After a four-year delay the Federal Communications Commission is set to vote on whether signals from Europe’s Galileo satellite navigation system can officially be used in the United States.

Dubbing November “Space Month” FCC Chairman Ajit Pai said in a blog post the commissioners would take up nine space-related items in its November agenda — including a vote on whether to authorize use of Galileo signals. The next open commission meeting is Nov. 15.

“We start with improving a satellite-enabled technology that millions of Americans rely on every day without even knowing it: the positioning, navigation, and timing service known to most Americans as the Global Positioning System, or GPS,” wrote Pai. “Consumers regularly use GPS to navigate while driving, to locate a store, and even to find our phones. Meanwhile, businesses are using GPS for high-precision agriculture, fleet tracking, and monitoring drones. Given all these uses, it’s important for us to take steps to improve GPS when we can. That’s why the Commission will vote in November on allowing American devices to access the European global navigation satellite system, known as Galileo. Enabling the Galileo system to work in concert with the U.S. GPS constellation should make GPS more precise, reliable, and resilient — a boon to consumers and businesses alike.”

Though the blog post only announced an agenda item on Galileo, the post strongly suggests Galileo will get an official thumbs up.

Tim Farrar, a technology consultant specializing in the satellite industry and the founder of TMF Associates, agreed that use of the Galileo signals is headed for approval.

“You don’t normally bring these things up for a vote unless you know the answer,” said Farrar. “You’ve got three Republicans and one Democrat and it will be very strange for the FCC chairman to bring something up onto the agenda if he didn’t have the support of his Republican colleagues.”

Life Or Death

That approval is more than symbolic. Though the signals have been broadcast into the U.S. for some time and are used unofficially without penalty, they could not be used for official, non-federal purposes.

In January 2015, for example, the FCC decided wireless phone companies could not use non-U.S. radionavigation-satellite services (RNSS) like Galileo or Russia’s GLONASS to meet tighter Enhanced 911 (E911) location standards. The greater accuracy would have improved the ability to locate a cellphone caller, especially if they are calling from indoors where GPS signals do not penetrate as easily. The more satellite signals that a receiver can use the more accurately first responders can find a heart attack victim in a large apartment building or in an urban area where signals get blocked and bounced around by buildings and reflective surfaces or in a heavily wooded area where foliage makes GPS reception more difficult.

“With mobile callers now accounting for more than 75 percent of 9-1-1 calls in many jurisdictions, ensuring the availability of RNSS-derived position fixes is vital to the continued success of wireless Enhanced 9-1-1, and the future Next Generation 9-1-1 ecosystem. Granting the EC’s waiver request will provide a new tool that handset manufacturers can use to help reliably locate their customers,” wrote the NENA 9-1-1 Association in February 2017 comments to the FCC.

“Beyond improving the availability and reliability of RNSS fixes for 9-1-1 callers,” NENA wrote, “approving the EC’s (European Commission’s) request will make available dramatically superior positioning signals on an accelerated timeframe. Much like the U.S.-based GPS “Block-III” upgrade, the Galileo system will support new positioning signals, including a double-power signal with improved multipath mitigation characteristics on the 1191.795MHz “L5/E5” frequency. Whether from the NavStar/GPS constellation or the Galileo constellation, this new signal class will provide significant public safety benefits: It will improve the availability, speed, and quality of indoor fixes by better-penetrating building materials, better resisting multipath errors, and better covering available signal apertures. Moreover, its use in combination with existing and future RNSS L1/E1 signals at 1575.42MHz will permit receivers to directly cancel the single largest source of positioning error, localized ionospheric propagation delay.”

Ligado

After fits and starts the waiver request was submitted to the FCC sometime in late 2014 and sat until January 2017 when the FCC asked for public comment on granting the waiver.

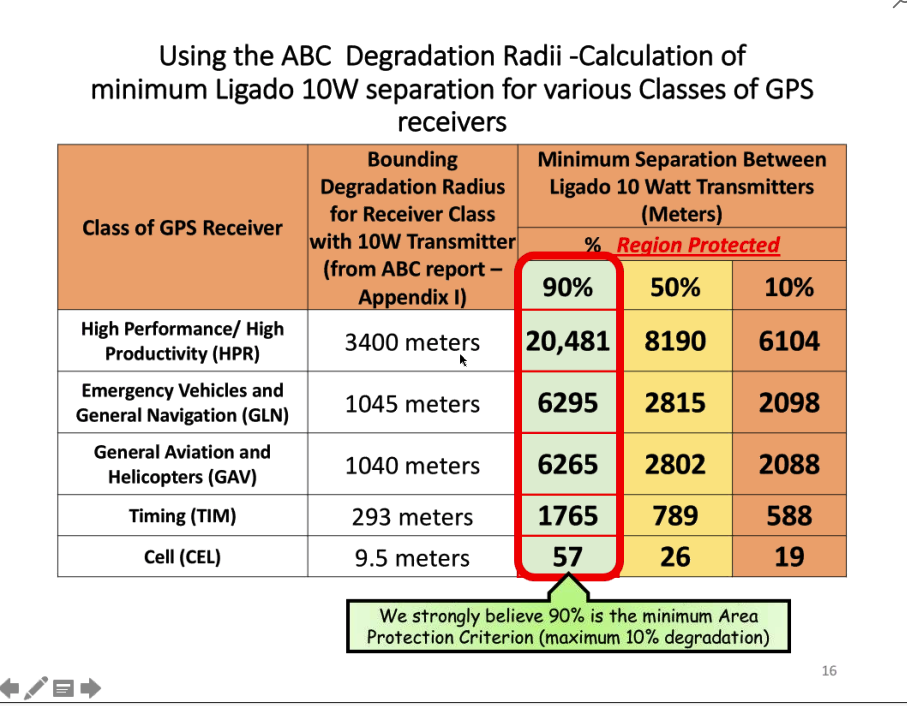

One of the factors for the delay in authorizing Galileo appears to have been centered on a proposal by Ligado Networks (formerly LightSquared). The Virginia-based firm wanted to use its frequencies, which were originally licensed for satellite-only applications in a band neighboring the RNSS spectrum, to also support terrestrial communications. Tests showed that the proposed shift posed an interference risk for GPS receivers, a risk that would apply to other satellite navigation constellations.

The approval of Galileo would have made sorting things out all the more complicated for both Ligado and the FCC — which was under pressure to find more bandwidth for mobile applications. The FCC also initially appeared to view the GPS interference issue more like an interference issue between two communications services than an interference problem between two applications that use signals in markedly different ways. Subsequent tests appear to have clarified the interference risk.

Farrar sees the pending vote as a “smack down” for Ligado and an indicator that the FCC is in no hurry to address their request.

“There are so many items on the agenda related to space,” said Farrar. “I mean Pai’s blog post described it as space month — but there isn’t anything about Ligado. And as I say there’s something (on the agenda) about Galileo, which is the opposite of what Ligado wanted. And I take that as a sign that there’s nothing positive likely to happen on the Ligado front any time soon.”