LightSquared has opened a new rhetorical front in its battle with the GPS community over the company’s efforts to convert L-band frequencies into terrestrial wireless broadband services: claiming in an August 11 letter to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that receiver manufacturers “chose to ignore” Department of Defense (DoD) standards.

In response, the Coalition to Save Our GPS, a group of GPS receiver manufacturers opposed to LightSquared’s plans, called the company’s filing an act of "desperation."

LightSquared has opened a new rhetorical front in its battle with the GPS community over the company’s efforts to convert L-band frequencies into terrestrial wireless broadband services: claiming in an August 11 letter to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that receiver manufacturers “chose to ignore” Department of Defense (DoD) standards.

In response, the Coalition to Save Our GPS, a group of GPS receiver manufacturers opposed to LightSquared’s plans, called the company’s filing an act of "desperation."

In the letter, Jeffrey Carlisle, LightSquared’s executive vice-president for regulatory affairs and public policy, argued that a passage in the GPS Standard Positioning Service Performance Standard (SPS PS) regarding a “sharp-cutoff filter bandwidth” represents a design “requirement” for GPS receivers.

Carlisle’s letter notes that the SPS PS defines the “levels of Signal In Space (SIS) performance to be provided” by the operators of the GPS system on which manufacturers should base their receiver designs — the generally accepted understanding of the status of the SPS PS and the associated interface specifications. But it then proceeds to try to turn that into a design mandate for receiver manufacturers.

“While DoD, like the FCC, does not mandate receiver performance, DoD made clear that the receiver standards set forth in the SPS comprise ‘Minimum Usage Assumptions’ that ‘are necessary attributes to achieve the SPS performance described’ therein,” Carlisle said. “Following those standards was made the responsibility of the GPS industry, the evident underlying presumption being that, having been advised what receiver criteria were necessary for them to achieve DoD’s performance standards, responsible manufacturers would proceed accordingly.”

His letter continued, “Under the SPS, GPS manufacturers were, in effect, granted a 4 MHz guard band of protection from the allocated band edge. Had the GPS manufacturers been responsible, they could have built to these standards, as other spectrum users have built to much tighter standards in heavily used frequency bands. But most of them avoided that responsibility.”

That line of reasoning is, not unexpectedly, dismissed by those with long experience with GPS, including the processes by which the SPS documents were created.

“The IS and PS documents are . . . a definition of what the GPS satellites provide,” says Tom Stansell, an expert in the field and long-time GPS consultant. “They were never intended to require manufacturers to design a certain way, other than they must design for message formats, signal levels, spreading codes, etc. The idea of ‘guard bands’ was never intended.”

In a press statement, The Coalition to Save Our GPSS said, “LightSquared has completely mischaracterized the 2008 DoD GPS Signal in Space (SIS) standards. In fact, DoD specifically said that the receiver characteristics it detailed ‘are not intended to impose any minimum requirements on receiver manufacturers or integrators,’ and they do not specify commercial GPS receiver performance standards.”

In an August 1 filing with the FCC, Stansell suggested that part of the problem arising from the fact that “communication and navigation are fundamentally different.” Navigation accuracy is not based on data demodulation, as packet-based communications are, but rather based on “pseudorange” measurements, “which are obtained by measuring the time of arrival of spreading code transitions.”

Achieving higher positioning accuracy generally requires wider bandwidth and better signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios. Consequently, Stansell pointed out, “The LightSquared demand to reduce RF bandwidth and allow GPS S/N to be degraded by up to 6 dB would be devastating to accuracy.”

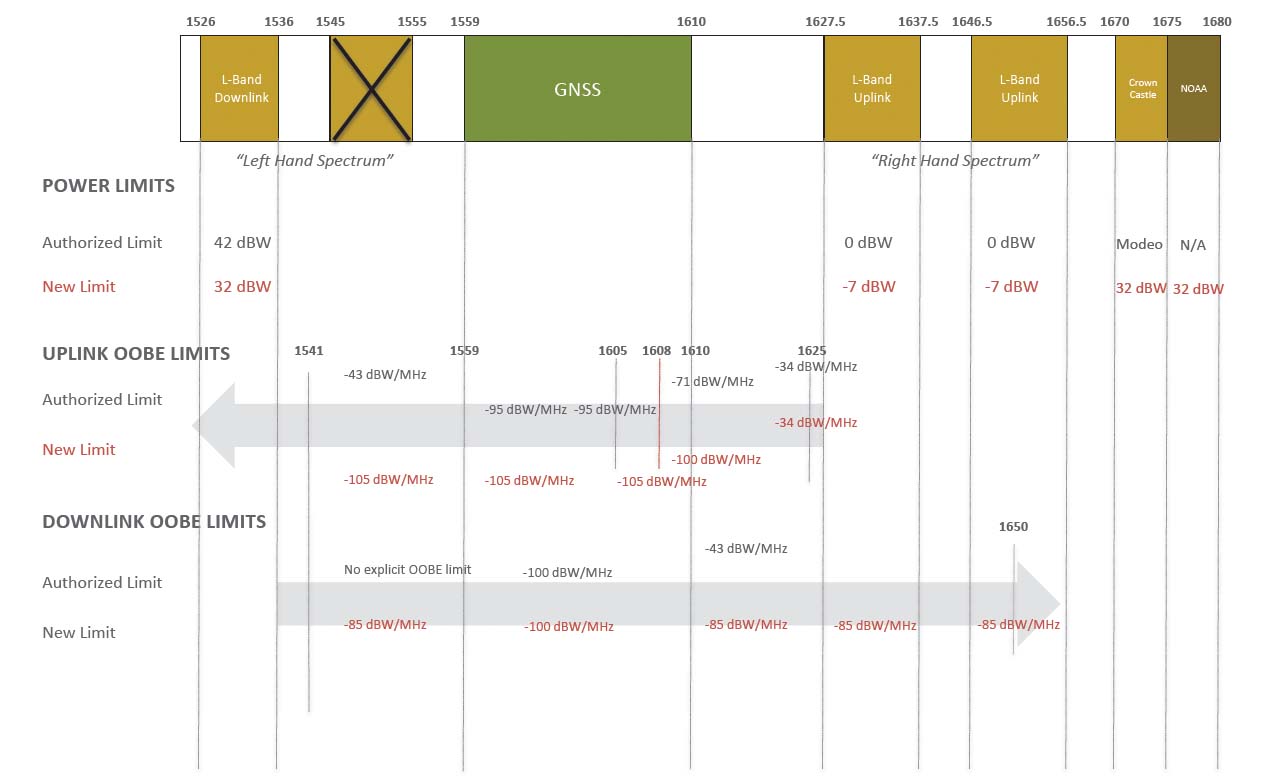

Stansell suggested that “the crux of the issue” is the transformation of the mobile satellite service (MSS) in the 1525–1559 MHz band from MSS use — with an option for ancillary terrestrial components (ATCs) that only relayed narrowband MSS signals to a limited number of users in urban environments — into a 100 percent terrestrial network with no requirement for handsets to be able to talk to satellites.

“As one who was part of the industry and as a consultant to both government and industry, no one expected such a transition,” Stansell added. “No one expected the FCC would change the use of that band from narrowband downlinks from satellites to a high power wideband terrestrial network.”

In other developments, on August 10, Julius Knapp, chief of the FCC Office of Engineering and Technology, asked LightSquared to respond to a series of questions about the results of receiver testing conducted by a Technical Working Group, including the frequency response of the RF front-end for all GPS devices tested, as well as production and U.S. sales information, estimated owner-use lifetimes, and application market information.

The agency also asked for an updated plan for the company’s deployment of base stations under LightSquared’s revised proposal to temporarily use only the lower 10 megahertz segment of downlink spectrum. Responses to the questions are due August 22.