Stas Sila-Novitsky (left) and Javad Ashjaee. Photo by Marc Cheves, American Surveyor

Stas Sila-Novitsky (left) and Javad Ashjaee. Photo by Marc Cheves, American SurveyorVery sad news from Moscow. Earlier this month, Stanislav Sila-Novitsky — Stas to his friends and colleagues — died unexpectedly after a short illness.

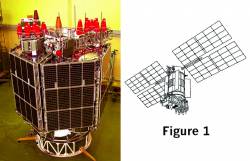

A member of the executive staff of Javad GNSS, Sila-Novitsky had a long career in space electronics engineering. During the Soviet era, he was the department head with the Russian Space Agency’s Institute of Space Device Engineering, which was responsible for the development of the overall GLONASS system electronics.

Very sad news from Moscow. Earlier this month, Stanislav Sila-Novitsky — Stas to his friends and colleagues — died unexpectedly after a short illness.

A member of the executive staff of Javad GNSS, Sila-Novitsky had a long career in space electronics engineering. During the Soviet era, he was the department head with the Russian Space Agency’s Institute of Space Device Engineering, which was responsible for the development of the overall GLONASS system electronics.

Around 1990, Sila-Novitsky joined Ashtech Inc., which had established a Moscow operation in the final years of the Soviet Union. It was the beginning of a 20-year relationship with Javad Ashjaee and the series of companies that the latter operated in Russia.

During those chaotic and difficult economic times, I heard from more than one Russian engineer this observation about the government, “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work.” And, like many Russians, Stas’s humor also tended toward the ironic — but it was a gentle irony that I never saw veer into sarcasm.

I first met Stas in the mid-1990s but didn’t really get to know him until I visited Moscow in 2005 and 2007. Somewhat taciturn around strangers in settings outside Russia, he clearly became more comfortable, even expansive in his native land.

Although several pleasant memories suggest themselves — outings to Red Square on Moscow’s Metro system — one stands out: the afternoon that he took time away from his work responsibilities to guide a small group of us personally through Moscow’s amazing Izmailovsky Craft Market.

He was careful about his guests’ well-being. At night, when Stas accompanied us back to our hotel, he led us down this street, not the other one that looked the same but with dangers in the shadows. Then we watched as he walked back alone to Leningradsky Prospekt, where Stas would wave down a passing private car willing to serve as one of Moscow impromptu taxis and take him home.

I never learned a lot about Stas’s personal background. As echoed in his name, his family had come to Russia from Poland — or Russia had come to it as the borders moved back and forth in the 19th and 20th centuries.

I always meant to find out more about that history and thought there would always be another right time for that. But it never came, and now that moment has gone forever.

So, Stas’s passing teaches us the lesson once again: tell all our stories and ask for all theirs, drink all the toasts, take all the photos, visit all the sites desired but unseen, voice all our apologies and welcome their joys and regrets. When the opportunity to meet old friends appears, don’t turn aside or rush right by.

For life is uncertain, but death is not. And time flies; it doesn’t take the bus.