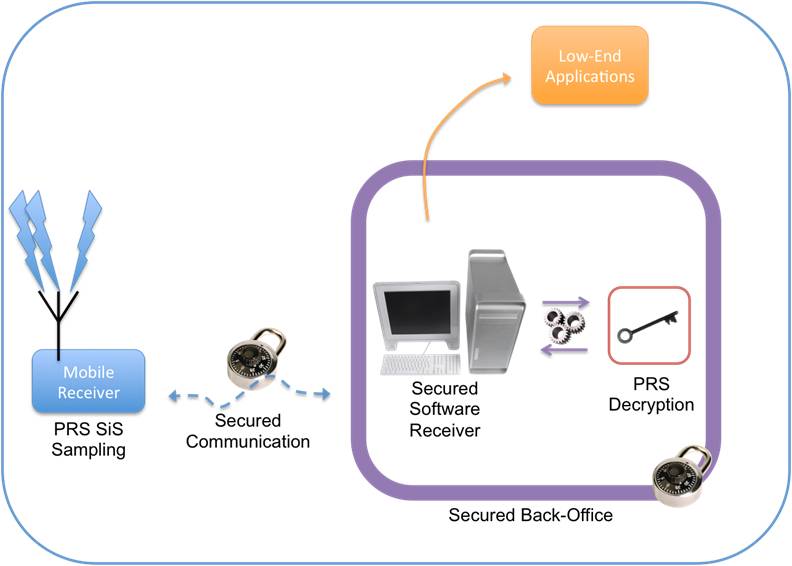

Conceptual design of ULTRA (ultra low-cost PRS receiver)

Conceptual design of ULTRA (ultra low-cost PRS receiver)When European leaders first took up the idea of creating their own GNSS system nearly 20 years ago, they held up the concept of civilian control as a crucial differentiator from existing services operated by national military establishments.

As Galileo nears its operational phase, that principle may manifest itself in a surprising form: the opportunity to offer a range of security-oriented positioning and timing solutions in place of the all-or-nothing alternatives on encrypted services maintained by defense agencies.

When European leaders first took up the idea of creating their own GNSS system nearly 20 years ago, they held up the concept of civilian control as a crucial differentiator from existing services operated by national military establishments.

As Galileo nears its operational phase, that principle may manifest itself in a surprising form: the opportunity to offer a range of security-oriented positioning and timing solutions in place of the all-or-nothing alternatives on encrypted services maintained by defense agencies.

Under a new regulation nearing approval by the European Parliament, the European GNSS Agency (GSA) will continue to oversee Galileo security matters. This includes the physical security of Europe’s GNSS infrastructure, but more importantly for user communities, the rollout of the public regulated service (PRS) and associated security arrangements among participating member-states the European Union (EU).

Unlike the other GNSS programs for which military officials developed rigorous protocols to manage the distribution and security of the technical means for using encrypted signals, civil institutions will control the access to Galileo’s encrypted PRS.

Now the Galileo program is looking for technological and operational approaches able to provide a graduated range of secure PRS options that could bring lower-cost solutions and wider use.

This could expand PRS applications beyond the primary customer base long foreseen among military and public safety groups such as police, border control and customs, and emergency services.

“A lot of people are stuck with the idea that security is strictly a military concept,” one security official told Inside GNSS. “But the distinction between civil and military may be fading.”

New user groups could include utilities, stock exchanges, transportation operations, and financial services, many of whose operations are transnational or even global in scale.

Meanwhile, the GSA has begun work on two Galileo Security Monitoring Centers (GMSCs) — essentially service centers for the PRS — sited in France and the United Kingdom.The French GSMC is being built within a military complex, the Camp des Loges, at a few kilometers from Saint Germain en Laye.

According to the GSA, the GSMCs will be in charge of several major tasks when completed, including: overall management of the Galileo system security, management of access to the PRS, command and control of European GNSS in accordance with the Joint Action instructions that could be implemented in times of crisis, and provision of PRS and GNSS security expertise and analysis.

Olivier Crop, head of security for the GSA since 2006, has recently been named manager of the GMSCs and will continue to report directly to GSA Executive Director Carlo des Dorides.

The new GNSS regulation will continue the role of the Security Accreditation Board (SAB) and GNSS Security Board, supported by the GSA, to establish EU-wide standards and protocols for PRS equipment and use.

As long as their procedures comply with the overarching rules and requirements for security overseen by the GSA, each member-state is responsible for determining who can gain access to PRS capabilities within its borders, and dealing with any problems that may arise.

Participation in the PRS is optional for each member-state, as are decisions about how the PRS is to be used and by whom as well as whether users should pay for the service.

Growing Interest in PRS

Willingness to consider both military and non-military uses of PRS appears to be increasing among EU member-states.

Responding to an EC study in 2006, at least 13 nations expressed an interest in using PRS for defense uses. On the contrary, some nations — most prominently, the United Kingdom — that had access to the encrypted GPS signals (such as P/Y and M codes) under NATO or bilateral agreements with the United States, appeared skeptical about the need for PRS or its utility for military purposes since it would be under military control.

Under the previous Labor government, the UK was a determined holdout against use of the PRS, but has taken a more prominent role in preparations for use of PRS in the EU. For example, a British national serves as deputy head of the SAB, which is chaired by a French representative.

The British government has named the UK Space Agency as the Competent PRS Authority (CPA) for the nation and intends to establish a secure platform that will enable PRS access management during its initial operational capability (IOC), now expected around 2016 or later.

EU member-states have until the end of 2013 to identify their competent PRS authority. The GSMCs will assess the capabilities of the local PRS authorities.

By the end of 2015, the GSA expects to have a good security system in place across Europe and can begin to provide access to the PRS signal beginning in 2016 with full service coming in the following years.

As one European official said, PRS is “not needed so much now. We’re interested in having the capability for the unknown security environment of 2016-19.”

Manufacturers Consider a Bigger Market

A PRS workshop at the recent European Space Solutions conference in London brought together public officials, companies, and users interested in exploring use of PRS. Although UK officials have focused on non-military uses of PRS, British manufacturers such as QinetiQ say that they are concentrating on building PRS equipment for military customers.

Substantial interest has been expressed in building receivers that can use both the planned GPS military M-code and Galileo’s PRS, although recent technical studies have suggested that the different signal structures might not make the two signals as compatible as once hoped.

Beginning in 2014, a series of PRS pilot projects will focus on testing and early use of the PRS service, including validation of the signal and development of applications and test scenarios. Based on meeting the requirements of nine criteria, more than 30 companies have already been authorized by the GSA to work on PRS receiver and security module manufacturing.

Manufacturers could design PRS decryption and signal-processing capabilities into a single chipset to provide secure navigation on top of secure communications. But establishing a system based on secure PRS modules and decryption keys is cumbersome even with modern over-the-air keying techniques and is also expensive.

A recent study cited by the GSA has shown that prospective civil markets don’t want to pay more than five percent higher prices for the user equipment.

Instead, the GSA supports development of a gradation of capabilities, ranging from full standalone PRS, anti-jam, robust receivers down to low-end receivers that have no security qualities in themselves – a trade-off of security capabilities and cost.

One example of an approach that could provide a level of security with lower cost and less risk of security breaches would use packets of unprocessed PRS data received by user equipment and transmitted over a secure communications link, such as professional mobile radio (PMR), to a secure PRS facility. There the “snapshot” PRS data would be processed and a position retransmitted back to the user.

A team led by M3 Systems, a research and engineering consultancy based in southwestern France and Belgium, is working on a system design that would support this approach. Co-funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program managed by the GSA, the 23-month ULTRA (ultra low-cost PRS receiver) project was launched last February. (See accompanying figure.)

EU member-states will have to come back to the SAB to get authorization to put PRS equipment on the market. The GSA is developing a catalog of test lab facilities with PRS expertise in the various member-states.

The GSA has proposed to the European Commission that it be allocated funds to support research to work out solutions for PRS user equipment — possibly developing intellectual property that could be shared among EU member-states.

The PRS workshop held during the recent London conference posed the question: Do we have PRS1 and PRS2 or do we have one PRS that can be used by both?

“If you have a single PRS receiver on the market that is bad, you are compromising the collective security of all the other users,” one official points out.