Recent bipartisan legislation aims to make satellite communication and PNT services more available to farmers.

Legislation that nudges the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to do more to make satellite communication and PNT services available to rural America, particularly farmers, has sailed through the House and is awaiting committee action in the Senate.

The bipartisan legislation—something of a rarity these days—is House Resolution 1339, the Precision Agriculture Satellite Connectivity Act, sponsored by Rep. Robert E. Latta (R-Ohio) and cosponsored by Reps. Robin L. Kelly (D-Illinois), Troy Balderson (R-Ohio), Susie Lee (D-Nevada) and Rich W. Allen (R-Georgia).

After passing the House of Representatives in late April by a vote of 409-11, H.R. 1339 landed in the Senate in early May, where it awaits action by the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

Latta has been down this row before: In 2018, he was successful in getting wording included in the Farm Bill to create the Task Force for Meeting the Connectivity and Technology Needs of Precision Agriculture in the United States, operating under the FCC in conjunction with the Department of Agriculture.

As with the standalone legislation, it’s devoted to spurring deployment of broadband internet, with the goal of achieving reliable service on 95% of agricultural land by 2025. The task force, which includes agricultural producers, internet service providers, the satellite industry, precision agriculture equipment manufacturers and local and state government representatives, has been holding regular virtual meetings since its creation.

“I’ve talked with farmers throughout Ohio’s 5th congressional district that are utilizing advanced technologies to improve farm productivity and sustainability, and it’s making a big difference,” Latta said in 2018. “However, it’s clear that the agricultural community is at a disadvantage compared to other sectors because they are in rural areas that often have limited access to high-speed internet. It’s critical that we close the ‘digital divide’ to ensure that the agricultural community can fully utilize this cutting-edge technology.”

FCC Directions

Latta’s latest legislation isn’t controversial because it’s short, and essentially just directs the FCC to “review its rules regarding certain satellite communications services to determine if changes to its rules could promote precision agriculture.”

If the FCC determines there are rule changes that could be made to promote precision ag, “the FCC must develop recommendations and submit them to Congress within 15 months of enactment,” according to the bill.

And that’s pretty much it, which probably explains its easy path through Congress. Underlying the bill, however, are a host of issues that lawmakers, particularly those who represent rural areas, want to address, namely the “digital divide” that separates areas well served with broadband connections and those without access; the need for satellite data to make farming more efficient; and regulation and federal approvals said to be slowing the roll of an industry that’s raring to go.

A House report on the bill describes it this way:

“Precision agriculture allows for the optimization of crop yield, water usage and soil sustainability. Unfortunately, many rural communities have little or no connectivity, thereby reducing the ability for many farmers to utilize precision agriculture. Additionally, there are Earth exploration and observation services authorized by the FCC that could promote precision agriculture. These satellite technologies offer the opportunity to expand the use of precision agriculture throughout the United States, and this legislation would require the FCC to evaluate its rules to see if there are changes that can be made to promote this deployment.”

Latta is interested in the legislation because his district is one of the largest agriculture regions in the state. While some farmers are using satellite connections and precision agriculture, others aren’t but would like to.

Two hearings were held in the House related to the issue, by the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Communications and Technology (chaired by Latta), although neither was specifically about the bill. The first, held in early February, was titled “Launching into the State of the Satellite Marketplace.” The second, held less than a week later, was “Liftoff: Unleashing Innovation in Satellite Communications Technologies.”

Transforming Industries, Including Ag

Tom Stroup, president of the Satellite Industry Association, testified at the first hearing on the importance of the satellite industry.

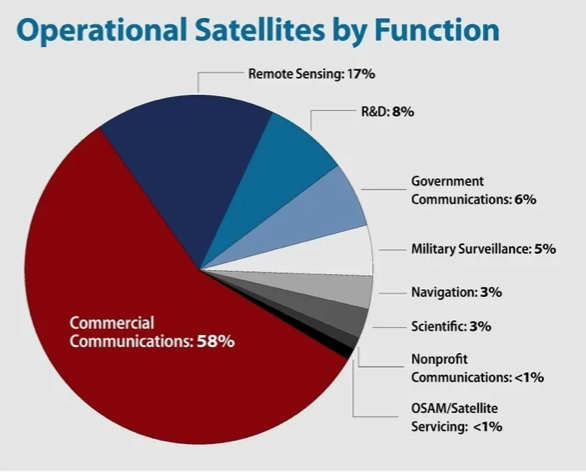

“We are at a time of explosive innovation in the space industry, with over 7,000 active satellites on orbit today and plans for tens of thousands more through the end of the decade,” he said.

“Satellites today provide anytime, anywhere global connectivity to consumers, utilities, supply chain logistics providers, the IoT [internet of things] community, cruise and other ships, airlines, and unmanned aerial vehicles. Soon, we will be living in a world where an autonomous car can update its operating system while driving anywhere in the world via a satellite link, spectators at a football game will be able to connect to satellite and use augmented reality to revisit plays on smart glasses in real-time, and connected sensors on infrastructure will be able to determine potential failures as well as directly deploy satellite-connected UAVs to inspect even the most remote sites.

“Geospatial satellite data has not only transformed environmental monitoring, but also provides essential business analytics from monitoring remote infrastructure to analyzing supply chain performance. When integrated with geolocation data provided by Global Positioning System, AI can be used in real time to redirect resources and optimize output.”

Stroup also said satellites are critical for disaster response as they aren’t susceptible to damage, can communicate with terminals and networks on the ground, and can employ synthetic aperture radar that can see through clouds and map damaged regions while storms are still under way.

And, as the title of Latta’s bill would suggest, satellites can aid farmers practicing precision agriculture.

“Satellite technology is transforming agriculture across America. Satellite broadband, for instance, enables remote farms with livestock sensors, soil monitors and autonomous farming equipment in rural America, far beyond where terrestrial wireless and wireline can reach or make economic sense to deploy,” Stroup said. “Precision GPS technologies allow farmers to increase crop yield by optimizing use of fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, and applying site-specific treatments to fields. Earth imaging satellites provide regular high-resolution imagery that allows farmers to determine when to plant, water or fertilize crops and can be used to provide crop yield estimates and monitor global food security. Satellite advances in weather forecasting help farmers prepare for drought, floods and other adverse weather conditions.”

Latta introduced his bill after those hearings, highlighting the need for reliable, fast internet for broad swaths of the economy.

“Farmers in rural Ohio also know that broadband connections are essential to their operations,” he said on the House floor. “After all, it helps deploy technologies that increase their productivity, produce higher yields and minimize operating costs. Today’s smart agriculture technology from autonomous tractors and distributed soil sensors rely on internet connections to share data. In fact, farmers use information in real time to make smarter decisions on how to optimize inputs in whether and when to plant and harvest. And when terrestrial or cellular networks are not available, satellite broadband steps in to make these technologies work.”

Latta noted Earth observation satellites also produce data useful for farmers, as they “help identify visual trends that need immediate attention.”

Dr. Simerjeet Virk, an assistant professor and extension precision agriculture specialist for the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at the University of Georgia-Tifton Campus, and a member of the International Society of Precision Agriculture, said connectivity continues to become more and more important for farmers.

“It’s not me taking a flash drive anymore to a tractor or sprayer or fertilizer spreader, it’s where I can sit in my office on my computer and I’m connected to all the displays in the tractor,” he said. “I can see in real-time on my phone which operator is doing what, and how much seeding they are applying.”

GPS accuracy with corrections has also improved immensely, Virk said. “We’re not working in feet and meters anymore, we’re working in sub-centimeter, sub-inch, plant-by-plant application,” he said. As those systems get more precise, farmers also need them to be repeatable, meaning they need access all the time.

“We still have a lot of areas where we don’t have connectivity,” he said. “Or, there are different ways of getting the GPS accuracy and a lot of times you have to be out there for a longer time before you can utilize the high accuracy systems. I think that’s where some of this [legislative push] is coming back to, is improving the overall connectivity between the systems.”

Possible Outcomes and Challenges

So, what are the problems and what could the FCC do about them?

Witnesses at the hearings had some ideas. Julie Zoller, head of global regulatory affairs for Amazon’s Project Kuiper, said the growth of the satellite industry is “straining the ability of regulators to process a wave of license applications under the current rules.” Kuiper is a $10 billion-plus planned constellation of 3,236 satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), with the first service expected to begin in late 2024.

Zoller did praise the FCC because it has “proposed rules that would provide more spectrum for non-geostationary satellite orbit [NGSO] services and greater clarity for spectrum sharing between NGSO systems. Not only will this ensure American leadership, but it will bring the benefits of investment, innovation and choice to customers.”

And, as her title would indicate, Zoller has to keep an eye on international rules as well. “Outdated rules are also a challenge outside of the United States. Many of the International Telecommunication Union rules for NGSO satellites favor incumbent technologies,” she said. “At the World Radiocommunication Conference later this year, it is essential that the U.S. set forth key priorities to ensure that the rules for NGSO systems, and satellites more generally, support the success of this U.S.-led technology and service.”

The WRC, held every three to four years to review or revise the international treaty governing the use of radio-frequency spectrum and geostationary and NGOS satellite orbits, is scheduled for this fall in Dubai. This year’s conference will consider a range of issues aimed at facilitating new terrestrial and space-based connection technologies, “including spectrum for next-generation mobile broadband systems, satellites, maritime and aeronautical services, and scientific applications,” according to the FCC.

Defense Issues

There’s more to the issue than just commercial interests, said Kari A. Bingen, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington think tank, also testifying at the first hearing.

Bingen said building and launching satellites has gotten much cheaper and faster—satellites that were once the size of buses are now the size of “microwaves and loaves of bread” and can be produced in months or even days, not years.

These changes have drawn more interest from governments, Bingen said, as more than 85 nations are now operating in space, far beyond the longstanding space powers. China is pursuing the most expansive program, she said, aiming to take the space race lead by 2049.

“In our 2022 report, we highlighted China’s increasingly robust space capabilities, including advanced positioning, navigation and timing; satellite communications; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and missile warning; in-space logistics; and space situational awareness,” Bingen said. “China’s proficiency in areas like space-based imagery capabilities, paired with its advances in AI, means that it will be able to detect and locate U.S. forces from space in near-real time. China also has a robust arsenal of counterspace capabilities able to target U.S. space assets, ranging from cyberattacks, to reversible GPS and SATCOM jammers, to direct ascent anti-satellite missiles and co-orbital satellites that kinetically impact their targets.”

The use of those counterspace weapons isn’t hypothetical, she noted, as Russia targeted GPS, Starlink and Viasat in Ukraine with jamming and cyberattacks. “As space capabilities increasingly show their value to national security, especially in areas like imagery and communications, adversaries will seek to deny their use,” Bingen said.

On the commercial side, at least, Bingen said there are some things the FCC and other agencies could do, namely “strike the appropriate balance between burdensome regulation and market development.”

For instance, in the United States, space operators go to the FCC for spectrum, the FAA for launch, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for commercial remote sensing licenses, and the State Department and Commerce Department for issues relating to exportability.

Quoting the market analysis firm Quilty Analytics, she said, “The most difficult aspect of building a [LEO] broadband system is acquiring the spectrum, not building and launching satellites…navigating an onerous regulatory process—while also facing narrow profit margins and unforgiving business models of LEO broadband systems—can make it impossible for all but the largest, most well-resourced companies to obtain licenses.”

Pushing Forward

As for the latest legislative push, in the end, the FCC may discover it can’t do anything more to foster precision agriculture or other satellite broadband or PNT uses. Latta said he’ll keep trying.

“I’m committed to ensuring our farmers have the tools needed at their disposal to help increase productivity while minimizing costs,” he said. “This legislation is a good step forward in that mission.”