The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is advancing beyond simple assessment of the risks that GPS disruptions pose to critical infrastructure and is considering the development of new technology to mitigate jamming and spoofing while working with vendors to integrate that technology into receivers.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is advancing beyond simple assessment of the risks that GPS disruptions pose to critical infrastructure and is considering the development of new technology to mitigate jamming and spoofing while working with vendors to integrate that technology into receivers.

Sarah Mahmood, program manager for the Resilient Systems Division within DHS’s Science & Technology Directorate, said the agency has let a number of contracts and has work under way on methods to identify and locate GPS interference and jamming using the location capability that already exists in cell phone apps. The agency is also exploring how to achieve a similar capability to counteract spoofing, she told a June 4 meeting of the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board.

Although DHS has made presentations to the advisory board before, this one was notable for its level of technical detail and the clear seriousness with which the agency had tackled the issues. Advisory board members paid close attention, with many asking for clarifications.

“Seeing DHS just starting to really dig into these issues — I applaud it very much and I think the whole board does too,” said Brad Parkinson, acting board chairman and a former chief of the NAVSTAR GPS Joint Program Office (now GPS Directorate).

A Critical Infrastructure for Critical Infrastructures

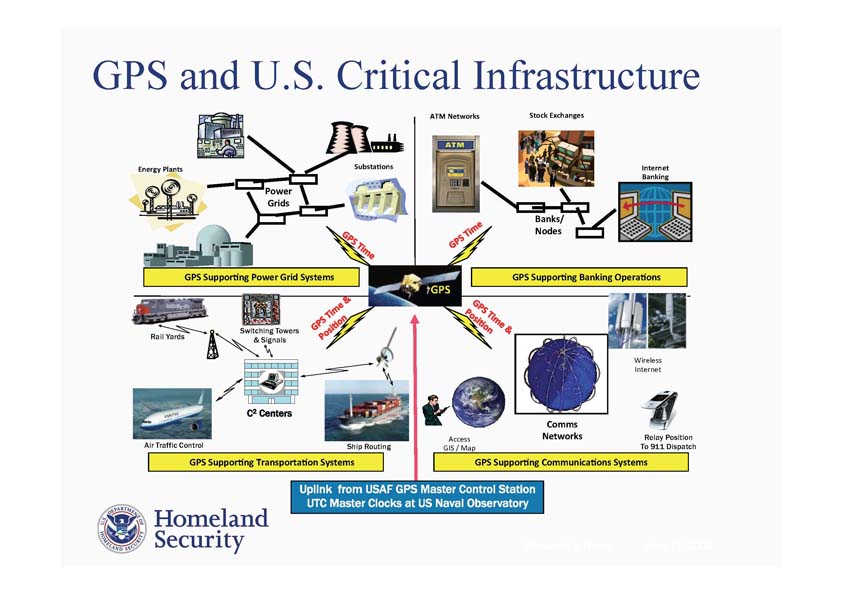

Mahmood said her group has been studying in detail the potential impacts of GPS disruptions to the nation’s energy and communications networks. Although federal agencies have identified 16 critical infrastructure sectors — the majority of which would be adversely affected by an extended loss of GPS timing data — Mahmood said that DHS elected to do a “deep dive” into these two particular sectors because Presidential Policy Directive 21 (PPD 21) on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience highlighted them as “being uniquely critical because of the enabling functions that they provide.”

The Resilient Systems Division wanted to find out how GPS is being used, she said, why it’s being used, if there are the backups in place, and how vulnerable the sectors are. To do this they looked at the electrical sector both as it exists today and as it is projected to look five years from now when the electric grid is expected to incorporate more synchrophasors — a key vulnerability, she said — and shift to a “smart-grid” approach incorporating more computer-based remote control and automation.

The most stringent timing requirements they found range from one second down to less than one microsecond.

“GPS is still the primary reference for wide area synchronization at the one-microsecond level throughout the grid,” Mahmood said, noting that there were few if any, timing backups able to last more than a few hours at that level.

The electric grid equipment most at risk, besides the synchrophasors, includes that used for detecting faults in the transmission lines, recording disturbances, monitoring power quality, metering, managing the system management, and supporting distributed energy sources.

Although the actual impact of a disruption depends on the cause, she said, an attack with multiple low-power jammers could result in the loss of the ability to monitor and control the system. But spoofing represents a different kind of threat.

“If we have a coordinated spoofing attack, and you project what the system is going to look like in 5, 10, 15 years — when we’re really depending on synchrophasor measurement units, assuming we haven’t added any type of protection to them — a coordinated spoofing attack could, in theory, bring down part of the grid,” Mahmood said. “And so we find that spoofing is really probably the most dangerous threat to the grid.”

A Failure to Communicate

DHS also looked at the communications network as it exists now and, given that its infrastructure is evolving more quickly, how that network is projected to be structured just three years from now. DHS found that the timing requirements ranged from 1.5 microseconds for cellular networks to 62.5 microseconds for the PSTN (public switched telephone network) and the Internet.

GPS is the primary timing mechanism for communications, she said, and loss of the signal would affect equipment ranging from SONET/SDH, SynchE, and clock nodes to mobile and landline switching centers and transceivers for cellular and micro-cell networks.

Communications systems seem to be less susceptible, however, to both intentional and unintentional interference, she said. For example, the cellular network is more susceptible to jamming and spoofing than the regular landline network, she said, but even an attack on the cell phone system would have a limited impact because it would be directed at the cell towers, and therefore would be localized.

A MITRE Corporation report on how to mitigate the risks to GPS suggested a range of options starting with simple fixes such as placing the antennas where they are less likely to be noticed by adversaries or to experience multipath interference. The report also suggested upgrading to high gain or multiband antennas, using multi-constellation receivers, and integrating devices that could extend the holdover time — the time interval in which a device can operate effectively without GPS.

MITRE also suggested establishing a nationwide backup for timing signals — either eLoran or a system that would provide position navigation and timing information through the cloud.

While standalone anti-jamming products are emerging, Mahmood said, commercially available spoofing detection and localization products have not appeared that are designed for private sector use.

“That’s kind of a key area we might want to consider moving forward,” Mahmood said.

Parkinson summarized board member suggestions supporting development of a GPS threat model. “The threat model is not simply for a single sector,” he said. “We really need a national threat model which can act as a guide to action, even if it isn’t 100% accurate.”

Funding the Search for Solutions

DHS is putting some funding behind its desire for options. The agency awarded SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) contracts four companies to develop low-cost ways to detect and localize sources of fixed and mobile disruption. The companies — Coherent Navigation (Foster City, California), NAVSYS Corporation (Colorado Springs, Colorado), Scientific Systems Company (Woburn, Massachusetts) and Toyon Research Corporation (Sterling, Virginia) — were to study the energy sector plus one other sector in which they were interested.

Coherent Navigation was selected for a follow-on contract and is now prototyping a smartphone-based network that uses location data from existing phone applications to detect interference and find its source. The goal is to sound an alert within an hour of a disruption occurring and locate the source to within 500 meters.

Within about a year, Mahmood said, DHS will be looking for partners to help field test the technology and invited interested parties to contact her office. Her contact details are as follows: Sarah Mahmood, Program Manager, HSARPA/RSD, DHS Science & Technology, <sa***********@*hs.gov>, telephone 202-254-6721, mobile 202-360-2360.

DHS is sensitive to the privacy implications of such an approach, which might be available to critical infrastructure managers as a subscription service. “We won’t be collecting any location data,” Mahmood said.

Clear and Present Danger

Finding and stopping GPS interference may be even more important than originally thought. During the first round of contracts, which lasted about six months, one of the vendors tested a number of receivers, including a high-quality reference station receiver, a popular network time server with quartz and rubidium oscillators, and a time and frequency receiver with a quartz oscillator common to cell towers.

“All the receivers were vulnerable to jamming and spoofing,” Mahmood told the PNT advisors. “It was a little surprising how some of the receivers actually behaved in that the receiver logic didn’t appear to be able to differentiate what was going on and be able to actually switch over to backup timing or something like that. It is a bit of a concern for us, because it is one thing to say that you can switch over to backup timing if GPS is unavailable but if your receivers aren’t able to recognize that GPS is unavailable, or you’re being spoofed, the capability of backup timing is almost irrelevant. We need to make our receivers smarter."

Inside GNSS has learned the DHS science team may begin new projects as early as next fiscal year. They are considering additional testing, Mahmood told the group, as well as beefing up education and outreach to infrastructure owners. The agency also wants to develop cost-effective ways to pinpoint and deal with spoofing. The later would require working with hardware manufacturers, she said, to be able to integrate solutions into the hardware as a way to keep costs down and spur adoption.

The government is not in a position to force private companies, which own most of the country’s critical infrastructure, to upgrade their equipment, she said in response to a question about integrating the new technology. The strategy, therefore, is to work with equipment providers to develop and incorporate changes and to educate prospective users as to the real risks of GPS vulnerability.

Many firms, her office found, don’t believe the threat from GPS disruption is real or are unaware that their existing equipment is as vulnerable as testing has now demonstrated. DHS has also discussed equipment certifications, although no decision has been made to pursue this option.

“I think the strategy really becomes this two-pronged strategy,” Mahmood told the board. “It is empowering industry, the critical infrastructure industry — the critical infrastructure owner and operators — with knowledge that this is a key issue and they need to start looking for products that have this capability built into it. At the same time we propose to work with the equipment vendors to actually develop the key mitigating technologies that they can embed into their existing products.

“And so the strategy is that if we approach it from both sides, then hopefully we’ll be able to have a low-cost product that’s capable of protecting the grid — then we have the interest from the industry and the understanding that they do need this equipment and they do need this solution.”