Assessing the risk to GNSS and what could happen if we fail to act.

In many situations, the biggest threat is not the biggest risk. Failure to understand that and focusing on what appears to be the most pressing concern can lead to disaster.

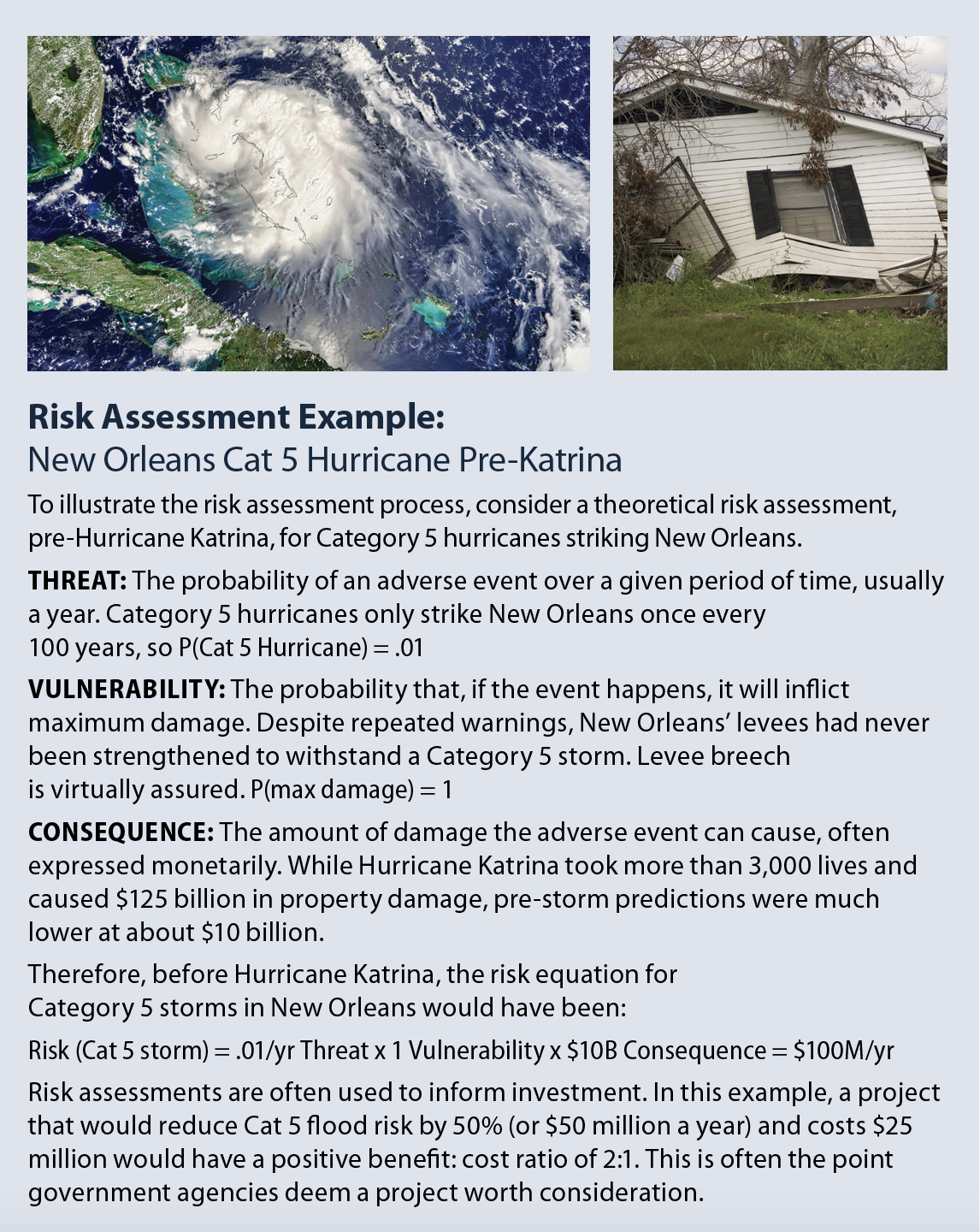

A classic example is flood preparedness in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina.

The biggest flood threat to the city has always been frequent intense rains from tropical and other storms. These often overwhelm the city’s stormwater management system. Streets and low-lying areas typically flood for a few hours, though sometimes it takes a day or more for the system’s pumps and drains to catch up. This happens so frequently it has become a fact of life. Residents have adapted by avoiding low areas and protecting their property as much as possible.

Yet, New Orleans’ biggest flood risk has always been a Category 5 Hurricane overtopping and destroying levees. While these storms only strike once every hundred years, their impact is devastating.

Before Katrina, New Orleans had guarded against its greatest flood threat, but not its greatest risk. When Katrina struck, that error cost 3,000 lives and $125 billion in property damage.

PNT Threats and Risks

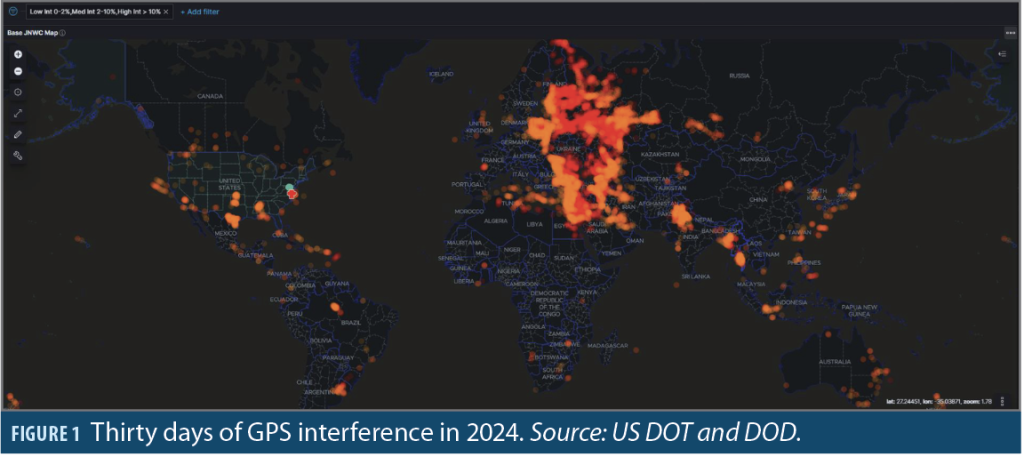

Localized GPS jamming and spoofing is the biggest threat to PNT services in America and Europe. Local and regional jamming and spoofing has become a fact of life and users are adapting by altering their behavior and, in some cases, upgrading equipment.

The biggest risk to PNT services is by most reckonings some form of long-term GNSS denial. Not the widespread, relatively low impact interference seen today. Yet, it’s been a challenge for Western governments to act to avoid a Katrina-like PNT disaster spread across multiple continents, a disaster it will take decades or more to recover from.

Risk Assessment

Structured risk assessments are one way to help leaders and their support staff focus on these kinds of issues.

At a high level, most methodologies assess risk from a potential adverse event as the product of threat: the probability of the adverse event; vulnerability, or the degree the impacted system or population is likely to suffer damage; and consequence, which is the amount of damage likely to occur if no mitigations are in place. Expressed as an equation:

The risk equation for potential malicious acts is slightly more complex. Threat is defined as the probability a bad actor can commit the act (capability) multiplied by the probability the bad actor will actually carry out the act (intent). This makes the risk equation for malicious acts:

Risk Assessment Challenges

Barriers to risk assessment include:

Estimating consequences. A significant obstacle to analyzing larger potential events is the difficulty of predicting consequences. For example, the pre-Katrina estimate of potential storm damage was less than 10% of what actually occurred.

Widespread, long-term GNSS denial is a much larger potential event and estimating consequence is much more problematic.

A good example of this is a 2019 study sponsored by the U.S. government examining the economic impact of losing GPS. It found an outage would cost the national economy $1 billion per day. While, at first glance, that seems a large number, it represented less than a 1.7% reduction in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is a very low consequence for a technological utility described by a member of the U.S. National Security Council as “a single point of failure” for the nation. By comparison (though admittedly not entirely analogous), a 2021 power outage in Texas cost $28 billion a day and 57 lives over a week.

It may not be possible to accurately predict and quantify the damage major societal disruptions cause. Multiple types of impacts, the interconnectedness of infrastructures, and the variety of human responses are highly complex and may be unknowable.

Non-quantifiable consequences. The biggest challenge, perhaps, is many impactful consequences can’t be quantified. What cost can be assigned to a government collapsing, to a nation being coerced, or the loss of prestige and influence with other nations?

These challenges might make risk assessment seem not worth it, but it is. The more impactful the potential outcomes, the more important it is for leaders to take a deliberate, thoughtful approach.

PNT Risk: Long Term GNSS Denial

The risk of long term GNSS denial is such a case. While good quantitative data may not be available or very difficult to obtain, there are things we know about the different elements of this risk equation. These help tell an impactful story and should inform decision-making.

Threat: Various possible adverse events can result in GNSS not being available to Western nations for extended periods or indefinitely. They include:

Severe Solar Activity: Researchers predict powerful solar events that can disrupt signals for days or destroy satellites occur once every 200 to 300 years. While these events are very low probability, the probability is greater than zero.

Electronic Warfare/ Cyber: The West’s adversaries have impressive terrestrial electronic warfare and cyber capabilities and are demonstrating them every day. These capabilities are also being moved into spaces where they are even more impactful. The non-zero probability of long-term GNSS denial to the West as the result of heightened world tensions, an autocrat’s whim, or open conflict amongst world powers must be considered.

Kinetic+: Several nations have or are developing capabilities to damage or destroy GNSS satellites. Press reports about Russian space-based nuclear weapons, Chinese satellite proximity operations, directed energy weapons, and the like show these must be considered in the overall risk.

Western Weakness: In November 2021, while preparing to invade Ukraine, Russia destroyed one if its defunct satellites with a ground-based missile. The next day, state media claimed that if NATO crossed Russia’s “red line,” Moscow would shoot down all 32 GPS satellites and blind the alliance. This may or may not have influenced U.S. policy and subsequent actions. Shortly after Russia’s public statement, though, the U.S. administration announced it would not send certain types of aid to Ukraine to “avoid provoking a Russian invasion.” A continued lack of PNT resilience in the West opens the door to further attempts at coercion.

Vulnerability: Most Western nations have no systemic PNT alternatives and are vulnerable to the loss of GNSS. While some alternate timing and location capabilities are in place for some applications, widely available, easily adoptable alternatives are not. If access to GNSS was denied long term, the probability of significant damage is very high.

Consequence: The impact of long-term GNSS denial on Western nations would be severe. GNSS signals have been incorporated into virtually every infrastructure and most IT applications. Dependencies and linkages are so numerous, complex and intricate, a complete quantitative assessment of impacts is likely unattainable.

Qualitative consequences would almost certainly include severe economic disruption, civil unrest, and greatly reduced ability to field and support military operations—all contributing to domestic instability and enabling adversaries to dictate terms and otherwise influence events on the global stage.

What’s it Worth?

The threat of long-term GNSS denial to the West is greater than zero. Deciding how much greater is a matter of subjective judgement that will vary from person to person depending on their knowledge, background and biases. Yet, all must agree the probability must be considered.

Vulnerability is also a subjective and difficult judgement. How do we estimate the degree infrastructure, individual users, security forces and economies, are already protected? Is the West 90% vulnerable? Perhaps 80%? It is another unknowable number, but thinking about it and testing some hypotheses is important.

Consequence may be the most difficult element of the equation. What are the monetary and non-monetary costs of major societal disruptions? Are there meaningful ways to express them?

Perhaps a better way to look at the public policy question is to ask “what’s it worth?” How much are we willing to spend to reduce this risk? How should we spend it to get the maximum reduction?

Some companies say they can provide a national terrestrial PNT system to complement and backup GPS for less than $90 million a year. Presumably, the government could then better encourage and, perhaps in some cases, mandate greater resilience. What would the risk reduction be? Is it worth the cost?

Mitigation: No silver bullet

It is never possible to eliminate risk, but there are ways to reduce it. Users can purchase better equipment and access alternative sources of time and location when able. Companies can better understand the criticality of PNT, their use of GNSS, and try to improve resilience.

At the national level, we all must help leaders understand PNT is essential. Over-relying on GNSS poses unacceptable risk, setting the stage for disaster.

A former boss of mine once said, “Good public policy is hard work…but only if you do it.” We need to get busy and do it.