Nominal architecture of a GPS/Galileo PRS receiver

Nominal architecture of a GPS/Galileo PRS receiverThe United States and the European Union are talking about how U.S. agencies might use the secure signal planned for Galileo to better fulfill their various responsibilities.

The United States and the European Union are talking about how U.S. agencies might use the secure signal planned for Galileo to better fulfill their various responsibilities.

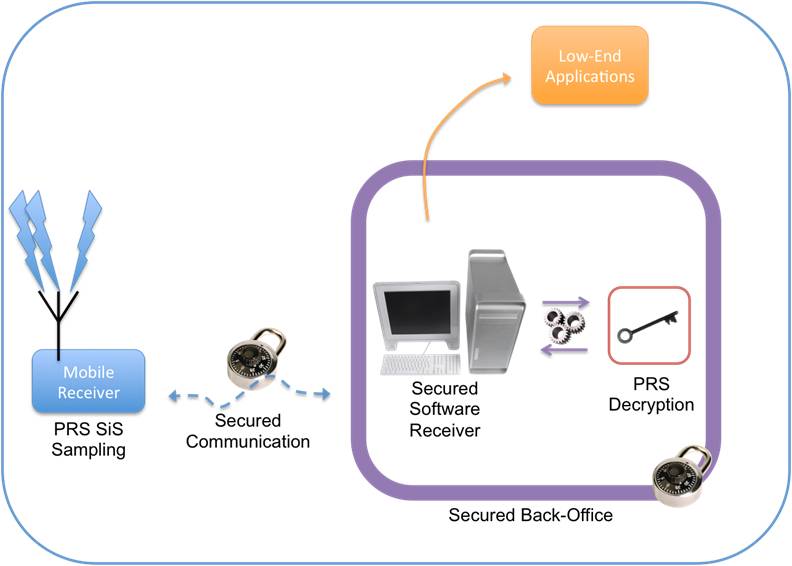

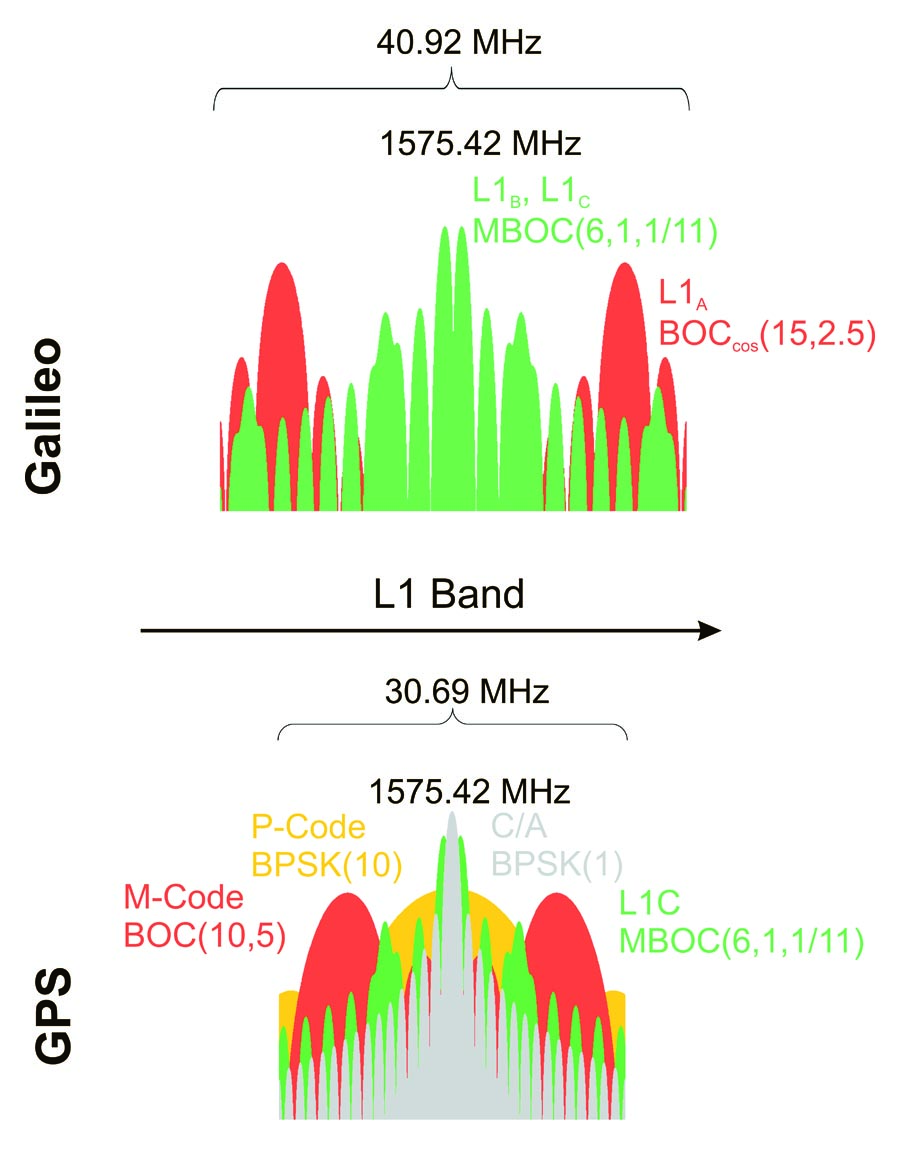

Informal discussions on using the Public Regulated Service, or PRS, began after the European Commission released guidelines for accessing the service last fall. PRS will provide an encrypted signal that is intended to support police, emergency services and critical infrastructure. Use of this signal, which is supposed to be more robust, will be limited to governments and other specifically approved entities.

Though the commercial sector has long incorporated multiple GNSS systems into its receivers, the option to tap non-GPS constellations for positioning and timing service is relatively new for U.S. government officials and programs. The GNSS policies issued by the White House in 1996 and 2006 addressed the international aspects of satellite navigation but focused on the goal of GPS preeminence. In its 2010 National Space Policy the Obama Administration expanded the scope of potential GNSS cooperation, opening the door for the U.S. government to utilize non-GPS systems.

“For the very first time it said that we can use other nation’s space-based PNT services for our federal government needs — assuming that it meets our standards,” said Tony Russo, the director of the National Coordination Office for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing.

Last September the European Parliament passed a resolution setting broad rules for the use of the PRS by both EU and non-EU members. That triggered discussions within U.S. federal agencies on how they might employ the service.

“Part of the Executive Steering Group and [National Executive Committee for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing] has been working with the departments and agencies on how we might incorporate [PRS] for enhancing government capabilities — because that is something we’re not providing now,” said Russo.

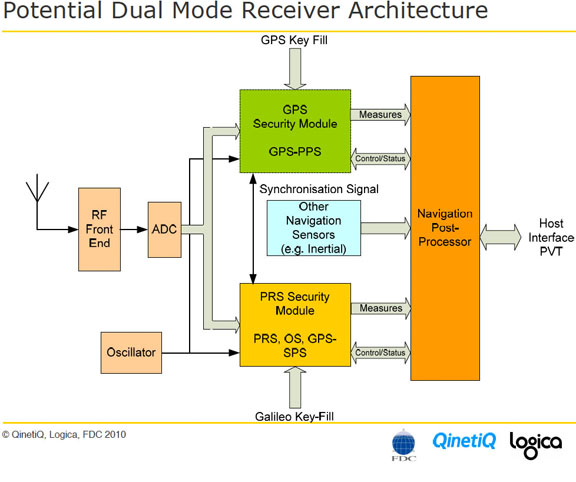

“We have our encrypted military signal and then we have our open civil signal — but very little civil agency use of that encrypted military signal. There might be a good opening here if there was a civil encrypted signal that people could use for highly secure applications — maybe some DHS kind of homeland security things,” he added.

State Department Heads U.S. Reps

With the State Department taking the lead, the United States opened informal talks with the European Commission, asking a number of questions about the signal and how things might work. The U.S. military is in discussions about PRS as well, said Russo.

The conversation is at an early stage and there is no working group or deadline of any kind. It is too soon to gauge the level of interest among U.S. officials, experts said.

“No one (in the U.S. government) has expressed a firm interest in it (PRS),” said a source familiar with the discussions. “I think people are still trying to assess ‘Would this really be something that we would want to sign an agreement for, and what would that mean?’ ”

Any deal to use the encrypted Galileo signal would come with some strings. An agreement would have to be worked out in advance, and the EU will control not only access to the signal but the production of receivers and their export. The European policy precludes sending receivers to countries where there is no PRS agreement. It does not however, limit receiver manufacturing to the EU. According to the resolution, international agreements “could include the manufacturing, under specific conditions, of PRS receivers, at the exclusion of security modules.”

The United States would also likely be asked to compensate the European Union for the use of PRS.

“They would get something back for it I am sure,” said Russo, “because that is part of the way they’re funding their system. So we would pay a fee like any other user or we would become a partner . . . just like you would be for a military alliance — you would do that on the civil side as well.”

It’s Complicated

Should a deal be worked out, as with all other users tapping PRS, the United States would need to set up a “Competent PRS Authority” to manage its use.

“The way the policy is set up the commission will administer the signal and the service, and they’ll set the terms and conditions, and they’ll set the technical parameters,” said the source, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Then it will be up to each member state of the EU to then give access to those entities within their jurisdiction to the PRS signal consistent with the overall PRS policy.”

“So, you don’t go directly to the commission and sign an agreement for access to PRS — that will be between the member state and the Commission, and the member state will give access to whomever they want to, consistent with the overall policy.”

That agency would need staff and resources, the source confirmed.

“You are going have to have staff and you are going to have to maintain a database,” said the source. “Essentially it will be providing a service. You will probably have to have an office for PRS access in one agency.”

A deal is a good ways off, though, because the PRS signal — which is not expected to be available before 2014 — is not fully defined, although successful transmissions of PRS test signals have occurred.

“In terms of the technically defined the parameters of signal, how the service would work and what the concept of operations is — those things are just not defined enough for us to make any kind of decision,” explained Russo. “So we have a general interest in using that capability in the future, but we have not made any commitments and we’re not close to making any commitments. But we continue to be interested as a result of the president’s policy.”

The PRS talks are taking place within the broader context of the United States’ overall international strategy. That strategy, which is classified, is reviewed annually said Russo, and updated as necessary.

Other activities under that strategy include ongoing discussions with the Russians about using GLONASS.

“We are talking to the Russians,” said Russo. “I know the aviation community has been talking about multi-GNSS receivers for aviation purposes. But again I don’t think they have reached any kind of deal or anything.”

Dee Ann Divis is an editor at the Washington Examiner in Washington D.C. She writes the Washington View column for Inside GNSS.