The U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) is finalizing its blueprint for long-awaited tests to determine the power limits needed to protect GPS receivers.

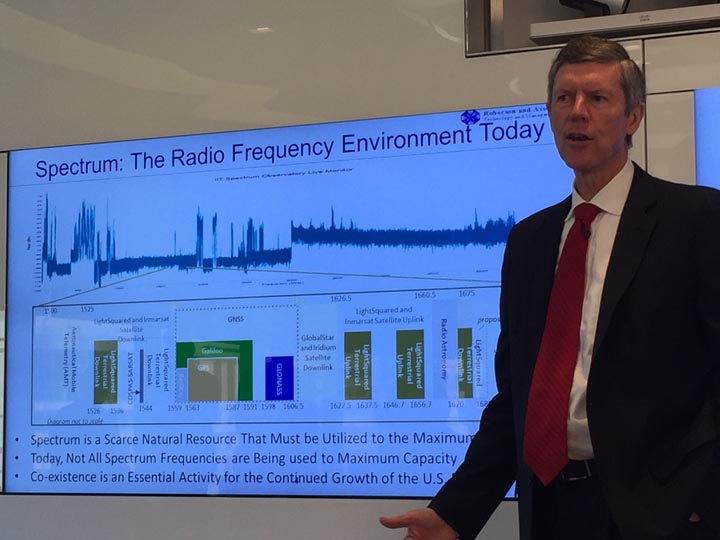

The Adjacent-Band Compatibility Assessment (or ABC Assessment) is part of a plan to develop masks — a set of power limits by frequency — for the bands near the GPS L1 signal. Eventually covering all GPS civil receivers present and future, the masks are a way to give potential users of frequencies neighboring the GPS frequencies clear limits against which to measure their plans and proposals.

The U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) is finalizing its blueprint for long-awaited tests to determine the power limits needed to protect GPS receivers.

The Adjacent-Band Compatibility Assessment (or ABC Assessment) is part of a plan to develop masks — a set of power limits by frequency — for the bands near the GPS L1 signal. Eventually covering all GPS civil receivers present and future, the masks are a way to give potential users of frequencies neighboring the GPS frequencies clear limits against which to measure their plans and proposals.

The concept arose after the Federal Communications Commission decided to freeze a wireless broadband network proposed by Virginia-based LightSquared. The company had spent considerable money and effort pursuing its national network only to have this plan set aside when tests showed debilitating interference with a wide range of GPS receivers.

Several years in the making, thanks in part to federal budgetary woes, DoT’s draft test plan was published for comment in the Federal Register on September 9, with the comment period later extended to October 16.

Details Still TBD

DoT held a public workshop October 2 to go over the test plan and solicit additional feedback. The agency, though, had yet to finalize the list of receivers it was going to test and had not yet chosen a site for the tests or finalized other details.

The plan is to have nondisclosure agreements in place with receiver manufacturers by December 1 and a final list of the GPS receivers to be tested by mid-January 2016. A presentation on the test procedure is planned either later this year or early next year with the actual testing to take place in March.

Finalizing the test requires going through and addressing the submitted comments. Although the comment period had not quite ended, and late submissions may not yet have been posted, as of press time only two comments on the test plan had appeared on the website.

In its letter General Motors suggested, among other things, that DoT should add a 4G LTE simulator to the lab tests. The company also pointed out potential receiver-on-receiver interference problems if 100 GPS/GNSS receiver antennas were tested simultaneously as currently proposed.

GPS interference expert and consultant Logan Scott said that the interference tolerance masks developed using the draft test plan “may prove dangerously permissive.”

“The GPS L1 C/A code signal used as the primary, and often sole, navigation and timing signal in most civil applications has numerous well-known structural vulnerabilities that will not be stimulated under this test plan,” Scott wrote. “Specifically, C/A codes are short and repeat themselves every 1 msec leading to a line spectrum vulnerability. Low level interference can cause sustained biases in measured pseudorange and carrier phase, often with no measurable change in observed C/N0.”

He also noted that using white noise as a stand-in for LTE signals was a particularly benign approach.

“White noise has no periodicities, and it is not capable of inducing measurement bias effects,” he said. As a result the choice could leave unaffected the signal-to-noise ratio, the criteria the DoT is using to indicate interference, and therefore not reflect the position and time errors that might be seen in the real world if the tests used a waveform.

User Experience

Scott’s point that the signal-to-noise ratio (or C/N0) may not fully reflect the potential for interference is particularly interesting given that LightSquared has launched tests focusing on actual, experienced interference. The firm insists that whether or not GPS receivers experience harmful or even noticeable changes in the presence of the LightSquared signal — that is, if there is a change in a key performance indicator (KPI) like timing or position accuracy — is the correct way to assess the compatibility of its proposed service.

“We’re not going to see customers calling in saying ‘Gee, my C/N0 dropped by -1 dB.’ They’re going to only be concerned when the functionality is there,” said Dennis Roberson, the president and CEO of communications experts Roberson and Associates.

LightSquared, which arguably has the most at stake in the outcome of DoT’s testing, has hired Roberson and Associates to test nearly 40 different GPS receivers. The testing is already underway and Roberson told reporters today (October 16, 2015) that his company would be finished with its analysis by the end of the year.

LightSquared told Inside GNSS in a statement that it would be testing for changes in the experience of current users and would not be basing their tests on the still official but wildly out-of-date 2008 GPS Standard Positioning Service (SPS) Performance Standard issued by the GPS Directorate. Citing the old standard in its draft test plan suggested that LightSquared could assert that it had met legal criteria even though that is not the way GPS is currently used.

“The overall Test Plan is not based on the 2008 Standard. The 2008 Standard was only used as an authoritative reference for the type of GPS impairments that are planned to be applied during the conduct of the device measurements,” said company spokeswoman Ashley Durmer. “The Standard is appropriate for such a reference.”

Durmer added the impairments would be “adjusted downward to reflect a typical operating environment — one with less error inserted into the GPS signal than is specified under the GPS Directorate’s minimum standard. This reduced error level increases the potential for adjacent-band LTE signals to cause an increase in position or timing errors than the GPS Directorate’ minimum standard would.”

“We’re using a device by device, class of device by class of device kind of measurement as to whether we are harming the device at a specific level of LTE injection,” said Roberson.

His firm will measure all of the devices absent the LTE signal, he said, and then with the LTE signal added at various power levels. A control receiver would be measured each time to help ensure the validity of the tests.

“The goal is to look at the user experience as it exists today,” said Roberson.

“We’re doing this looking at each of the devices with the functionality that those devices are intended to provide,” he said, “and then, are we getting out of bounds where that device is no longer providing the functionality that it’s intended to provide.”

GPS industry advocates continue to support the DoT process and disagree with the LightSquared test initiative.

“As we have said from the outset, the GPS Innovation Alliance (GPSIA) supports the multi-stakeholder process currently underway at the U.S. Department of Transportation rather than engaging in a debate with LightSquared consultants," said Heather Hennessey, executive director, legislative, for the GPS Innovation Alliance. “That said, GPSIA believes that anyone testing the compatibility of terrestrial broadband and GPS should use the one-decibel standard as an interference protection criterion. It has a long and well-established history in international and domestic regulatory proceedings as the appropriate interference protection standard, and it is not fraught with the difficulty of other standards that are impractical due to the vast number of applications of GPS and the exceedingly complex ways that interference impacts the accuracy, integrity, availability, and continuity requirements of a particular application.”