Probably no one else could have accomplished Brad Parkinson’s bravura performance at the joint meeting of the Stanford PNT Symposium/Marconi Society earlier this month: in the morning sketch a “short history” of radio waves from Marconi to GPS and in the evening recount a brief retrospective on the Global Positioning System from its prehistory in the 1960s to its future in the 21st century.

And in between moderate a panel of past Marconi Fellows, among whom Parkinson is the latest addition.

Probably no one else could have accomplished Brad Parkinson’s bravura performance at the joint meeting of the Stanford PNT Symposium/Marconi Society earlier this month: in the morning sketch a “short history” of radio waves from Marconi to GPS and in the evening recount a brief retrospective on the Global Positioning System from its prehistory in the 1960s to its future in the 21st century.

And in between moderate a panel of past Marconi Fellows, among whom Parkinson is the latest addition.

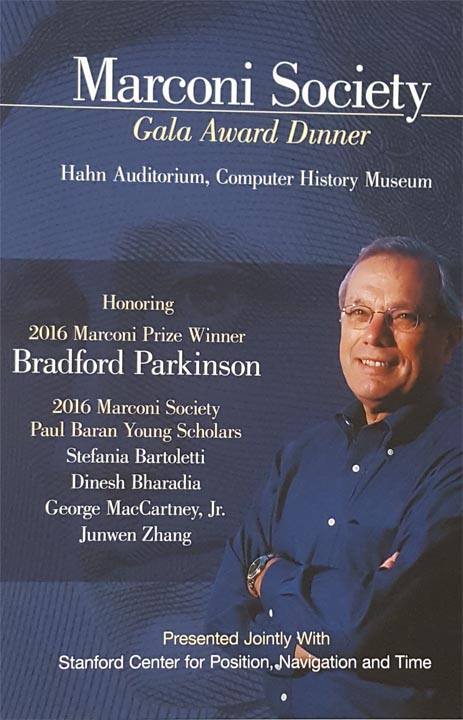

The $100,000 Marconi prize, given annually, recognizes significant contributions to the advancement of communications for the benefit of mankind through scientific or technological discoveries. In a November 2 awards dinner at the Computer Museum in Mountain View, California, USAF Gen. (Ret.) William Shelton, former head of Air Force Space Command, presented the award to Parkinson.

The first director of the U.S. Air Force’s GPS program and an emeritus professor at Stanford University, Parkinson described his effort to demonstrate “the continuity between Marconi and what he did, with all of the navigation systems since” in 45 minutes since as “trying to eat a dinosaur with a very small fork.”

Parkinson actually began his exposition on radio waves by describing the work of such scientific luminaries as Maxwell, Henry, Kelvin, and Hertz — predecessors of Guglielmo Marconi, who shared the Nobel Prize for physics in 1909 with Karl Ferdinand Braun for contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy. “These are the giants on whose shoulders we stand,” he said.

Marconi is known for making the first long-distance radio transmission, but he was also, in Parkinson’s words, “an early conceptualizer of radionavigation.” In 1934 Marconi demonstrated the use of his “microwave beam” for steering a boat from a sealed bridge using a two-band radio receiver and radio transmissions that indicated if the vessel was deviating left or right from its course.

From Marconi, Parkinson jumped ahead to Gen. James Doolittle and the network of radio ranging and marker beacons, which could be converted into “fly from” or “fly to” guidance using either audio or visual cues. This was the main new radionavigation system used in the United States until adoption of VHF omnidirectional radio (VOR) still in use today for civil aviation.

Parkinson touched on the hyperbolic systems — Loran, Decca, and Gee — and the instrument landing system (ILS), still the dominant instrument landing system for aviators. He prefaced the first satellite navigation system (TRANSIT) by recounting the inspiration of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab researchers to use the Doppler shift of transponder signals from Russia’s Sputnik to track the pioneering satellite and, later, to reverse the technique in order to geolocate receivers on the ground.

Finally, in a foreshadowing of his acceptance speech that evening, Parkinson described the arrival of GPS and its ultimate acceptance by a skeptical military establishment as a result of its demonstrated benefits in the first Gulf War against Iraq.

Civil skeptics abounded, too, in the early years of the GPS program, Parkinson pointed out, quoting a former director of the Federal Aviation Administration who declared in a public meeting, “I don’t want it [GPS]. I don’t need it. If it’s ever there, I won’t use it.”

Vint Cerf, Internet pioneer and recipient of the 1998 Marconi Prize who followed Parkinson to the podium, observed, “Even if he hadn’t invented GPS, Brad deserved a prize for that lecture,” which Cerf characterized as a tour de force.

A Panel of Marconi Prizewinners

Cerf was one of five speakers on a panel comprised of technology heavyweights, which also included Irwin Jacobs, founder of Qualcomm; John Cioffi, the “father of DSL (digital subscriber line)” and the 2006 Marconi Fellow; Martin Cooper, inventor of the first handheld cellular mobile phone and the 2013 Marconi prize-winner; and David Payne, a pioneer in the field of photonics. At the end of their presentations, Parkinson observed that it was the “most distinguished panel I’ve ever been associated with.”

Jacobs described the origins of Qualcomm in the late 1980s as a provider of satellite-based communications and tracking for trucking fleets before evolving into a mobile phone chipset supplier. He traced the adoption of GPS in cell phones to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enhanced 911 (e911) mandate for locating emergency callers. Having acquired assisted-GPS (A-GPS) innovator SnapTrack in the interim, Jacobs described a 1998 competition in which GPS demonstrated its strengths against forward link trilateration and cell ID, two techniques that had originally been expected to provide the e911 capability.

In remarks titled “The Myth of Spectrum Scarcity,” Cooper argued that it was the lack of optimal spectrum management that was the real problem.

“We have doubled the available spectrum every 30 months for the last 120 year since Marconi,” he said, referring to the increased efficiency in use of radio frequencies. “We can do that for the next 60 years.”

Criticizing the desire of license-holders to have exclusive use of their bands, Cooper said, “If you want to use spectrum efficiently, only use it at the time they need, for the bandwidth they need, only the power they need for the geographic area they need to cover.”

Cioffi some new roles or radio in the Internet, and Payne wrapped up the panel session with remarks on “Light: the Cause of and Solution for Data Overload.” Several invited speakers rounded out the PNT symposium portion of the proceedings, an international forum that has been organized by the Stanford Center for Position, Navigation, and Time and its executive director, Tom Langenstein. Video recordings of the proceedings and the speakers’ slides are available online here.

The Acceptance Speech

That evening at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Parkinson took up the GPS storyline once again — well-known in GNSS circles, but a rich enough narrative to support frequent retelling.

At the gala Marconi dinner, he prefaced his remarks with a excerpt from Niccolo Machievelli’s treatise, The Prince: “[T]here is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. . . .”

Parkinson experienced that phenomenon first-hand, beginning with his appointment in 1972 to head a “floundering” classified Air Force program — based on a 1966 report by two Aerospace engineers and known as 621B — that was advancing an improved space-based navigation system. The project had come up with 12 major alternative designs, among which was a proposal to use a four simultaneous ranging measurements to find four-dimensional (including time) position. Dozens of studies over the following years had refined the proposal but still not gotten final approval in the competitive Pentagon environment.

At his first effort in August 1973 to sell the proposal to the interservice Defense Systems Acquisition Review Council (DSARC), Parkinson received a “thumbs down” from the high-level group. Malcolm Currie, Undersecretary of Research and Engineering for the Defense Department who chaired the council, advised Parkinson to come back with a “joint” concept that incorporated the best technical features and would meet the operational needs of all military branches.

Besides simultaneous ranging, Parkinson’s follow-up proposal — hashed out the system architecture during a Pentagon “lonely halls” effort over the Labor Day weekend — incorporated space-hardened atomic clocks for the satellites and a low-power spread spectrum CDMA broadcast signal. Approval for the new plan at a DSARC meeting in December 1973 sent the program on its way toward the first satellite launch five years later.

Parkinson credited Currie, to whom he refers as the “GPS Godfather,” as one of three essential links that supported the GPS revolution. Lt. Gen. Kenneth Schultz, commander of the Space and Missile Systems Organization who had assigned him to 621B, was the Air Force’s GPS sponsor and Ivan Getting, head of The Aerospace Corporation, was the “GPS Soothsayer” in Parkinson pantheon of program heroes, joined by a long list of technical experts.

“Now GPS is known by just about everybody in the world,” Parkinson said, quoting Trimble CEO Steve Berglund as calling it “the pre-eminent U.S. brand out there.”

As Gen. Shelton said in remarks before presenting the Marconi Award, “Today we can’t even imagine a world without GPS. There’s a generation of people who don’t even know a world without GPS.”