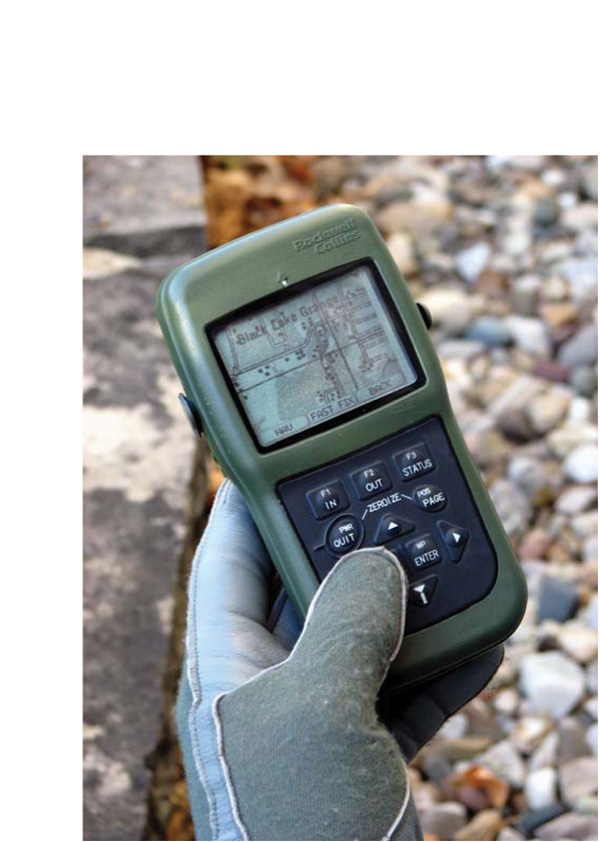

U.S. Army DAGR GPS receiver

U.S. Army DAGR GPS receiverThe Army is working on GPS equipment that would connect with a single, user-friendly device like a smart phone or through a single hub to reduce the number of devices a soldier has to carry and to facilitate software updates.

The work is part of a wide-ranging effort at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to shift the focus away from having positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) capability in each device —such as a DAGR (Defense Advanced GPS Receiver) or range finder — connecting equipment into a single device that supplies the necessary PNT information.

The Army is working on GPS equipment that would connect with a single, user-friendly device like a smart phone or through a single hub to reduce the number of devices a soldier has to carry and to facilitate software updates.

The work is part of a wide-ranging effort at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to shift the focus away from having positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) capability in each device —such as a DAGR (Defense Advanced GPS Receiver) or range finder — connecting equipment into a single device that supplies the necessary PNT information.

“Right now a solider may have a DAGR, which is the current military SAASM [Selective Availability/AntiSpoofing Module] GPS receiver we put in the hand of a soldier,” said Kevin Coggins, the product director for PNT in the Program Executive Office for Intelligence, Electronic Warfare, and Sensors. “He uses that for call-for-fire. He uses it for navigation. He can even use it to get time out of. He might also have a laser range finder — which has a GB-GRAM (Ground-Based–GPS Receiver Application Module) embedded in it.”

“Already now he’s got two things,” Coggins continued. “If he’s got a Rifleman Radio, it has a GPS receiver in it. I can keep adding equipment that the solder might carry that would have its own GPS. Every time he’s got a GPS he’s got another device that’s draining batteries, that has to have it’s own antenna, that he has to load encryption keys into.”

Instead, if military personnel carry a device from which they can get “really good PNT information,” Coggins told Inside GNSS, “be it from a GPS and other things in addition — and it can transmit that data . . . in a secure way to the other equipment — you’ve got only one device draining batteries for the purpose of PNT. You’ve got one thing that you have to load the keys into. You’ve got less stuff that the soldier has to worry about and carry.”

Then, all the devices are linked through a smart phone, the interface soldiers use more than any other, “they can pick up the military device and ‘it just works,’" said Coggins

“So, the smart phone is one of those things we can feed PNT information to — so, the soldier can use the displays on there and the processing power on there,” Coggins continued. “Not only can the GPS data go to it, but the Nett Warrior System and the Rifleman Radio system link to it also, so that your communications link can pull data down and show you where your buddies are. And you’ve got the solider holding one display. The way it is today, he’s got one display for every system (device) he’s got.”

The devices and phone are connected wirelessly,” Coggins said. “We’re also taking cables off the soldier. Right now most [military] users walking around with a smart phone do have cables running up their arm.”

Yotta Navigation, a Santa Clara, California–based company, is developing the PNT Puck, which connects to a commercial smartphone via USB or secure wireless interface and will enable PNT distribution to the devices a soldier carries, Coggins said in an email. The Puck includes a SAASM GPS receiver, chip-scale atomic clock (CSAC), and inertial measurement unit (IMU), and is upgradable to M-Code.

The CSAC and IMU provide a more robust positioning solution and increase the system’s access and integrity to help address jamming and spoofing and the problems that arise when GPS signals are blocked by buildings or rough terrain.

The Puck, connected to a smartphone, has already been demonstrated, Coggins told Inside GNSS. “We’re probably a couple of years out from getting it onto a soldier.”

Another product being tested at Aberdeen is the DAGR Distributed Device (D3) developed by GPS Source, based in Pueblo West, Colorado. Coggins said D3 uses the same interface as the DAGR, enabling the military to pull multiple DAGRs off of platforms and “seamlessly” replace them with the D3.

“This is the first device capable of providing platform distribution on mounted platforms with true port independence,” said Coggins, “meaning that each system that is plugged into the D3 has full control over the port from the D3, as if the device had its own DAGR.”

System of Systems Architecture

The PNT Puck and the D3 are part of the Army’s PNT System of Systems Architecture (SoSA), which stresses “affordability, protection, scalability, efficiencies, and innovation,” said Coggins. For example, once fully in place, warfighters will be able to improve performance or improve system protection by just plugging in additional modules rather than replacing entire pieces of PNT user equipment.

A vendor with an innovative solution can connect its solution into the PNT Hub (for mounted platforms), enabling user equipment to be scaled up or down, as needed. Each soldier, vehicle, or other “platform” would have one reliable source of PNT information — eliminating the need to develop, buy, and maintain the GPS elements of a multitude of different devices. Standardized interfaces will enable the Army to upgrade PNT capabilities without changing out PNT, using devices in the same way that people can update a computer without updating their phone.

“The Army PNT SoSA will be published and go into effect in Fiscal Year 2015,” Coggins said.

Encryption can protect the devices even though they are using open-architecture interfaces, said Coggins. “As soon as you encrypt it is in a very protected interface.”

Having atomic clocks and inertial measurement units as part of the new devices protects against the loss of the GPS signal, a key element in the Army’s new Assured PNT Program, “a level-based guarantee of access and integrity of PNT information for the warfighter.”

“Assured PNT requires a shift from sole dependence on GPS to GPS plus other sources of PNT information, such as CSACs and IMUs, but also many other sources of PNT enablers,” explained Coggins.

“The level-based guarantee of access and integrity is referred to as the PNT Assurance Levels, which span from zero (0) to three (3), with zero being the least guarantee of access (equivalent to commercial GPS) and four being the best guarantee of access,” he explained. “So, we refer to most commercial devices as providing a PNT Assurance Level of zero. We refer to a military capability as having higher PNT Assurance Levels. For example, the military capability will have things such as SAASM- or M-Code–capable GPS, open-architecture scalability to include other sources of PNT, and platform distribution of PNT information.”

The purpose of the program, he said, is to tackle the access and integrity issue “because we want to assure that the warfighter, no matter what the threat or the physical environment — indoors or urban canyon like downtown in a city — to make sure that they always have access to the level of PNT access that they need and that they can always trust it.”

Scalable architecture is part of Assured PNT. Upcoming competitive opportunities will arise within the new Assured PNT program, said Coggins. Although he could not provide any details, “they are soon to be released,” he added.

The opportunity could be substantial.

The Army is the largest user of GPS or PNT equipment in the Department of Defense. “We use an order of magnitude more GPS capability than the other services. Based on that you can see the volume of need is large,” Coggins said. “With platform distribution we won’t have to buy as much as we have in the past but we will still be by far the largest consumer of military GPS technology.

“If you just look at DAGRs we have over 300,000 DAGRs,” he said. “That doesn’t include all the imbedded GB-GRAMs and all the other GPSs that we have — which is also high volume. So, there is a lot of GPS-PNT equipment in the Army.”