Techniques to avoid aircraft collisions took center stage as aviation experts met in Washington this week to continue hammering out the standards essential to integrating unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) into the nation’s skies.

The standards are being developed by RTCA Special Committee 228 (SC-228), one of the family of committees operating through RTCA, Inc., which develops consensus standard for aviation, which are then adopted and put into real-world practice by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Techniques to avoid aircraft collisions took center stage as aviation experts met in Washington this week to continue hammering out the standards essential to integrating unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) into the nation’s skies.

The standards are being developed by RTCA Special Committee 228 (SC-228), one of the family of committees operating through RTCA, Inc., which develops consensus standard for aviation, which are then adopted and put into real-world practice by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

SC-228 has the narrow but crucial task of developing some of the initial standards for larger unmanned aerial systems (UAS) transiting through Class D airspace (from the surface to 2,500 feet or 760 meters above the ground), E (generally airspace extending from 1,200 feet or 370 above ground level up to but not including 18,000 feet or 5,500 meters), and G airspace (all airspace below 60,000 feet not otherwise classified as controlled).

The special committee is working on standards for detect-and-avoid technology, which is widely seen as crucial for UAS to be able to regularly use the national airspace, and for the communications that keep unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly called drones, linked with their remotely based pilots.

Although its mandate is limited, the committee’s decisions help set the foundation for later standards, making them particularly important. The committee is working to have its draft standards ready by 2015 so that they can be tested and finalized by 2016.

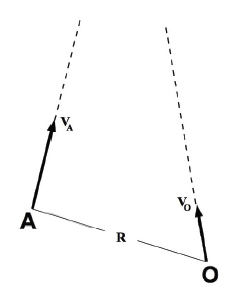

Detect and avoid breaks down into two parts — the standards for separation between aircraft and the measures to avoid collision when separation safety margins are breached. The committee is trying to reach consensus on standards for both parts and did announce agreement on a definition of “well clear” — the amount of distance needed to safely keep aircraft separated from obstacles, including other aircraft.

Well clear was defined as 35-second Tau with a horizontal miss distance (HMD) of 4,000 feet and a 700-foot vertical miss distance (VMD). This model was the best at minimizing the number of RAs or resolution advisories — the urgent flight instructions issued to avoid collisions.

Some concerns still remain about the operational implications of the new well clear parameters, a subject the working group said it plans to discuss in more detail.

Agreement was yet to be reached, however, on collision avoidance standards, which became the subject of a testy exchange.

Bridger Newman, an aviation safety and security specialist with the Airline Pilots Association (ALPA), questioned how collision avoidance was being handled in a key white paper.

“It seems like we’re just focusing on self separation,” Newman said. “That is not something ALPA will agree to.”

APLA wants to see unmanned systems equipped with a collision avoidance technology that effectively provides the same kind of safety margin enabled by the FAA’s Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System or TCAS. The pilots association is concerned that that margin is not being included in the detect-and-avoid standards being developed for UAS.

“TCAS took an awful lot of time (to develop),” Capt. Sean Cassidy, ALPA’s first vice president and national safety coordinator told Inside GNSS. “There was a tremendous amount of work on algorithms. But the net result has been spectacular when you consider the fact we haven’t had a midair collision.”

“If we want to have that same level of safety,” Cassidy, said, “we have to have that type of technology not only on board commercial aircraft but on board the other aircraft that are going to be occupying the same airspace.”

The current rules for aircraft do dictate when unmanned aircraft would need to carry to TCAS, Jim Williams told the group. Williams is the manager of the FAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Integration Office and the lead agency representative on the committee. Any aircraft that met the current criteria for TCAS would need to equip, he said.

“It is not our plan to change those rules to create blanket coverage for UAS,” Williams added.

Having SC-228 working on its own could result in conflicting standards that the FAA “will never adopt,” said one expert, who asked not to be identified so that they could speak freely.

Another RTCA committee, SC-147, is already responsible for standards for the next update of TCAS and the white paper says SC-228 will collaborate with SC-147, “on the development of a Collision Avoidance interoperability standard.” Working through SC-147 could avoid certifying a new standard and doing again the international coordination that makes it possible for planes can fly freely and safely between nations.

Cassidy underscored in an interview Inside GNSS that ALPA, a long time member of SC-228, would not support UAS standards that did not include some type of collision avoidance system that basically provides the same kind of safety margin as the onboard TCAS system.

Part of the disagreement, however, may be rooted in the wording of the white paper, which Williams described as “unfortunate.”

SC-228 co-chair George Ligler, an aviation consultant, said that good people were reading and interpreting the paper in different ways. He took on the task of working through the confusion and reporting back.