Karl Kovach may be the only person who can claim that he helped design every single one of the Navstar GPS navigation signals.

Recognized by GPS cognoscenti as high priest of the ICD, systems engineer Kovach serves as one of the chief keepers of the GPS Interface Control Documents, the technical specification bible for GPS signals and the essential guide for GPS receiver manufacturers. And that’s not all — the U.S. Air Force’s high-altitude, long-range unmanned air vehicle Global Hawk lands itself, thanks to an innovation Kovach patented in 2003.

Karl Kovach may be the only person who can claim that he helped design every single one of the Navstar GPS navigation signals.

Recognized by GPS cognoscenti as high priest of the ICD, systems engineer Kovach serves as one of the chief keepers of the GPS Interface Control Documents, the technical specification bible for GPS signals and the essential guide for GPS receiver manufacturers. And that’s not all — the U.S. Air Force’s high-altitude, long-range unmanned air vehicle Global Hawk lands itself, thanks to an innovation Kovach patented in 2003.

He calls himself simply “A GPS guy.”

Now at home in what he views as “the center of the GPS universe,” Kovach helps coordinate The Aerospace Corporation’s support to the GPS Wing at Los Angeles Air Force Base in El Segundo, California.

He monitors constellation performance and management, navigation signal development, spectrum management, atomic clock technology development, and other tasks related to GPS accuracy, integrity and availability.

Kovach’s work is so central to the development of GPS and to the safe, dependable operation of all military and civilian aspects of it — that it’s endearing to learn he’d had no clue what the acronym stood for when he emerged from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1978 with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering.

Lured in part by a desire to work in the space shuttle program, the self-described “former long-haired surfer” from the small citrus-growing town of Whittier, California, decided to shock his friends by joining the Air Force straight out of UCLA. But instead of going to the space shuttle, the newly minted 2nd Lt. Kovach was assigned to the Navstar GPS Joint Program Office (JPO), where he helped put together the specifications for production prototype user equipment contracts.

“There were tons of obstacles, from figuring out what a GPS receiver actually needs to do, to getting a minimum set of configurations defined to satisfy the peculiar needs of all those military user platforms: aircraft, ships, tanks, and handhelds,” he says.

But the most daunting obstacle was that so many people simply didn’t believe in GPS in the late 1970s.

Kovach remembers that the biggest opportunities came from NATO and other military customers, and from exploiting the incredible growth in digital processing circuitry. “The strategy was a lot of hard work by a lot of talented folks, and not giving up when GPS kept getting canceled,” he says.

Make Way for GPS

In 1980, the first user equipment contracts were awarded.

It was not a small accomplishment. Kovach remembers carrying an X-set in 1979, when it was the top-of-the-line GPS receiver. It weighted about 60 pounds —not including the computer, which doubled the weight— and had to be cooled with dry ice for flight tests. “Now you can get more powerful GPS capability in a watch,” he said.

Since then Kovach’s career has rocketed along almost at the same breakneck speed as the absorption of GPS technology into industry and society at large.

He capped eight years’ active duty as commander of the GPS Control Segment at California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base. In that position, he directed the Initial Control System operations, managed the deployment of the current Operational Control System (OCS), and guided the transition of the OCS to Colorado’s Schriever Air Force Base.

In 1986, Kovach moved to ARINC. Founded in 1929 as Aeronautical Radio, the private company is now owned by the major U.S. airlines and provides transportation communications and systems engineering for airports, aviation, the U.S. military, and the federal government.

There Kovach served as senior principal engineer, then technical director, and finally as a fellow in the company’s Space Systems GPS program.

In 2007, he left ARINC for Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded research and development center for the U.S. Department of Defense. Aerospace had conducted the early studies on GPS during the 1960s that laid the foundation for the current system.

In 2003, the same year as his Global Hawk UAV patent, the U.S. Institute of Navigation honored Kovach with the Weems Award, given to one person each year for extensive and continuous contributions” to the development, operation, and use of GPS. That honor crowned a string of awards beginning with a 1982 “Special People Award” from the Air Force Association up through ARINC’s first Chairman’s Award given to Kovach in 2000.

A Full Portfolio

Industry insiders agree that Kovach’s multiple achievements, including authoring or coauthoring some 80 technical papers (25 of which are classified), put him head and shoulders above the crowd.

U.S. Air Force Colonel Mark Crews, chief engineer of the GPS Wing, listed Kovach’s “monumental” contributions to GPS in an email to Inside GNSS:

• Developed the original GPS signal interface specification.

• Authored the first Precise Positioning Service Performance Standard (PPS PS).

• Led the Defense Department’s PPS receiver certification effort for safety-of-flight operations in civil-controlled airspace.

• Performed the first comprehensive integrity failure mode and effects analysis (IFMEA) for GPS.

• Conceived and developed the Notice Advisory to Navstar Users (NANU), the GPS equivalent to a NOTAM the “Notice to Airmen” that alerts flyers to hazards en route.

• Created and oversaw implementation of the SatZap procedure, the standard method used by the Operational Control Segment for rapidly taking a satellite off-line for potential integrity failures.

Crews describes Kovach as “one of the most accessible and friendly” engineers he’s ever worked with, able to motivate and inspire others with an “easy-going and collaborative style.”

Most recently, after drafting much of the language for the updated PPS Performance Standard, Crews said Kovach fielded well over a hundred reviewers’ comments “like a seasoned diplomat.”

But for Kovach, the real payoff is hearing about new ways that GPS is helping save lives, whether it’s reducing collateral damage in war zones or pinpointing the best place to dig in order to free coal miners trapped by a landslide.

On his own time, the 52-year-old single dad enjoys camping getaways with daughter Karlie, age five, on their 40 undeveloped acres in wine-growing country near Temecula, a city in California’s Inland Empire region.

“One of the dreams I’ve been keeping for when I finally grow up is to put in some grapes,” he says. “Maybe one day I’ll be standing atop the hill with my horse, watching those vines grow.” He recently played around with GPS to stake out prime spots for particular varieties including his favorite, Sangiovese, a light, peppery Tuscan red that loves hot, dry locales.

Only one thing pinches a nerve for the affable Kovach, and that’s the move away from using the name “Navstar” when referring to GPS. For many leading engineers of Kovach’s generation, keeping the Navstar name alive is a way of honoring those who came before.

“It’s like keeping true to the Gospels as you learned them when you were a kid,” he explains. “And it’s cool—we’re still guiding human kind by the stars. They’re man-made navigation stars, but they’re still up in the heavens and we still call it a constellation of satellites.”

Kovach’s coordinates:

33° 55’ 06.5” North/118° 22’ 49.9” West

COMPASS POINTS

Nickname:

K2 or “K Squared”

Engineering specialty

GPS system engineering.

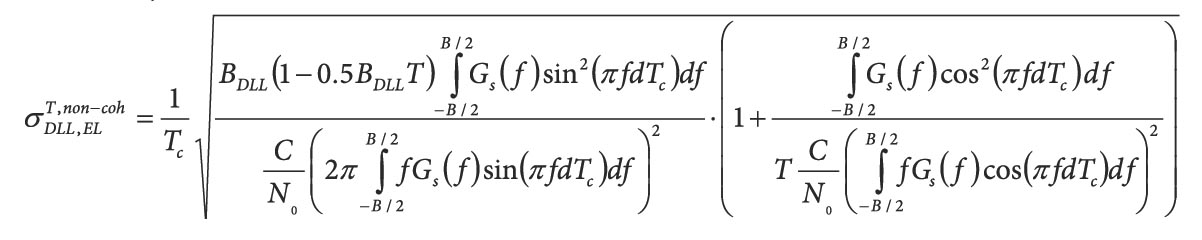

Favorite Equation

“M = T + E” where “M” is the measurement, “T” is the truth, and “E” is the error. (“One of the hardest problems engineers face is in getting the algebraic sign right – this equation is a good one for that. I like that the “M = T + E” equation works for the terms in the broadcast navigation messages from the on-orbit Navstar satellites.”) “If I could get away with it, I’d say “t = $” where “t” is time and “$” is money.”

First heard about GPS

He showed up at Los Angeles Air Force Station in 1978 and was assigned to the Navstar GPS JPO. “They told me GPS stood for something like ‘General Purpose Satellite’ (they weren’t too sure), and that I had better get myself on over there to sign in.”

GNSS Mentor

Lieutenant Colonel Mel Birnbaum, Navstar GPS chief engineer 1979 — 1981. “My first real boss and one helluva engineer."

Influences of engineering on his daily non-work life

“I guess I think like an engineer. It just seems natural to use technology to make my life easier/better. I’m not much of a ‘gadget freak’ though — except when it comes to cool toys for my daughter. “

His Compass Points

Number One. “My daughter Karlie helps me to remember the world is a wonder-full place with lots of fun to be had.”

GNSS. “Friends and colleagues remind me I’m a small cog in a big machine and that it takes a lot of cogs pushing together to make progress."

Memories of my parents.“My father passed away several years ago, and the older I get, the wiser I realize he was.”

Knew GNSS Had Arrived When . . .

. . . soldiers in the field during the first Gulf War asked their families back in the States to buy and send them civil GPS receivers to use.

Popular Notion About GNSS That Most Annoys

“My pet peeve is on dropping the proper name ‘Navstar,’ because Navstar is the name of the best global positioning system in the world.”

What’s Next?

“The whole connectivity thing (information everywhere at all times) and new human-machine interfaces to exploit it. GNSS is just the spatial and temporal underlayment for the information superhighway.”

Human Engineering is a regular feature that highlights some of the personalities behind the technologies, products, and programs of the GNSS community. We welcome readers’ recommendations for future profiles. Contact Glen Gibbons, glen@insidegnss.com.