, Roberson and Associates and the FCC versus the NTIA, Department of Transportation (DOT), National Advanced Spectrum and Communications Test Network, Brad Parkinson Stanford University, Garmin, Trimble, Iridium, Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, American Meteorological Society’s Committee on Radio Frequency Allocations, National Society of Professional Surveyors (NSPS), Helicopter Association International (HAI), Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc. (ASRI), RTCA and several commercial aviation industry organizations and experts.

Garmin’s Scott Burgett explained the concerns succinctly. “There are four internationally recognized and defined components of GPS performance that are critical to preserving the performance of a myriad of applications: accuracy, integrity, availability and continuity,” he said. “The Ligado order affects each of these. It raises troubling unanswered and safety-relevant questions for certified aviation.”

History Repeats?

Given the recent kerfuffle between the FAA and the 5G crowd over avionics interference concerns, the view presented by the commercial aviation industry merits close attention. This is especially so as the entire crewed aircraft industry, and parts of the uncrewed aircraft crowd, have challenged the FCC’s Ligado order.

ASRI’s Andrew Roy said, “Spectrum is key to how aviation operates…We have to meet higher standards. Aviation is the safest mode of travel by design. It needs to be a certainty. It’s not an ‘80/20’ thing.” He warned that while the 2018 version of Ligado’s plan seems to emit more localized interferences, “…what is still out there can have a significant effect on users, compounded by the unknowns based on conditions applied and current aviation practices.”

Bryan Lesko, chairman aircraft design for the Airline Pilots Association (ALPA), a 20 year professional pilot who is rated in 10 different jets with more than 12,000 hours of flight time, explained the importance of GPS to commercial flight. It is deeply integrated into aircraft systems, from calibrating aircraft clocks to the transponder functions that allow them to be seen on air traffic control radars and to squawk for ADS-B. It is the lynchpin of critical safety-of-life systems such as Terrain Awareness System (TAWS) for airplanes and the sister functionality for helicopters (HTAWS). That’s “why this is a really big deal and why we should really be concerned about this,” he said.

John Shea, director of government affairs for HAI said that for low altitude operations within the 250 to 500 foot diameter cylinder around Ligado base stations, helicopters would be flying blind. This rings true even around heliports covered by Part 77 Obstacle Clearances. Perhaps more troubling, about 15,000 private and aero-med heliports would not be accounted for or protected under the FCC order. These estimates may be low because, according to NASA, the FAA does not include many hospital heliports and Predesignated Emergency Landing Areas in its databases.

The testimony revealed that these same GPS-interference concerns apply to the almost 850,000 registered uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS). Almost all of these use uncertified GPS.

The agricultural aviation community expressed concerns specific to its unique operations. These missions occur across every state. They account for 25% of all croplands (127 million acres). Scott Bertthaurer, Director of Education and Safety for the National Agricultural Aviation Association, said “If we lost GPS we would not be able to make the passes accurately.” This would have negative impacts across the $37 billion market in the U.S. for corn, soybean, wheat, cotton and rice alone.

In a March 25 return volley, Ligado essentially states all of this is much ado over nothing. It amended its license in 2018 to address the FAA’s determination that 9.8 dBW on the lower downlink would protect all certified aviation GPS devices. UAS, it said, are so high tech that “The suggestion that drones are at risk from Ligado base stations operating at 10 Watts just doesn’t hold water.” Even so, it continues, even the FAA’s recent beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) advisory rule making committee suggested that alternate technologies should be used in GPS-denied environments. The reply admits, however, there are still issues to resolve to protect Inmarsat SATCOM devices from interference. According to the letter, Inmarsat is responsible for resolving those problems.

So, What are the Feds Doing?

Other than testifying before the committee, the feds have otherwise stayed relatively mum.

The NTIA has been representing all federal agencies in this matter and took lead in the hearings. While the DOT, which serves as the Civil Lead for GPS, also testified, the DOD did not. Perhaps this is why the committee sent several follow-on questions directly to the DOD. Answers were due April 15.

Getting at the heart of the issue, the committee specifically asked, “Can the DOD provide information on the availability or lack thereof of practical bandpass filters that would allow M-code receivers to function with manageably low interference from aliased versions of the permitted power in the Ligado bands?” DOD’s response:

Repair and Replace: Military platforms have numerous GPS receivers, each of which would need to be independently evaluated for impacts. When impacts are found, the military would need to modify or replace all receivers, which would take over a decade.

Even assuming the DOD has a filter fix in the works, this will not address commercial users. The DOT remains “concerned about the millions of receivers that will experience interference.” In response to an Inside GNSS query, the DOT’s spokesperson said the agency’s “position remains unchanged” since its 2020 briefing to the FCC. Highlights include:

• Costs to federal and private users: “Tens of Billions of Dollars…Lives Lost…People Injured”

• General aviation GPS (Non-IFR) will be affected up to one kilometer

• HTAWS could be severely harmed

• The majority of civil GPS receivers are not U.S. Government devices and will not qualify for repair or replacement paid by Ligado.

The DOT also echoed the aviation community’s concerns, noting “unresolved issues relating to aviation operations and safety.” The FAA apparently still has not completed an exhaustive evaluation of operational scenarios relating to impact zones, including in densely populated areas. As noted before, the DOD said it would take about 10 years to see how filters might work. Many unknowns continue to linger.

Predicting the Future

The jury is still out, but even as early as October 2021, some members of the Committee seemed to be inclined to fault federal agencies for not meaningfully participating in the FCC process. Take, for example, these comments by Alvarez:

“I think, just in terms of lessons, the FCC had a totally transparent process that is supposed to work through issues like this. And at no point during that process did the people who are now asking me to do this study, say ‘Here is the data that we are providing to you and to the other experts in this process that will enable you to understand why we are so concerned.’ …If people participate willingly and fully in the process it can work, but all of the agencies have to be willing to do that.”

The Review Committee findings aside, there are those who believe Ligado simply won’t be able to execute by September. Given the controversy surrounding Ligado’s spectrum, it may literally be a tough sell. In a recent piece for Forbes.com, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, the DOT’s former deputy assistant secretary for research and technology, notes that front-runner Verizon has not linked up with Ligado, as anticipated. Instead, Ligado has pivoted to employing a spectrum broker, Select Spectrum, according to a company news release, to peddle its wares. She also alludes to the possibility that the FAA and other federal agencies will throw down the red card in the face of avionics interference claims as they did during the recent 5G launch.

If not, and Ligado does succeed in rolling out its transmitters, Furchtgott-Roth predicts, “This will swamp GPS in a number of places. People will not be able to use their navigation systems without interference. Firefighters and emergency workers won’t be able to get to people’s houses when they have problems. Precision agriculture and precision construction won’t work effectively. Everything depends on reliable GPS.”

And so it does. The question is: Will GPS remain reliable post-Ligado?