Ligado Networks is pushing spectrum regulators to make a decision on its request to allow satellite frequencies near the GPS band to also be used for terrestrial 5G networks.

To support their appeal for a wavier to the license—and perhaps boost the likelihood of a sooner-than-later response—the company is casting its plan as part of an on-going 5G controversy that needs to be resolved before a crucial fall negotiation. Moreover, Ligado is insisting that a decision is long overdo under legal requirements set out in Section 7 of the Communications Act.

What does all this add up to? That’s hard to say, at least in the near term. That urgent spectrum controversy is not about the mid-band frequencies Ligado is licensed to use. In fact it’s not about mid-band frequencies at all. As for Section 7, even though it has been in place since 1983, it’s so far been applied in an ad hoc manner—until now that is. Regulators are in the middle of crafting rules to implement the section and it is at least possible that the process may delay a response to Ligado’s request.

Background

Ligado is the successor company to LightSquared, which sought a license modification in 2010 to allow frequencies designated for satellite communications to be used for a high-powered, nationwide terrestrial network to serve the surging broadband market. Tests later showed that the network’s signals would overload the vast majority of GPS receivers. (A $2 billion lawsuit filed in December 2017 alleges that the interference problem was known before LightSquared made its request but was fraudulently concealed from LightSquared’s backers (see box, page 20).

After tests were completed in 2011 the results went to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), a Department of Commerce agency that coordinates government use of spectrum. In February 2012 the NTIA sent a letter to the Federal Communications Commission saying the GPS interference that would be caused by LightSquared’s network could not be mitigated and the FCC immediately put a hold on LightSquared’s request; the firm filed for bankruptcy shortly thereafter. LightSquared soon sued the federal government and a number of GPS firms and interest groups. The firm emerged from bankruptcy in 2015, dismissed or settled its lawsuits and adopted a new name and a new plan created to help address the GPS interference issues. More recently it’s been proposing that its L-band spectrum would be a highly useful component of the new wireless networks being built to the emerging and very promising 5G standards, which will ultimately enable wireless networks to handle far greater amounts of data at faster speeds.

Politics

Ligado has been stressing that a decision on its request needs to be made quickly if it is to add its spectrum to the national push to deploy 5G. In recent statements, including a June 26 FCC filing, the firm has insisted that the delay in approval of its request is anchored in Washington maneuvering and not the GPS interference issues that hamstrung the plans of its predecessor.

“For the past three-and-a-half years, Ligado Networks has worked with industry and government stakeholders on a plan that will finally unlock our lower mid-band spectrum for 5G. We have participated in testing, analysis, studies, workshops, reviews, and meetings, and time after time, we have accepted the burden to resolve concerns by modifying our plan. We have patiently waited for an FCC decision allowing our company to make additional investments that industries here in America so desperately need,” said Ligado Networks CEO Doug Smith in a June 25 statement. “But we can only wait so long—especially when we are no longer debating substance—technology led by the smartphone industry resolved that nearly a decade ago—but waiting because of politics. Industries in need of spectrum simply cannot wait any longer. Ligado cannot wait, and the U.S. will not win the 5G race by waiting.”

To help make the case that it’s being delayed by a political problem and not a technical one Ligado pointed to testimony by FCC Chairman Ajit Pai who told the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee on June 12 that the Department of Commerce “has been blocking our efforts at every single turn” to get more spectrum for 5G. The agency’s opposition, Pai said, could hamper the United States in negotiations expected at the World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC) to be held October 28 through November 22 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. Convened every four years, these vitally important WRC meetings are where nations hammer out what spectrum will be used for what purpose. The fortunes of companies, even entire industries, can turn on the decisions made there.

However, if one digs through the statements, testimony and filings it becomes clear that, while there has been an ongoing argument between the FCC and the Department of Commerce, and there is indeed concern it will impact U.S. efforts at the WRC, the matter at hand does not involve Ligado’s frequencies. The spat being discussed in the hearing had to do with spectrum in the 24 GHz band and whether broadband systems will interfere with atmospheric sensors used for weather and climate forecasting. Some of those sensors are in the neighboring 23.8 GHz band and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is part of Commerce, believes the impact could be severe.

Moreover, though quickly getting more spectrum for 5G is at the heart of the FCC’s 5G FAST Plan (for Facilitate America’s Superiority in 5G Technology) Ligado’s frequencies are not part of that either. The Commission held a 5G spectrum auction earlier this year for frequencies in the 28 GHz band. There are also plans to auction frequencies in other “high band” portions of the spectrum including frequencies in the 37 GHz, 39 GHz, and 47 GHz bands. Though the FCC has 5G-related plans for freeing up mid-band spectrum (the bandwidth neighborhood where GPS and Ligado spectrum reside) and low-band frequencies those efforts are focused on the 2.5 GHz, 3.5 GHz, and 3.7-4.2 GHz bands as well as the 600 MHz, 800 MHz, and 900 MHz bands. The FCC is also looking at the 3.1-3.55 GHz band at the direction of Congress.

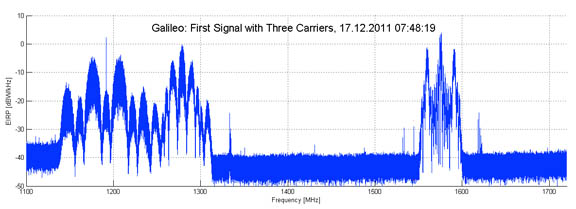

Ligado’s spectrum and potential spectrum allocation runs from 1564 to 1680 MHz (see box). That does not mean that the matter can not come up, only that the FCC is focused elsewhere and, in fact, has its plate more than full with other 5G matters.

Ligado is trying to put “5G pixie dust on GPS interference and make it go away,” Recon Analytics analyst Roger Entner told Communications Daily in June. “I don’t think the FCC is going to be swayed by that argument at all.”

12 miles or 1 milliwatt

In fact, the GPS interference issue has not gone away, said Brad Parkinson, the vice chair of the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board. “Many other organizations have filed opposition to this (Ligado’s proposal) and we in the past have gone on record in writing as unanimously recommending disapproval,” Parkinson told the board at their own June 6 meeting. “Nothing has changed.”

The PNT Advisory Board comprises the nation’s leading experts on satellite navigation. They provide independent advice on GPS-related policy, planning, program management, and funding profiles to the National Executive Committee for Space-based PNT (the ExCom). The ExCom is a high-level, policy body with representatives from nine different agencies that coordinates GPS-related matters to ensure the system addresses national priorities as well as military requirements.

Parkinson presented an analysis to the board showing what it would take to protect the most sensitive GPS receivers under the current Ligado plan. Ligado has made some changes since 2015 including announcing in 2018 that it was cutting its initial transmitter power to 10 watts. Based on that information, and test results from the Department of Transportation’s Adjacent Band Compatibility (ABC) Assessment, Parkinson looked at the impact to the receivers used for high precision, high productivity applications such as precision agriculture, robotics, machine control, scientific applications—including sensitive weather probes—as well as commercial timing, survey and mapping. (Parkinson called the ABC tests “the only credible set to allow calculations.” Released in May 2018 the study showed the power levels that could be tolerated by 80 representative GPS receivers. It can be found at https://www.transportation.gov/pnt/global-positioning-systemgps-adjacent-band-compatibility-assessment)

During his presentation Parkinson noted that configuration of the Ligado network, which is critical to determining interference, remains unclear. Though asked more than once Ligado Executive Vice President Valerie Green provided little insight into how the network would be laid out when she spoke to the Board’s November 2017 meeting. Inside GNSS did reach out to Ligado for more information about its network, and any other details or comment the firm might offer for this story, but did not get a response.

At 10 watts Parkinson said that the towers for the network would have to be spaced 12 miles apart to protect the high precision GPS receivers in 90 percent of the covered region. That is he assumed receivers would be impacted in some 10 percent of the covered region. Conversely, if Ligado wanted to place the towers closer together the power would have to be reduced to get the same level of protection for GPS users. For example, he said, if the towers were spaced 200 meters apart then the initial transmitter power level of the signal would have to drop to less than a milliwatt.

“What about other classes of GPS receivers? The story is slightly better but nonetheless not very good,” Parkinson said. The only type of receiver that makes it, he said, is in cell phones, which don’t have the same accuracy requirements.

“So the conclusion is inescapable, in my opinion,” Parkinson said. “It just further strengthens our previous recommendation. Reject the 10 watt proposal. It does not meet the ExCom’s goal of protecting existing and evolving uses of space-based PNT service. It’s not even close.”

Section 7

The newest and most interesting development in the Ligado controversy is the company’s June 25 request for a decision under Section 7 of the Communications Act.

Added to the Act in 1983, Section 7 has two mandates:

1) It directs that the Commission determine whether a proposed new technology or service is in the public interest within a year after a petition or application is filed.

2) It puts the burden to demonstrate that such a proposal is not in the public interest on any person or party opposing a new technology or service.

Though that seems straightforward it is not entirely clear how the firm’s request will be handled.

The Commission has considered a handful of cases under Section 7 on an ad hoc basis, the FCC wrote in a February 2018 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. That NPRM, however, is specifically underway to set the rules for how Section 7 will be implemented. In other words the process for handling Section 7 requests is in the middle of being changed.

Among the matters that the FCC is considering is how to decide if a technology is actually new, including how to handle things like incremental improvements. Regulators are also proposing that, given the tight 1-year deadline, applications under Section 7 include a separate section demonstrating that a new technology or service is both technically feasible and available for commercial use.

The GPS Innovation Alliance (GPSIA) said in its comments on the proposed rule that an applicant should have to demonstrate that “its innovation can successfully transition from a laboratory environment to a production environment as well as a ‘real world’ environment” and that its equipment can be produced using commercially available components and representative manufacturing techniques. This can be a real issue. During the early days of the LightSquared debate there was a problem getting the new network equipment to test to see if it caused interference to GPS receivers.

The new offerings also need to be consistent with the Commission’s spectrum management responsibilities, the GPSIA wrote.

“In the case of any proposed new service or technology that will use spectrum in or adjacent to bands that support navigation services, the public interest review must take into consideration fundamental distinctions among different services—particularly navigation and communications services and their different levels of susceptibility to potential interference,” the GPSIA said. “The Commission should therefore recognize, as part of this review and its application of core spectrum management principles, the impact that a 1 dB decrease in the carrier-to-noise density ratio (“C/N0”) has on navigation services and the actions that any proponents of new transmission technologies can, and as a matter of public policy should, take to protect against these decreases.”

The Upshot

So where does that leave the Ligado proposal? Ligado is pushing for a decision under Section 7 and insists that the record is complete. The firm also insists that it has addressed issues of GPS interference (despite the points noted above) and concerns raised by Iridium and INMARSAT, two other satellites firms. Ligado also refers to the NTIA in its Section 7 application, an agency of the previously mentioned Department of Commerce, asserting that it has had its input.

“Ligado also understands that during this time the Commission has held numerous discussions with NTIA staff concerning the license modification applications and how Ligado’s spectrum plan can co-exist with users in adjacent bands,” the firm wrote in its section 7 request.

But there’s more to the NTIA element than that. As noted in the background, during the LightSquared controversy the NTIA sent a letter to the FCC laying out the government’s GPS interference test results. That letter fed into the decision to deny the LightSquared request. Under government procedure the NTIA is supposed to send another letter to the FCC, as it did before, articulating the executive branch’s position. Inside GNSS has found no hint that that has happened. Given the public opposition of the PNT Advisory Board, the opposition of a number of the ExCom agencies and the data from DOT’s ABC tests, it would seem likely that a new NTIA letter would oppose approval of Ligado’s plan.

One can’t help but wonder if NTIA is the government agency Ligado may actually be taking aim at when it refers to politics—hoping its Section 7 request will speed an FCC decision, even if it’s without a recommendation from the NTIA.

“After more than 1,200 days,” Ligado wrote, “any government agency interested in this proceeding and in 5G deployment considerations has had more than enough time and opportunity to bring forth its formal views. Waiting indefinitely for any further input from another government agency would effectively grant that agency a veto—contrary to the authority vested in the Commission by the Communications Act—and would flout the direction of Congress under Section 7 that the Commission decide these kinds of applications expeditiously.”