While a representative for a proposed broadband network assured attendees at a recent satellite navigation meeting that their telecom system could co-exist with the Global Positioning System, a panel of GPS experts raised new doubts about the broadband system and interference from its handsets.

While a representative for a proposed broadband network assured attendees at a recent satellite navigation meeting that their telecom system could co-exist with the Global Positioning System, a panel of GPS experts raised new doubts about the broadband system and interference from its handsets.

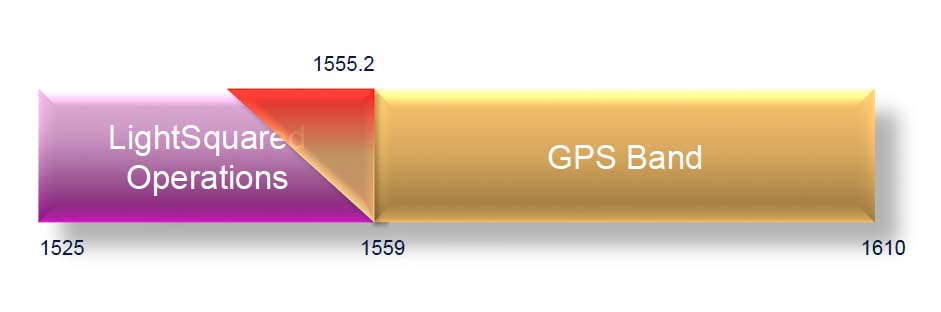

LightSquared has proposed a nationwide wireless broadband network with a backbone of more than 30,000 high-powered ground stations that would broadcast in the frequency band adjacent to that used by GPS. Given a conditional waiver to go ahead by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) this January, the Virginia company has been trying to work out interference issues with an increasingly alarmed navigation community and get the final go-ahead to deploy.

Testing on a wide variety of receivers earlier this year showed that signals from the terrestrial network, as originally proposed last fall, overloaded and/or interfered with nearly every kind of GPS receiver.

“It is one of the highest power signals you can have from a receiver perspective,” Trimble’s Bruce Peetz, told a packed room packed session at the Institute of Navigation’s GNSS 2011 conference in Portland.

The panelists summarized the results of the first round of testing — pointing out the adverse effects on GNSS receivers across the board.

The network is “incompatible with aviation GPS operations,” said Scott Burgett of Garmin International, and would trigger the “complete loss of GPS operations below 2,000 feet.” For wideband receivers, said Pat Fenton of Novatel, “it is pretty much a wipe-out.”

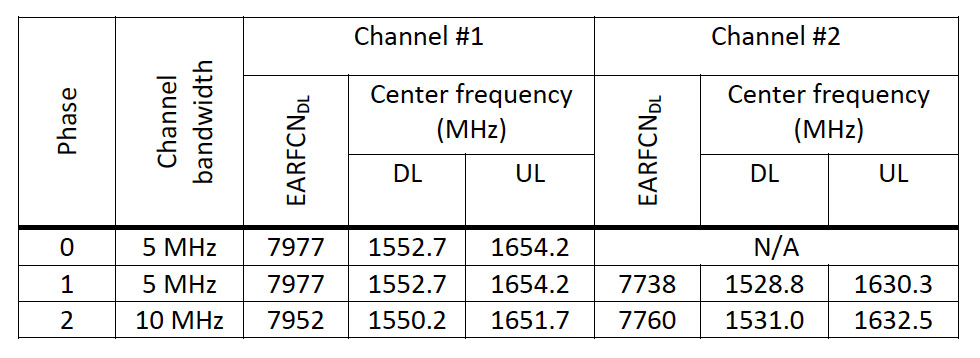

The tests, they noted, were conducted largely on the original LightSquared plan, which included upper and lower 10-megahertz bands in the 1525–1559 MHz portion of the spectrum just below that of GPS and other GNSS services. The firm has since offered to delay use of the upper 10 megahertz and limit the power of its transmissions, as measured on the ground, to no more than -30dbm at the start of the systems’ deployment. That would increase to -27dBm by January 1, 2015, and -24dBm by January 1, 2017.

The company had originally planned to use the two bands in a different order, explained LightSquared’s Executive Vice-President Martin Harriman, but it could switch things around and still move forward. The shift “gives us enough to get a number of years into our plan.”

That would help, agreed the GPS industry panelists, but they added it was not clear that it would solve the problem. For example, although the shift to the lower band would give aviation receivers a small positive margin while tracking a GPS satellite signal, the user equipment requires an additional six decibels in order to acquire the signals in the first place, said Burgett.

Moreover, members of the panel pointed out, LightSquared has not agreed to drop the upper 10-megahertz band on a permanent basis.

Missing altogether, several panelists noted, were tests results on LightSquared mobile handsets. Panel chairman Tom Stansell noted that the “specified out-of-band emissions [OOBE] for the handsets is about 8.6 dB above the noise floor, if you are two meters away.”

No tests have been conducted on LightSquared handsets, said Paul Galyean of John Deere, because, as yet, no such handsets are available. OOBE interference from the units, however, could be worse than the interference from the base stations. Analysis showed, Galyean said, that one handset at a one-meter distance, operating at the mask level permitted by the FCC, could cause 16 decibels of carrier-to-noise (C/N0) degradation. Fifty handsets within 50 meters could cause of C/N0 degradation amounting to 13dB.

Earlier in the day, LightSquared and JAVAD GNSS had announced the development of a new GPS receiver that uses the buffer created by dropping the upper 10 megahertz of LightSquared’s spectrum to avoid interference issues. Though Harriman said the technology would be available for license, GPS panel members said the new development did nothing for installed receivers.

“We must protect our legacy users — they have few options,” said CSR’s Greg Turetzky, who worked on the cellular phone tests

Disagreement arose earlier this year about what constituted acceptable degradation, but both Harriman and the GPS experts on the panel said that agreement had been effectively reached that the level was one decibel.

The audience had apparently reached consensus on a different point — that more time was needed for interference testing. The FCC recently acknowedged that more testing was needed. But the ION GNSS 2011 audience burst into applause when Galyean complained that the testing of the LightSquared system was far too rushed.

“When we got the testing charter from the FCC [Federal Communications Commission], we got a timeline that was, in my opinion absolutely ridiculous,” said Galyean, who participated in the technical working group set up to investigate the issue. “So, the NTIA [National Telecommunications and Information Administration] has now requested more testing . . . and given another ridiculously short timeline in which to do the testing. That schedule, completing the next round of testing by November 30, in my opinion is absurd.”