The smartphone and its various everyday apps link us to GPS, Wi-Fi networks, Bluetooth LTE, audio and cell tower proximity that help us find out where we are and tell us how to get to where we need to go, down to precise latitudes, longitudes and altitudes, accurate to within a few yards. So who should have access to this information?

The geolocational privacy issue remains largely unresolved. Some in the federal, state and private sector have attempted to address it through legislative and legal action. This article reviews the geolocational privacy landscape and highlights impactful issues that businesses need to watch.

Privacy Reigns Supreme

Private access to geolocational information remains relatively wide open, unless state laws address it (more below on this).

On the other hand, government access to this same data can raise constitutional issues under the 4th and 14th amendments, which protect privacy by prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures.

Normally the government must obtain a warrant to access information when a reasonable expectation of privacy exists. Cases often revolve around this issue of reasonableness.

A trilogy of Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) cases form a strong basis for the notion that privacy projections attach to GPS and geolocation data.

In the 2012 case of United States v. Jones, the SCOTUS found that attaching a GPS device to the bottom of a car, without a warrant, constituted an unlawful search under the 4th amendment.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Samuel Alito noted, “Repeated visits to a church, a gym, a bar, or a bookie tell a story not told by any single visit, as does one’s not visiting any of these places over the course of a month. The sequence of a person’s movements can reveal still more; a single trip to a gynecologist’s office tells little about a woman, but that trip followed a few weeks later by a visit to a baby supply store tells a different story.”

Two years later, in Riley v. California, the Court found that police cannot search the contents of a cell phone without a warrant, particularly keying in on the phone’s location history stored as privacy-protected personal information.

In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the SCOTUS found privacy rights in geolocational cell site location information (CSLI). In that case, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that a legitimate expectation of privacy exists in CSLI records. He said, “Time-stamped data provides an intimate window into a person’s life, revealing not only his particular movements, but through them his familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations.”

Every case is fact-specific. As these issues get raised, the SCOTUS geolocation trilogy will remain at the core of the parties’ arguments. Enter: RaceDayQuads (RDQ) v. FAA.

The Case You May Not Have Heard About

RDQ v. FAA could potentially be one of the biggest cases in the geolocation tracking arena. This ongoing litigation specifically addresses the Federal Aviation Administration’s Remote Identification (RID) rule for drones, but could have broader implications for geo-tracking more generally.

The FAA launched the final RID rule in early January 2021, after two years of drafting, public comments and review. It creates a new Part 89 in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations that requires U.S.-operated small drones to beam out a “digital license plate” that other airspace users and the public writ large can receive. (This has been covered in Inside GNSS’s sister magazine Inside Unmanned Systems December 2020.)

The drone digital license plate will include the geolocational data of the drone and the pilot. Law enforcement and security agencies can access this information, and triangulate it with the FAA drone registration database, without a warrant. This would make drones in the U.S. trackable, in real-time, with precise locational data.

RDQ, a quadrotor drone shop, is challenging alleged irregularities in the rulemaking process as well as some substantive portions of the rule. RDQ alleges, among other things, that the RID rule equates to persistent GPS tracking in violation of the 4th Amendment.

One of RDQ’s counsel, Kathy Yodice of Washington D.C.-based Yodice Associates, an instrument-rated pilot and former FAA prosecutor with over 35 years representing clients in the aviation industry elaborated, “We understand and agree that the remote identification of drones is conceptually necessary for the safety and security of the airspace and our freedom to operate within it. But we are pressing the FAA to do this right.” She continued, “That means doing it without violating the law and without compromising our Constitutional rights.”

The FAA and its legal team have taken the position that the tracking enabled by the rule does not equate to an unreasonable search insofar as there is no privacy right in the movement of planes in the air and that the installation of a tracking device in and of itself does not violate privacy. Regardless, they say, the special needs of public safety and national security otherwise legally justify the rule.

The Association of Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) has joined in the case, with the court’s permission, with its own “friend of the court” brief, in support of the FAA’s position.

Not surprisingly, all the legal filings are replete with mentions of Jones, Riley and Carpenter.

Mark McKinnon, an attorney in the DC law firm of Fox Rothschild, predicted, “With regard to the geolocation issue, at the end of the day, I don’t think the plaintiffs will prevail on the Fourth Amendment issue. Aviation is a unique industry that has always had a higher level of government control, and the FAA’s control of aircraft in flight is far more comprehensive than the government’s control over cars on the road,” he said.

He continued, “Nearly 80 years ago, Supreme Court Justice Jackson described the federal government’s crucial role in aviation safety when he said, ‘Planes do not wander about in the sky like vagrant clouds. They move only by federal permission, subject to federal inspection, in the hands of federally certified personnel and under an intricate system of federal commands…Its (aircraft’s) privileges, rights, and protection, so far as transit is concerned, it owes to the Federal Government alone…’ That’s a pretty high bar.”

Oral arguments are scheduled for December 15th in D.C.’s U.S. District Court of Appeals. A decision should likely follow early in the new year.

The Feds Remain Largely Quiet

On the federal front, there’s little movement to protect geolocational privacy.

As an outlier, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has pursued geolocational data use without consumer consent as an unfair and deceptive practice under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act.

In 2017 the FTC went after Uber for the misuse of its “God View” which continuously geo-tracks all Uber users as part of the larger Uber rideshare app. This feature was allegedly used to track journalists who were vocally critical of the company.

Other than the FTC, the federal government, including Congress, has kept a relatively low profile on geolocational privacy since 2019, with a short burst of activity in the preceding years.

In appropriations acts between 2015 and 2019, Congress precluded the Department of Transportation from making any rules for private passenger motor vehicles that would require GPS tracking, without “full and appropriate consideration” of privacy concerns.” There has been no similar action in the past two years.

Similarly, a small cluster of bills in the 2017-2018 timeframe targeted GPS tracking. In 2017, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) floated the Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act (GPS Act), which went nowhere.

This wide-ranging legislation would have created a Foreign Intelligence and Surveillance Act (FISA)-like process for the government to obtain warrants for geolocation data. On the commercial side, it would have required customer consent before businesses could transfer their geolocational data to third parties.

Two bills followed in 2018 but likewise hit the floor. Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) introduced a Customer Online Notification for Stopping Edge-provider Network Transgressions Act (the CONSENT Act, S. 2639). It would have mandated the FTC to issue regulations relating to the sale of geolocation information and require consumer consent as a condition of the sale.

A Wyden-proposed Consumer Data Protection Act also never made it out of draft. Based on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which provides expansive rights to individuals to control how their personal data is collected and processed and puts the onus on data controllers and processors to protect such data, this one would have broadly protected “any information, regardless of how the information is collected, inferred, or obtained that is reasonably linkable to a specific consumer or consumer device.”

McKinnon surmised that Congress has been slow to act on protecting geolocation data because it is a valuable commodity that is widely used by companies for their own benefit or to sell to third parties.

Smartphone applications can collect and share consumer personal information with others, including geolocational information. Statistica reports that more than 109 billion apps were downloaded solely from the Google Play Store alone in 2020, and projects that by 2025, consumers will download 187 billion mobile apps from it.

Related data sales are big business. McKinsey and Company estimated that the digital advertising industry spent about $152 billion on third-party data this year.

According to McKinnon, geolocational privacy has also not struck a chord with the general public. “The momentum in favor of federal legislative action is just too low to counter those who resist it,” he said.

The States Lead the Charge

On the other hand, the states have been busy mixing geolocational privacy into their comprehensive state privacy legislation and consumer privacy laws.

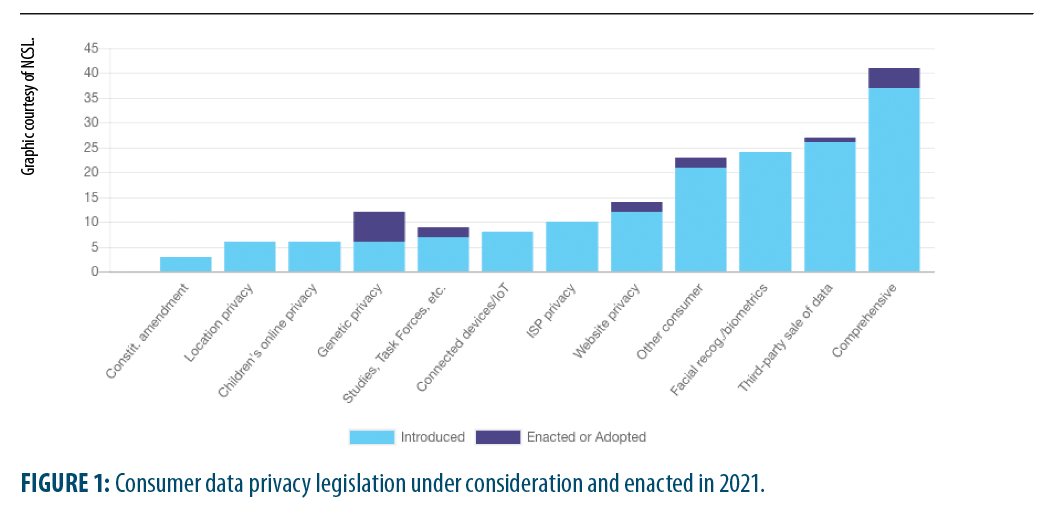

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) reports that in 2021, at least 38 states introduced more than 160 consumer privacy related bills, compared to 30 states in 2020 and 25 in 2019.

NCSL explained that comprehensive privacy legislation, introduced in the majority of these states, would broadly regulate the collection, use and disclosure of personal information and provide specific consumer rights with regard to it vis-a-vis businesses.

The 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) remains perhaps one of the broadest acts of its kind. This GDPR-inspired law grants extensive consumer rights relating to business’ collection and sale of their personal information. The CCPA’s definition of personal information includes geolocation data. Importantly, it grants a private right of action for breach. See sidebar.

In November 2020, California voters approved the California Privacy Rights and Enforcement Act (CPRA), effective January 1, 2023. It modifies the CCPA in an even more consumer-friendly way.

Among other things, the CPRA requires businesses to delete personal information when it is “no longer necessary” (undefined), correct inaccurate personal data and ensure third parties that receive personal information comply with the CCPA. It also expands liability to exposure of email addresses when combined with security questions and triples fines for breaching the data protections for minors.

In 2021, Virginia and Colorado were the second and third states to enact comprehensive consumer data privacy laws similar to the CCPA. The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) includes geolocation data in its definition of “sensitive data,” a separate category of personal data. The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) does not.

In 2021 alone, twenty-five states introduced, but did not pass, similar comprehensive privacy legislation. (See ncsl.org for a comprehensive list of state consumer privacy legislation.)

Watch Who’s Watching

When it comes to geolocational privacy, individual consent appears to be the coin of the realm.

Businesses should continue paying close attention to these developments. While the feds sit back and watch, the states are increasingly opting to provide consumers with privacy protections, including for geolocation. Some have opened the door to private causes of action for breach.

Government officials should also continue to monitor these state trends, as well as the potential resurrection of the GPS Act or similar legislation and how the D.C. court handles the geo-tracking issues in RDQ v. FAA.