This present edition of our “Human Engineering” article features a man who is not actually an engineer, although we believe the exception, in this case, is worth making.

“I am a licensed commercial airplane pilot with two undergraduate science degrees and two master’s degrees,” said James Joseph “JJ” Miller. “At NASA, I am a technologist manager overseeing the work of a team of engineers at several NASA field centers across the USA.”

How JJ Miller got to where he is is a remarkable story. “I started out doing hands-on technical work, operating aircraft, then spent nearly a decade in management at United Airlines, finally transitioning to serve as a policy lead in the U.S. government,” he shared.

Miller’s family record reads like an outline of the last 100 years of American history. It’s all here: World War I – Miller’s great-grandfather fought “over there”. During World War II, the aircraft carrier USS Wasp was torpedoed and sunk in the Pacific, with many young American seamen killed or injured. One of the injured was Miller’s grandfather.

Another generation later and a new form of uprising swept across the country, a social revolution in the 1960s; once again young people were at the forefront, showing us all a new way to be American. Miller’s own parents played their part in that movement.

Miller’s two uncles went to fight in Vietnam, returning to celebrate arm-in-arm with the flower children of the civil rights movement. And in an indirect way, the Vietnam War had a role in bringing Miller together with his future wife.

Miller grew up in the era of the space race, when humans first escaped the bonds of Earth and reached for the stars. He ran away from home repeatedly, hitchhiked across the country more than once, worked overseas, worked with his hands, grew up, came back home and went to work for NASA. Along the way, he even learned how to spell “GPS”.

Back to Start

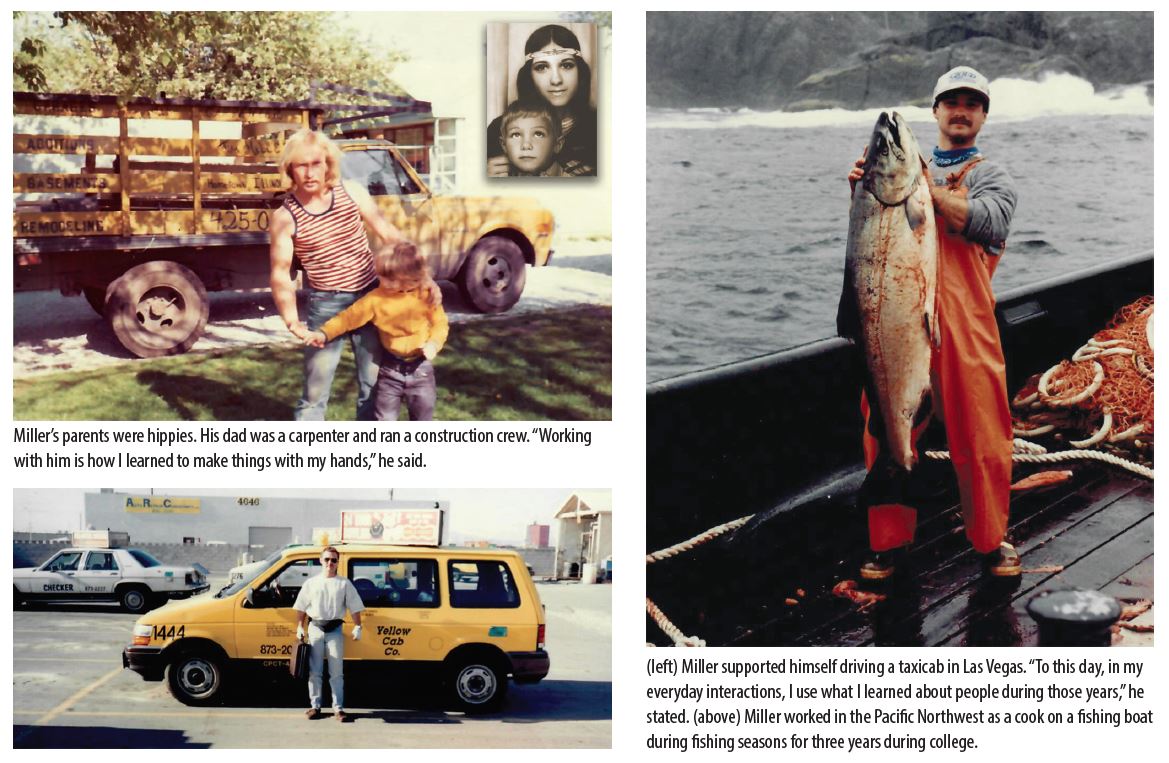

“I was born on the south side of Chicago, in Oak Lawn, Illinois,” Miller told Inside GNSS. “My parents were hippies, both just 17 when I was born. It was 1965, the civil rights era.” Among his favorite memories is that of riding on the back on his dad’s Harley Davidson motorcycle.

He learned about the value of money early on: “I earned a penny for every cigarette butt I picked up the mornings after one of my parents’ parties.” And he learned the meaning of the word “reputation”. “I went to the same elementary school that my father did. The school principal told me I better not be a trouble-maker like my father was! My dad had punched the principal in the nose on accident when he was breaking up a fight my dad was in.” For two years, Miller said, he was in so much trouble in school his desk was next to the teacher’s facing the students.

“My mom grew up in Chicago like I did,” Miller said. “Unfortunately, she left the fami ly when I was young, and so I did come from a broken home. My father raised me by himself when my mother left.” One thing his mother gave to Miller was a love of reading. “She used to designate ‘quiet times’ because of her migraine headaches. Neither of my parents finished high school thanks to me landing in the their laps, but they instilled a love of reading by bribing me to be good with comic books. They just wanted me to be quiet, but the unintended consequence was that I became a lifelong reader and learner.”

Miller added, “I would be wealthy today if I had kept my comic book collection.”

During his early years, Miller did construction with his father. “My dad was a carpenter and ran a construction crew in Chicago. Working with him is how I learned to make things with my hands. And I also learned what I would be doing for a living if I did not continue in school. Blisters and sunburns lit a fire under me on the importance of education.”

Miller’s mother would eventually return and rebuild her relationship with her son. “She drove me from Chicago to Carbondale, Illinois, in 1985, when I first entered college and flight school at Southern Illinois University (SIU). She then helped me pay for two semesters of my senior year, using money from her retirement account.”

Finding His Way

Paying for school was always an issue for Miller. “At the end of my freshman year at SIU,” he said, “I saw an article in our school newspaper about jobs in Alaska. And so I bought a bus ticket to Seattle, then walked the docks fixing fishing nets for food until I landed a job as a cook on a fishing boat named, no kidding, ‘Alaskan’. I spent the next three salmon fishing seasons all over the Inside Passage of Alaska.” The beauty of the great northern wilderness was breathtaking and, for a poor college student, the money was pretty good too.

In 1988, now a young airplane pilot and undergraduate at SIU, Miller needed to find a research topic for a study-abroad program. “My professor/advisor at the time was Dr. Terry Bowman, a former USAF Air Traffic Controller. One day he remarked that ‘GPS’ was going to be a ‘very big deal’ and that I should ‘get into it’. I responded, ‘What is GPS, and how do you spell it?’ ”

This rather enlightening conversation resulted in Miller studying “down under” at the Curtin University of Technology (CUT) in Perth, Western Australia. “And my conversations with Dr. Bowman continued for decades after,” he said.

While in Australia, Miller focused on the geopolitical implications of a foreign nation, in this case Australia, using an American military system for civil aviation applications. “This work still goes on at NASA,” Miller said, “as new nations join the GNSS community, introducing new constellations and services with a vast scope of utility and application.”

The GPS constellation being so novel when Miller was first introduced to it, there were many questions to be answered, concerning things like signal performance for safety-of-life applications, or who would be liable if services were disrupted. For a young GPS expert from the American heartland, the reception by CUT faculty was therefore understandably quite warm. “As it turned out,” said Miller, “Australia, with sparse terrestrial nav aids spread out across its vast interior, had a keen interest in this new ‘leap-frog’ technology. I had stumbled upon a red-hot research topic at an impeccable moment, having no idea that it would launch a most interesting and gratifying career.”

It was an important step in Miller’s trajectory, and another chance to have some fun. “I made some extra money in Australia rounding up sheep using a motorcycle and an overly friendly dog. We moved the flock from one paddock to another to eat and drink. It was one of the most fun and peaceful jobs I ever had, racing the sunsets.”

In 1990, back in the USA, Miller received two undergraduate degrees from SIU Carbondale: an Associate’s in Applied Science, Aviation Flight, and a Bachelor of Science in Aviation Management.

The Fun’s Just Starting

Miller was now a college graduate, but adventure was still in his blood. “While I was contemplating graduate school,” he said, “I went to work for my uncle in Las Vegas, driving a taxi-cab during the night shift; one of the uncles who served in Vietnam. My intention was to do it for a short while as I accrued flight time, but it was too much fun and I stayed a lot longer than I had intended. I ended up doing it for two straight years!”

Miller got his Nevada Taxi license in 1990, just after he turned 25, which made him the youngest taxi driver in the entire state. “To this day, in my everyday interactions, I use what I learned about people during those years,” he stated.

Once again though, the classroom beckoned. In 1995, Research for his Master’s thesis took him back to Australia, this time to the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Space Center for Satellite Navigation in Brisbane.

“By this time my professional contacts in Australia were many,” Miller said, “and I was fortunate to be sponsored by Brian O’Keefe, executive at Australia’s Civil Aviation Authority in Canberra. I was also in contact with key airline executives back in the United States. In the aviation world, as in so many other fields, once you prove yourself to a key player, additional introductions can fire your career trajectory up and away. Thus, after doing research under Professor Kurt Kubik at QUT, I was offered a paid internship with Captain Bill Cotton at United Airlines, near my home town of Chicago.”

Captain Cotton was and is still viewed as something of a pioneer in the aviation industry. He had coined the term “Free Flight” to describe what GPS/GNSS flight flexibility could mean for the future of the aviation community. United was the largest airline in the world at the time, and was investing heavily in using GPS on its new fleet of B747-400s.

These aircraft were the first to be equipped with a Honeywell avionics package known as FANS-1 (Future Air Navigation System), which enabled aircraft to downlink a GPS position fix to controllers on the ground. This became the precursor to adoption of Automatic Dependence Broadcast in the industry, and saved the airline millions of dollars per annum by enabling it to fly new direct routes over Russia without a refueling stop.

In 1996, Miller became Program Manager/Sr. Staff Specialist, Flight Standards and Technology, Flight Operations, at United Airlines World Headquarters in Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

“While at United, I became a vocal advocate and defender of GPS on numerous airline industry committees,” Miller said, “and thanks to Ann Ciganer of Trimble and the US GPS Industry Council, I was invited to the White House for the unveiling of the 1996 Presidential Decision Directive (PDD) on GPS.

“A year later, in 1997, I represented United at the World Radiocommunications Conference, when GPS faced an existential spectrum encroachment threat from the Mobile Satellite Service industry. The experience truly exposed me to the geopolitics of GPS. At United alone, our airline was investing millions of dollars in GPS for new avionics capabilities. I realized that airlines had a responsibility to team with regulators such as the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] to ensure such investments were protected.

“At the same time, the FAA and other regulators needed industry to help support them in international standards forums. These activities led to my briefing the FAA Administrator, NASA Administrator, FCC Chairman, and other key policy makers. At the International Air Transport Association (IATA), we created the Spectrum Protection Steering Group (SPSG), and I was appointed as its spokesperson for the U.S. Ambassador at the next WRC, held in Istanbul in 2000.”

After working at United for nearly a decade, Miller found himself being recruited by the First Undersecretary of Transportation, the Honorable Jeffrey Shane, Office of the Secretary at the Department of Transportation (DOT). The transition from academia, to industry, to government had progressed quite smoothly.

One of his first tasks at the DOT was to chair the interagency government group that would update the 1996 PDD, and turn it into the 2004 President’s PNT Policy, still in effect today. “We jointly developed the charters for the still-existing PNT EXCOM, National Coordination Office (NCO), and National Space-based PNT Advisory Board, where I have served as the Executive Director, working closely with the ‘Father of GPS’ Dr. Brad Parkinson, for well over a decade.”

More Than One Kind of Love

2007 was a good year for J.J. Miller. He had risen to Sr. GPS Technologist at NASA. He had already worked in many overseas locations, representing United Airlines. And, as it happened, many of his older friends were Vietnam-era veterans who had settled in Asia upon retirement. Now, something extraordinary was about to happen.

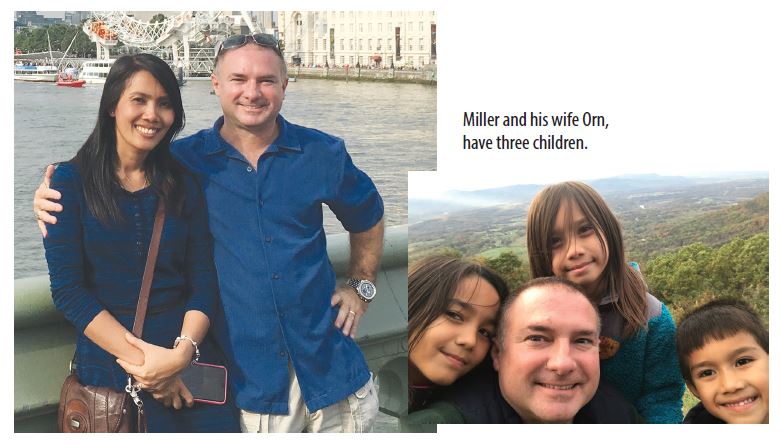

“I was on a trip visiting some friends in Southeast Asia, and, well, I met my wife, Orn. She was working as a registered nurse in Kohn Kaen, Thailand. She was the sweetest person I had ever met. Orn grew up in a small village in Thailand, near the Lao border.” To Miller, she was beautiful and exotic, and he felt like he was living a great adventure. The rest, as they say…

“Twelve-plus years and three kids later,” Miller said, “Orn and I are continuing our adventure together.” Miller has a lot to say about family life, but we’ll get to that later.

Miller’s star was still rising. In 2009 he was made Deputy Director, NASA Headquarters, Policy & Strategic Communications (PSC) Division, Space Communications and Navigation Program, Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, Washington D.C. And he received a second Master’s degree, this one in International Policy and Practice, Space Policy from George Washington University.

“I view the progression of my career as the textbook example of being in the right place at the right time,” he said. “GPS was becoming operational just as aviation authorities around the world were beginning to realize the enormous potential benefits to be gained by transitioning to satellite navigation.

“I love GNSS because of the benefits it delivers to humanity on a daily basis,” Miller added, “and these benefits appear to expand exponentially as the technology evolves and becomes more integrated into every facet of our lives.”

Talking Work

Miller’s responsibilities at NASA are to represent the Agency in all national and international GPS and GNSS policy matters, and to keep the political leadership apprised for their final reviews and approvals. This includes staffing the NASA Deputy Administrator for the PNT EXCOM, and leading the NASA Delegation to the United Nations’ International Committee on GNSS (ICG).

“Our engineering projects focus on ensuring that GPS modernization meets emerging science and space operations mission requirements,” Miller said, “as well as coordinating with other PNT service providers and GNSS constellations, to ensure their operations are fully interoperable for space users.”

Miller has been personally responsible for any number of important projects. “An early example,” he said, “was the securing of approval from the U.S. Air Force to place laser retro-reflectors on to GPS IIIF. This will enable precise optical ranging to compare with the traditional radio-metric data already being processed and will allow operators to isolate and correct systematic errors.”

Another important project involves the use of a Search and Rescue (SAR) payload on all emerging GNSS constellations. Miller sponsors the MEOSAR engineering group, headed by Dr. Lisa Mazzuca. Her team is focused on optimizing emerging GNSS SAR payloads and distress beacon capabilities, and utilizing a modernized ground segment/station that can bring spread spectrum satellite and radio signals together for the most efficient rescue operations.

“Global interoperability is a key goal of ours,” said Miller, “and we are proud to report that the NASA SAR ground station was the only U.S. facility to track the November 2018 Soyuz launch abort event in real-time. MEOSAR is what our astronauts rely on.”

Miller said his team is also quite proud of its work towards the adoption, by the United Nations’ ICG, of a multi-GNSS Space Service Volume (SSV). Miller was the lead author of the SSV article featured on the cover of the January/February 2019 issue of Inside GNSS. “The SSV began at NASA for GPS in the 1990s,” he explained, “and was predicated on the notion that GPS energy broadcast around, or spilled over the limb of the Earth could be utilized by satellites and other space users on the other side up to GEO altitudes.”

GPS was built for terrestrial, aviation, and maritime users, not space assets, and so much work had to be done to prove this concept. This was initially done by Frank Bauer of NASA, and was introduced by Miller and his engineering team at the ICG for consideration by other PNT service providers building newer GNSS constellations.

At ICG-13, in Xi’an, China, in 2018, after several years of international analyses, Miller was recognized along with Dr. Werner Enderle of the European Space Agency (ESA) for their contributions in this area, and the publication “The Interoperable Global Navigation Satellite Systems Space Service Volume” was released by the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs. <http://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2018/stspace/stspace75_0_html/st_space_75E.pdf>

“This document thus becomes a key enabler for mission planners out to GEO altitudes and beyond,” Miller said, “and it sets the stage for NASA, ESA, and other partners to equip emerging space platforms, such as the Lunar-orbiting Gateway, with GNSS. At NASA, we are specifically aiming to use GNSS for lunar space ops missions in the foreseeable future.”

Home Matters

Despite, or perhaps because of, his other-than-conventional upbringing, Miller, has gone on to become a great success. Through it all, the ties of family have remained strong.

“I have two younger brothers, one who is a PhD in Economics, the other with a Master’s degree in Social Work,” he said. “I am told that I was their role model, being the oldest and first in the family to attend university. I think the truth is more along the lines of they saw how much fun they might have at college parties.”

Miller keeps his grandfather’s Purple Heart from WW II in his home office. “He was on the USS Wasp when it was torpedoed by a Japanese warship. In going through his things, we found that he had saved newspaper clippings, including an article about both him and my great-grandfather, who fought before him in WW I.”

A century on from the Great War, Miller said, “I am proud of my family history. I like to think that those two generations contributed for our entire family, and that perhaps I am doing my small part now working for NASA.

“Both my parents are still alive, and only about 70 years old, since they were so young when they had me. My mom lives in Phoenix, Arizona, far away from Chicago winters, and my dad moved in with me just last summer in Bristow, Virginia, to help raise his grandkids.

“Orn had to retake all her medical exams to transfer her Thai license credentials to work in America. She is now a Registered Nurse at the Novant Prince William Medical Center in Manassas, Virginia, and has been there for over five years.”

JJ and Orn Miller are proud parents of three children. Natalie, 10 years old, is in fifth grade. Olivia, eight, in third, and Aiden, six, is in first. “They were all born in July and August,” Miller noted, “the fruits of staying warm in winter. Having them so close together was challenging to manage at first, but now they take swimming, gymnastics, and tae kwon do classes all together in the same age group, thus making it easier for daddy to manage taxi service.

“NASA is ranked the number one place to work in the U.S. government, largely due to its family-friendly work policies. The hardest part is how much the kids miss you when you travel. My responsibilities include overseeing much international work and collaborating with the U.S. Department of State. I try to soften the blow by bringing back goodies from around the world. My children have eaten chocolate from many nations, and have souvenirs from almost every continent. Show-and-tell at school has become an event for them.”

In his free time, Miller enjoys a variety of hobbies, pastimes and passions, from vigorous physical activities to more intellectual pursuits. “I practice Muay Thai kickboxing and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu for stress management, and my bedroom is stacked full of history books. I am a beach bum when not working, and still travel the islands whenever I can.”

If anyone is thinking Miller’s life sounds like it would make a good book, have no fear, it’s being written: “Finally, I am writing a book about a young kid from the south side of Chicago who is born broke during the Apollo years but ends up working for NASA decades later.”

Earlier we suggested that Miller’s life contained an outline of the last 100 years of American history. Actually, it is much more than that. JJ Miller’s story also points to the future. Through his work and in his family life, Miller is passing a torch to the next generation, a next generation of engineers, space scientists and administrators, and a next generation of little Millers. And, we feel, we are sure, he has many more extraordinary things to do before the job is done.

Compass Points

Professional Path

James Joseph “JJ” Miller describes himself as, “a technologist manager overseeing the work of a team of engineers at several NASA field centers across the USA, from Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) to Glenn, Johnson, Kennedy, Ames, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) on the west coast.”

He is currently Deputy Director, Policy and Strategic Communications (PSC), Space Communications and Navigation Program (SCaN), Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate (HEOMD), at NASA Headquarters.

Before working at NASA, Miller worked for United Airlines for nearly 10 years as Program Manager/Sr. Staff Specialist, Flight Standards and Technology, Flight Operations, at United Airlines World Headquarters in Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

Other Technologies

Besides GNSS, Miller deals with a variety of technical innovations, from pushing the envelope on optical communications and navigation, to building photon detectors known as X-Ray Nav that can process pulsar energy from across the galaxy.

The Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) Program that he works in acquires and operates all the NASA communications networks, also used for traditional radiometric tracking and navigation long before GNSS came on the scene.

Professional Mentor(s)

“I have been so fortunate to have a few key professionals take an interest in my work,” Miller said, “and to serve as mentors and role models throughout my career. In college, Dr. Terry Bowman introduced me to GPS, what it was, and how to spell it. My original research was supported by Dr. Brian O’Keefe of the Australian Civil Aviation Authority. I was then hired by Captain Bill Cotton of United Airlines.

After nearly a decade representing United in governmental forums, Ann Ciganer of Trimble/GPS Industry Council made some introductions, one of which was to NASA Deputy Chief of Staff at the time, Dr. Scott Pace. He recruited me into government service and is now the Executive Secretary of America’s National Space Council, reporting to Vice-President Mike Pence. Finally, I started at DOT working for Under Secretary Jeffrey Shane and Director Mike Shaw, who taught me how to survive the bureaucracy as I transitioned from industry.

“Without any of these very talented people in my life, my career could have gone down an entirely different path.”

GNSS Event that Most Signified to You that GNSS had ‘Arrived’

Miller said, “GNSS ‘arrived’ for me when it became a successful research topic in college, leading to my first ‘real’ job at United Airlines. I believe it arrived for most other people when they first saw themselves as a pale, blue dot on Google Maps on their smart phones.”

What Popular Notions About GNSS Most Annoy You?

Miller hates it when people blame GNSS for mapping software errors, or simply don’t use common sense and multiple sources, such as their own eyes, to verify what the GNSS unit is telling them while navigating. “People should not rely so much on an imperfect technology that is susceptible to interference or errors just like any other mechanical device. As pilots we are taught to cross-check and verify everything, using all of our senses. Even our own eyes can trick us if we are not careful, and so we must augment our sight with instruments. The same goes with using GNSS – use it with care and common sense.”

As a Consumer, What GNSS Product, Application, or Engineering Innovation Would You Most Like to See?

Miller would like to see a highly reliable Advanced Kid Tracker (AKT) with Bad Behavior Alerts (BBA). “I made that up, of course. I have three preteens, and they are hard to keep track of already!”

Favorite Equation

Miller said his favorite equation is:

E = mc²

“Isn’t this everyone’s favorite?!”