Though the FCC approved Ligado Networks’ request to use satellite frequencies to support terrestrial 5G, opposition to the move remains firm as everyone waits to see what kind of measures are included in the final decision to protect GPS from interference.

Whether or not GPS really will a actually be protected remains far from clear. Opponents are convinced Ligado’s plans pose a threat to GPS despite the assurances in FCC press releases that the final order will incorporate “stringent conditions to ensure that incumbents would not experience harmful interference.”

They have reason to be doubtful.

Protections?

Some of the key conditions touted in the FCC releases are not new. Ligado several years ago proposed creating a 23 MHz buffer zone or “guard band” between Ligado and GPS frequencies and cutting the Ligado base station power to 9.8 dBW. These measures were taken into account during extensive testing by the Department of Transportation (DOT) in 2016. That testing showed Ligado’s revised plan still posed an interference risk to GPS receivers.

“There is reason for significant concern that the FCC’s approval of the Ligado application could lead to widespread interruptions in essential GPS-dependent services,” said Diana Furchtgott-Roth, DOT’s deputy assistant secretary for research and technology in a statement.

Just reducing power, for example, does not address interference because that depends on a number of other factors.

“A higher density of base stations operating at lower power levels in an area could create the same level of interference as a more limited number of base stations with higher power,” said GPS receiver manufacturer Trimble in a filing posted April 21 by the FCC.

“They (the FCC and Ligado) make a stunningly erroneous claim that by using lower power transmitters, the problem is solved,” said Logan Scott, a GPS signal expert and a consultant specializing in radio frequency signal processing and waveform design for communications, navigation, and other systems. “If they would talk to an engineer, they would learn that cellular service provisioning is a game of flux density. As you lower the transmit power, you need more cellular base stations. To use an analogy from my backyard, I can install one high-flow sprinkler head to cover the entire yard or a bunch of low-flow heads, each covering a small portion. Either way, the grass does not care about anything other than inches of water and we are going to get wet if we run across the yard. Ligado’s core argument that low power will cause no harm is equally wet.”

Garmin, which also makes GPS receivers, pointed out in another new filing that Ligado has failed for years to provide any details about how it intended to deploy its ground structures despite repeated requests.

“A terrestrial wireless broadband system embodies much more than transmit power, and its operation is largely dependent on other deployment parameters such as tower spacing (ISD), antenna height, antenna downtilt, and antenna polarization,” Garmin wrote. “A proposed power level of 9.8 dBW alone is insufficient to fully specify a system that will protect GPS.”

Army Strong

The Defense Department reiterated its opposition in a statement to Inside GNSS Tuesday.

“Each American relies on GPS each day for many things like E-911 to locate citizens in need of emergency assistance, our financial system, to order and receive shipments, to travel for work and leisure, and even use in cellphones,” the statement said.” The military relies on GPS each day for all those reasons as well and additionally to coordinate tactical operations, launch spacecraft, track national security threats, and deliver precision munitions — and this decision by the FCC will put the military and everyone’s use of GPS at risk. That’s why the Department and eight other federal agencies are strongly opposed to this proposal and have asked for denial.”

Whose Yardstick?

One of the key issues is defining what constitutes interference and Ligado has been seeking to change the yardstick.

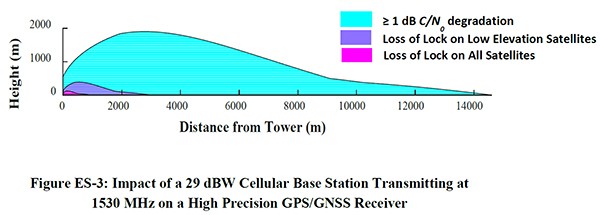

The GPS community relies on an internationally accepted criterion of a one-decibel (1 dB) degradation of C/N0, the carrier-to-noise power density ratio. This is also described as an Interference Protection Criterion or IPC.

That mouthful of terminology refers to the strength of the signal relative to the surrounding noise. Since the signal strength can naturally change a bit (the signals are coming from moving satellites, for example) and the surrounding noise can vary, GPS experts use this combined, easy-to-measure criterion to determine how noisy things can get and still have receivers work reliably. The IPC includes a bit of margin to allow for the natural fluctuations.

Ligado, however, wants to define interference as when things actually go wrong. According to Ligado interference only occurs when there is a change in key performance indicators — that is when the positioning and timing accuracy as experienced by the user are thrown off. Since interference must only be addressed when something is not working there is arguably little or no safety margin.

“Not only does (the 1 dB standard) have a long and well-established history in both international and domestic regulatory proceedings of protecting GNSS operations from harmful interference,” wrote Trimble, “but it also provides the most readily identifiable and predictable metric that will ensure a harmful interference level is prevented. It is the only reliable mechanism to ensure the adequate protection of GNSS receivers. Alternative metrics, such as key performance indicators, are administratively impractical given the wide diversity of GNSS receivers and applications, and only reveal problems after harmful interference has already occurred, leaving GPS users with inaccurate or misleading information.”

Industry Group

The GPS Innovation Alliance (GPSIA), whose members comprise a number of receiver manufacturers, expressed deep disappointment that the FCC appears to have ignored “the well-documented views of the expert agencies charged with preserving the integrity of GPS, specifically on the critical issue of what constitutes harmful interference to users of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), said J. David Grossman, GPSIA’s executive director.

The 1 dB Standard for radiofrequency-based services is critical for GNSS, said Grossman. “GPSIA has consistently advocated for adoption of the 1 dB Standard as the only reliable mechanism that provides the predictability and certainty to ensure the continuation of the GPS success story, with the support of the Department of Defense, the Department of Transportation and numerous other federal agencies.”

That reliability is vital as GPS is used for all forms of transportation as well as modern emergency response systems, said Furchtgott-Roth. It is essential to effectively guiding police, fire, and other rescue vehicles to where they are needed.

“GPS is the invisible utility we all take for granted, and the Federal government has a duty to public safety to ensure that GPS remains accurate and available,” said Furchtgott-Roth.