The GPS community is seething over a January 26 decision by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) giving a conditional go ahead to a new broadband network with the potential to overwhelm GPS receivers across the country.

The GPS community is seething over a January 26 decision by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) giving a conditional go ahead to a new broadband network with the potential to overwhelm GPS receivers across the country.

The network is being developed by LightSquared, a firm backed by hedge fund manager Phil Falcone, who made a fortune betting against subprime loans in 2007. Falcone has been accumulating stock in wireless companies for years, reportedly convinced that smart phones and other devices will fuel a drive for bandwidth. He began buying the stock of a firm called SkyTerra several years ago, taking it over completely and renaming it LightSquared in 2010.

Falcone has now committed a significant part of the assets of Harbinger Capital Partners and other of his hedge funds to wireless, even paying hundreds of millions to another wireless firm to separate its checkerboard of frequency assignments from those of LightSquared so that his firm could have contiguous bands for its services.

LightSquared plans to provide nationwide 4G (fourth-generation) LTE (long-term evolution) mobile broadband service using two freshly updated geostationary satellites and a new network of some 40,000 ground stations.

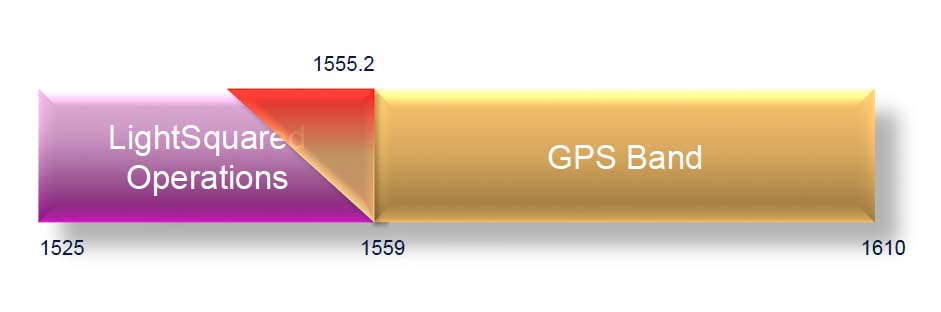

The ground stations are called ancillary terrestrial components or ATCs. As originally envisioned, ATCs were to be limited in number and intended to augment the satellite service with the on-orbit component carrying most of the load. Therefore, the level of activity in the frequency band where LightSquared wants to offer its expanded service — which ranges from 1525 to 1559 MHz — is currently relatively modest and not much of a problem for GPS users.

Most GNSS systems and related augmentation and regional services use — or plan to use — the adjacent band running from 1559 to 1610 MHz. The civil L1 GPS C/A code is a 20.46-megahertz signal centered at 1575.42 MHz. However, future civil and military signals will come even closer to the proposed LightSquared spectrum. For instance, the civil L1C signal planned for GPS Block III spacecraft (and Galileo’s equivalent Open Service signal) will be more than 24 megahertz wide.

LightSquared’s business plan now puts the emphasis on providing service via the ATCs. Each of these ground stations will put out a signal that, when measured a half mile from the ATC, will be roughly 1 billion times more powerful that a GPS signal, said GPS expert Brad Parkinson, Edward C. Wells Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Emeritus) at Stanford University.

Preliminary tests by Garmin, a GPS equipment manufacturer, indicate that the ground station signals will be so powerful that they will cause receivers as far away as 5.6 miles to fail. Receivers in airplanes 12 miles in the air could also be jammed, said General William L. Shelton, Commander, Air Force Space Command.

“If we allow that system to be fielded and it does indeed jam GPS, imagine the impact,” Shelton told the Air Force Association’s Air Warfare Symposium in Orlando, Fla., in February. “We’re talking about $110 billion industry in GPS; we’re talking about dependence on so many things in our infrastructure. This is just unbelievable.”

The more than half dozen GPS experts who spoke to Inside GNSS on the issue agreed that the LightSquared signals could potentially overload and crash GPS receivers, though the exact scope of the risk, they said, remains to be seen.

Nearly all of those who agreed to be interviewed asked not to be identified because they were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly. Several individuals declined to speak under any circumstances, perhaps because of the touchy political overtones surrounding the issue.

Murky Politics

The politics are particularly tricky because what LightSquared wants to do is a near-perfect fit with the goals of the National Broadband plan announced by the FCC last March.

Under that plan the federal government is supposed to make an additional 500 megahertz of spectrum available for broadband within 10 years. Of that, 300 megahertz is supposed to be allocated to mobile use within five years.

The FCC, which crafted the plan, is naturally enthusiastic about it. So is President Barack Obama who came out in support of broadband during his 2011 State of the Union speech and soon after announced his intention to allocate more than $18 billion to build wireless broadband capacity across the country.

But Obama also made protecting the GPS signal from interference a national priority when he announced his National Space Policy in July 2010. Moreover he reiterated his policy to work with “foreign positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services . . . to augment and strengthen the resiliency of GPS.”

That latter goal likely will be difficult if LightSquared proceeds as planned, said one expert familiar with both GPS and Galileo, the European GNSS. For those who want to use Galileo in the United States, the expert said, LightSquared is “going to be a disaster.”

That same expert confirmed what others had told Inside GNSS: it is the higher-accuracy GPS receivers — those that track up to the full 20.46 megahertz L1 C/A-code signal — that are most likely at risk from the LightSquared network as now proposed.

The GPS receivers in cell phones, another source explained, are already highly filtered. Most mobile phones have to handle signals from multiple phone networks, GPS, and other capabilities such as Bluetooth, all in a tiny handset — making heavy filtering necessary.

Cell phone makers also are not striving for the level of GPS accuracy that high-end users such as surveyors or pilots need. Cell phones generally use only a 2-megahertz band, centered at 1575 MHz, creating a buffer of more than 10 megahertz between the cell phone and the LightSquared signal,

High-end users, however, have had a quiet environment so far and have not had to incorporate such filtering. Moreover, they generally need to use a band of 20 to 30 MHz to get the accuracy they need. A 30 MHz band centered at 1575 is cheek to jowl with LightSquared’s spectrum real estate.

Several experts told Inside GNSS that the LightSquared signal posed a particular problem for aircraft using GPS for landing. Not yet clear is what the impact would be on automated dependent surveillance–broadcast (ADS-B), the Federal Aviation Administration’s billion-dollar plan to use GPS to help handle the air traffic.

Military applications could also fall into the high-end, at-risk category. The M-code, for example, uses two 10-megahertz bands, one centered at 1585 MHz and one at 1565 MHz, leaving no buffer between the lower end of the M code and the high-powered LightSquared signal.

Though some military equipment may be designed for a hostile environment, it is not clear without testing what devices could be impacted. Defense planners have another concern as well: Department of Defense (DoD) personnel often use commercial equipment.

Though some sources suggested the Pentagon lagged a bit in considering the LightSquared issue, the DoD is undoubtedly fully engaged now.

“We’re hopeful that we can find a solution, but physics being physics, we certainly don’t see what that solution would be right now,” Gen. Shelton said in his Florida speech. “LightSquared’s got to prove that they can operate with GPS over the next several months here; so, we’re hopeful that the FCC does the right thing.”

In one sense the FCC has already stepped up for GPS. They have conditioned final approval of LightSquared’s operations on the company finding a way, in cooperation with the GPS community, to address the overload problem.

Cautious Dialog

To meet the FCC’s requirement LightSquared has been working with the GPS Industry Council and others to set up a technical working group tasked with conducting tests to see what receivers will be affected by ATC signals and finding ways to “prevent harmful interference to GPS.” All the testing is to be completed and the results analyzed by June 15.

The group, set up in mid-March, is co chaired by Charles R. Trimble, Chairman of the USGIC and Jeffrey Carlisle, LightSquared’s executive vice president of regulatory affairs and public policy. They had to agree on most of the projected 14–20 members of the technical working group.

In fact, they came up with 34 members along with the two working group co-chairs and four “information facilitators.” When the reports are written, if one side or the other does not agree with a point, the opposing view will be included in brackets.

The provisions reflect the distrust the GPS community now feels toward the FCC and LightSquared. Underscoring the misgivings, some organizations, including the Department of Transportation and the Department of Defense, will be conducting their own independent tests.

The suspicion is understandable given the provisions and speed of the waiver. LightSquared submitted a request to the FCC to proceed with its ATC plans on November 18, 2010. On Friday the 19th, the day Washington normally empties out for the Thanksgiving holiday, the FCC put out its call for comments — giving just 10 days instead of the usual 30 for interested parties to respond.

Federal agencies, caught off guard, were among those scrambling to get their views in for consideration.

Though the FCC extended the comment period a bit, the final decision was issued on January 26. That decision put LightSquared in charge of setting up the working group tasked with evaluating the interference risk of its own plan.

Many in the GPS community were stunned. The November 18 waiver request was the first they had heard about the ATC network LightSquared was proposing.

LightSquared’s Carlisle told Inside GNSS that the GPS industry should not have been surprised by his firm’s plans.

“People have known that terrestrial services could be deployed in L-band as far back as 2004 when we got our license,” Carlisle said, noting that the GPS community had commented as the rules for ATCs were modified in 2009 and 2010.

“Back in the original technical characteristics in 2004 and again in 2010, it was clear that we were designing a pretty robust terrestrial network moving forward,” he added. “So, again, I know this has been thrown around out there, but I think if you look back through the actual public record and what people have said and what the FCC rules have allowed, it has clearly been possible to build one of these networks since at least 2005.”

Carlisle is largely correct. A review of the voluminous files available on the FCC’s website reveal that the firm MSV LP (Mobile Satellite Ventures) — which was acquired in a series of deals that culminated in the formation of LightSquared — did indeed get a license from the FCC to create a network of ground stations. That network, however, was limited to 1,725 stations. Moreover, the FCC’s authorization stated clearly that the premise underlying their decision was that the ATCs must be “ancillary” to the satellite system.

In a 2005 decision the FCC changed the rules for ATCs and boosted the allowable power levels. The FCC also stated at the time that it would work with other federal agencies to “assure adequate protection of the GPS.” The GPS community did provide input during some of these deliberations.

It is not clear, however, how much opportunity the GPS community had to weigh in on what came next. On November 24, 2009, the FCC granted a protective order to Harbinger and SkyTerra, shielding confidential information about Falcone’s plan to buy SkyTerra. Four months later, on March 22, the SkyTerra board voted to take Falcone’s offer.

The details of LightSquared’s business model, including the plan to create a network of 36,000 base stations were released on March 26, 2010, when the FCC issued an opinion, order, and declaratory ruling approving the deal. A letter to the FCC from Harbinger’s lawyer, filed separately and also attached to the FCC ruling, makes clear that the SkyTerra deal was predicated on approval of a modification to SkyTerra’s ATC authority.

The FCC granted a boost in the aggregate sector equivalent isotropically radiated power (EIRP) — a measure of its transmitted power — of up to 42 dBW in a separate FCC order and authorization, also issued on March 26.

By comparison, GPS satellite antennas transmit a shaped L1 C/A-code signal with an EIRP of approximately from more than 12,000 miles away. The signal strength declines during its journey until it arrives at Earth buried beneath the RF noise floor with a power density of about –132 dBW/m2 and can only be recovered in GPS receivers by de-spreading the spread spectrum signal.

Together the two March 26 decisions gave LightSquared permission to pursue a national network with tens of thousands of high-powered ground stations. Yet the FCC did not follow the usual process to check with other federal agencies that might be affected.

“We had not seen this before,” said Anthony Russo, director of the federal government’s National Coordination Office for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing. “It had not been sent through the interagency process for review.”

“I was told that it was posted and then taken down,” Russo told Inside GNSS.

Moreover, Russo said, this fall, when he began looking for the March authorization he could not find it. A query on the document has been sent to the FCC.

Fasten Your Seatbelts

Falcone and LightSquared are now well on their way to making that terrestrial network a reality. Though the March 15 working group report describes a promising start and the process to work out frequency problems is usually pretty cooperative, the GPS community is getting ready for a fight.

A new organization called Coalition to Save Our GPS launched March 10. It had 23 members by the end of the first week, including firms and associations across the manufacturing, transportation, and aviation industries. One of the Coalition’s members has already taken the controversy to Capitol Hill, testifying on March 11 on the issue before an Appropriations subcommittee.

LightSquared also appears to be gearing up for a fight. The same week that the coalition was announced, disclosure forms and news reports indicate the firm hired at least three more lobbyists, including Shawn Smeallie and David Urban of the lobbying outfit American Continental Group. Smeallie was the special assistant to the director for legislative affairs at the Office of Management and Budget and special assistant for legislative affairs to the first President Bush. David Urban was chief of staff to former Pennsylvania Sen. Arlen Specter.

Last year, as LightSquared was gearing up to launch its new network, it spent roughly $265,000 on lobbying according to Open Secrets, which tracks lobbying and lobbyists.

A quarter of a million dollars seems like a lot of money, but LightSquared and Falcone have a lot on the line — and that may explain a good deal about the rush to push the waiver and the working group forward.

The FCC has set service milestones for terrestrial service that LightSquared must meet at the risk of losing their frequency allocations. The firm must provide service to 100 million people by 2012, 145 million by 2013, and 260 million by 2015. This is a separate set of service requirements from that for the satellites alone.

But the real issue may be financial. LightSquared has a deal with Nokia Siemens Networks to build out the terrestrial network for an announced cost of $7 billion. As of the end of February 2011 the firm says it has secured some $2 billion in debt and outside equity financing, and Harbinger has reportedly invested some $2.9 billion.

For someone operating at Falcone’s rarefied financial level, raising the rest of the billions is not necessarily difficult. SK Telecom Corp. Ltd., a South Korean wireless provider that reportedly has a hankering to enter the U.S. market, said in September it was in negations with LightSquared to invest $100 million.

But money could become an issue if the GPS testing process bogs down. Investors have many financial options, and some of Harbinger’s investors have already pulled back.

Just about a week before LightSquared filed its waiver request with the FCC, the Blackstone Group investment fund, the asset management group of Goldman Sachs Group, and the New York State Common Retirement Fund filed to reduce their investments in Harbinger.

At least part of the reason for the redemption requests, according to news reports, was that the investors were concerned about Falcone’s substantial move into the wireless market. They were not necessarily adverse to wireless, the reports indicated, but the shift changed the liquidity of the funds — an important factor in portfolio management.

Harbinger has since restructured its financing vehicles for LightSquared to enable easier direct investment in the project, according to Reuters. LightSquared is also moving quickly to cement its position and get its network in place quickly.

The company announced a preliminary agreement with Open Range Communications to formulate a multi-year strategic network partnership. If the deal is finalized, Open Range is expected to lease LightSquared spectrum.

In February LightSquared announced contracts with five potential customers, including a national retailer.

The customers were not named pending finalization of the deals. Bloomberg also reported that LightSquared was in talks with Sprint with the goal of using some of Sprint’s network to roll out its own system.

There is no question. LightSquared is a firm in a hurry.

Next Steps

Fortunately, the working group appears well underway, and LightSquared is in discussions to provide some of its new filters for the tests. The filters, developed at a cost of some $9 million according to Carlisle, are important to isolating and studying the overload effect, explained LightSquared spokeswoman Audrey Schaefer. Garmin did not have one of the filters when it conducted its tests.

Though the GPS community is dubious, Carlisle does not see the overload issue as a showstopper.

“It depends on where the science takes us and what the data points to as being the scope of the devices that are susceptible,” he told Inside GNSS. “It could be that there are devices that are susceptible that will never be used within range of an ATC base station – so you don’t really need to worry about them. Or it could be that there are devices that are susceptible that are going to be traded out for more resilient devices in the normal course of business before we are broadly deployed.”

Because overload occurs when receivers “hear” signals outside of their assigned frequencies, one of the options is to design new GPS receivers to avoid the problem. Carlisle suggested as much, and the FCC appears sympathetic to this view, pointing out in its January 26 decision that the “interference concerns stem from LightSquared’s transmissions in its authorized spectrum.”

There are, however, hundreds of millions of GPS receivers already in place. Some are essential to safety of life services, some pace the transmission of power and information on the Web, some guide planes, buses, and cars. The importance of these receivers to services and to the economy is incalculable.

The cost to upgrade even a fraction of the receivers in place would be astronomical. More importantly, the time involved is likely to be far longer than LightSquared — which the FCC says can’t proceed until the “interference issues are resolved” — can likely afford to wait.

Other options may exist, according to the experts consulted by Inside GNSS. LightSquared could build more, lower-powered ground stations than are now planned. They could also focus their service, for now, on the lower end of their authorized frequency bands, effectively creating a buffer.

LightSquared may find itself urged to think about these and other options by the FCC — which is in something of a bind. The commission has allowed LightSquared to proceed and granted a waiver for the ATC network. If LightSquared fails now, it will likely put a dent in the National Broadband Plan. Moreover other firms, looking hard at the broadband market and LightSquared’s experiences, could find themselves thinking twice about providing satellite-based wireless service.

How the FCC handles the issue over the next six months is critical to whether the issue devolves into a political fight involving Congress or the necessary negotiations that could lead to a solution. A little extra time to work things out and a solid show of support for both communities could be the keys to finding an approach both sides can live with.