A deadlock over 5G implementation, and the potential hazards the technology would create for air traffic safety, has been at least temporarily resolved. Not all questions have been answered nor problems eliminated, however. And while radio altimeters do not use GPS or GNSS technology, they are definitely PNT devices, and this situation could create precedents for ongoing and future conflicts between telecom and PNT use of the finite radio spectrum.

Almost two years into the pandemic, virtual collaboration and connectivity remains critical to sustaining remote workplaces, school learning and personal relationships globally. The situation has accelerated the urgency of deploying 5th Generation (5G) broadband cellular networks to increase capacity to connect to more devices simultaneously with fewer lags and quicker downloads.

But deadlines for 5G implementation have been pushed, and forward movement stymied, as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and a growing number of aviation industry voices warn of potential of 5G interference with radio altimeters, which measure the height of an aircraft above terrain immediately below it. This column addresses how we got here and what occurred just as this magazine was preparing for press.

Moving FAST?

The current administration has made 5G a linchpin of its sustainable infrastructure and clean energy platform. It even proposed a $65 billion investment in “broadband for all” as part of its $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill. However, launching 5G has been a high priority in the United States for years.

Under former Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Ajit Pai, the agency released a comprehensive strategy to Facilitate America’s Superiority in 5G Technology (the 5G FAST Plan), emphasizing the need to set aside spectrum in the low-, mid- and high-frequency bands for commercial, flexible use and unlicensed use. Its three key components included:

• pushing more spectrum into the marketplace

• updating infrastructure policy

• modernizing outdated regulations

Pushing more spectrum into the marketplace has fomented the current quagmire. The FCC plans to release almost 5 gigahertz of 5G spectrum into the market, which is more than all other flexible-use bands combined.

In 2016, the FCC commenced its first-ever broadcast incentive auction to make low-band airwaves available for wireless broadband. That auction, which closed in March 2017, repurposed 84 megahertz of spectrum, 70 megahertz for licensed use in the 600 MHz band and another 14 megahertz for wireless microphones and unlicensed use. The auction netted $19.8 billion in revenue, including $10.05 billion for winning broadcast bidders and more than $7 billion deposited with the U.S. Treasury for deficit reduction.

The follow-on Spectrum Frontiers proceeding, which remains ongoing, focused on 3,400 megahertz of high-band spectrum in the 37 GHz, 39 GHz and 47 GHz bands. As part of this initiative, the FCC auctioned a total of 1,550 megahertz of high-band spectrum for purposes of commercial use. The 2018 tranche involved the 28 GHz band; the 2019 auction, the 24 GHz band.

Congressional mandates in the 2018 Making Opportunities for Broadband Investment and Limiting Excessive and Needless Obstacles to Wireless Act (MOBILE NOW Act) directed the FCC to evaluate the feasibility of commercial wireless deployments in the mid-band at the 3.7–4.2 GHz range. In furtherance of this, the FCC has focused on the upper 37 GHz, 39 GHz and 47 GHz bands.

In 2020, it adopted new rapid public auction rules to make 280 megahertz of mid-band spectrum available for flexible use. The FCC allocated the 3.7–4.0 GHz portion of the C-band for mobile use, set aside 280 megahertz (3.7–3.98 GHz) to be auctioned for U.S. wireless services and allocated another 20 megahertz (3.98–4.0 GHz), a guard band for existing satellite operations, to be repacked into the upper 200 megahertz of the band (4.0–4.2 GHz).

In February 2021, upon completion of the auction of the 3.7–3.98 GHz frequency band, the FCC issued licenses to several wireless network providers conditioned on a phased deployment starting in the lower 100 MHz of the band (3700–3800 MHz) in 46 markets, with a target deployment date of December 5, 2021. In all, the telecoms paid about $80 billion to play.

The current controversy surrounds this mid-level C-Band, which is ideal for next-generation wireless broadband. Unlike high-band, it has favorable propagation characteristics. Compared to low-bands, it possesses the needed characteristics for additional channel re-use.

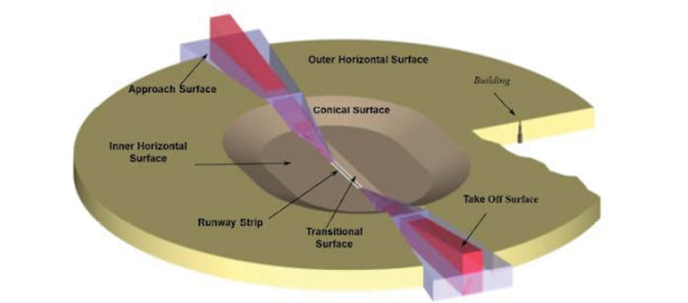

The problem is that aviation radio altimeters, which measure height by timing how long it takes a beam of radio waves to travel to ground, reflect and return, operate between 4200–4400 MHz. The concern is wireless broadband operations in the 3700–3980 MHz band may interfere with these radio altimeters.

Risk of Potential Adverse Effects

On November 2, 2021, the FAA issued a Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin (SAIB) AIR-21-18, Risk of Potential Adverse Effects on Radio Altimeters, recommending radio altimeter manufacturers, aircraft manufacturers and operators and pilots take a host of actions and voluntarily submit feedback to the FAA, FCC and National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA).

Among other things, the FAA asked manufacturers to “complete analysis or testing of each model number either in production, supported, or still being employed, to determine the susceptibility to interference from fundamental emissions in 3700–3800 MHz…and the full 3700–3980 MHz band…as well as potential spurious emissions in the 4200–4400MHz band, and assess this susceptibility for compatibility with the adjacent spectrum environment.” Pilots and operators must “remind passengers to set all portable electronic devices in the cabin and any carried on the aircraft to a non-transmitting mode or turn them off.”

In November, under pressure to do something while still publicly disagreeing that aviation interference is an issue, key spectrum auction winners AT&T and Verizon delayed their launch of commercial wireless services in the C-Band until January 5. The two also agreed to take additional mitigation measures during the first six months of 2022, including generally lowering power levels nationwide on 5G cell towers and placing even more stringent limits near regional airports and public helipads.

The aviation community continued to advocate further delays.

Agreeing to Disagree

The trade association that represents the U.S. wireless communications industry, the CTIA, has naturally aligned with the telecomms.

In an ex parte letter to the FCC Secretary, the CTIA noted, “Nearly 40 countries have already adopted rules and deployed hundreds of thousands of 5G base stations in the C-Band at similar frequencies and similar power levels—and in some instances, at closer proximity to aviation operations—than 5G will be in the U.S. None of these countries have reported any harmful interference with aviation equipment from these commercial deployments…”

The major airlines and the aviation trade associations disagree. The Helicopter Association International (HAI) stated, “It is falsely believed that since there has been no noted 5G interference in other countries, U.S. aviation safety won’t be compromised by deployment. This statement is misleading because the deployment details and maximum power levels in a variety of other countries aren’t the same as those planned in the United States.”

HAI explained that some countries, such as Japan, where 5G is deployed up to 4.1 GHz at power levels for 5G that are at least 90% below those permitted in the U.S., have reduced the potential for aviation equipment interference. Generally, in Europe, according to HAI, 5G is deployed in the 3.4 to 3.8 GHz band, also at power levels “well below the permitted power levels in the United States” with an amount of separation from adjacent bands at 100 MHz greater than authorized in the States. France, specifically, has implemented 5G “exclusion zones” to protect public safety. Finally, Australia operates even farther away from radio altimeter RF bands at power levels 76% lower than allowable here.

In an Aviation Safety Proposal for 5G Limits, the aviation industry recommended the FCC adopt technical, regulatory and operational mitigations similar to what some of these other countries have instituted.

Major airlines such as United and Southwest indicated during a mid-December U.S. Senate Commerce Committee hearing on airline oversight that the January 5G rollout, without a viable interference fix, would negatively impact radio altimeters at 40 or more of the country’s largest airports. This, they noted, could potentially impact 4% of daily flights, resulting in delays, diversions or cancellations to the detriment of hundreds of thousands of passengers. United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby has been quoted as saying, “It is a certainty. This is not a debate.”

Helicopters also face significant challenges. Nineteen aviation and aerospace companies and associations told the FCC in August that, absent mitigations to protect radio altimeters, flexible base use stations at large medical centers with multiple heliports would “have the potential to wreak havoc on the use of heliports at hospitals and in medical centers, as well as at the countless random offsite locations where helicopters frequently land in first responder situations.” More than 550,000 patients in the U.S. use air ambulance services every year.

The Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA), a not-for-profit corporation that develops consensus-based recommendations on contemporary aviation issues, agrees there is cause for concern. The kicker is that it has been sounding the warning alarm for more than a year.

New Fuel on An Old Fire

In October 2020, RTCA issued Paper No. 274-20/PMC-2073, Assessment of C-Band Mobile Telecommunications Interference Impact on Low-Range Radar Altimeter Operations.

Using technical information provided by mobile wireless industry and radar altimeter manufacturers, the RTCA tested several representative radar altimeter models to empirically and quantitatively evaluate their performance tolerance to expected 5G RF interference signals in the 3.7–3.98 GHz band. It developed models and assumptions to predict the received interference levels across a wide range of operational scenarios and compared them to empirical tolerance limits. It also studied two real-world operational scenarios for civil aircraft in which the presence of the expected 5G interference will result in a direct impact to aviation safety, as part of its detailed risk assessment.

The bottom line from its 231-page report: “The results . . . reveal a major risk that 5G telecommunications systems in the 3.7–3.98 GHz band will cause harmful interference to radar altimeters on all types of civil aircraft—including commercial transport airplanes; business, regional, and general aviation airplanes; and both transport and general aviation helicopters.” Possible consequences:

• Loss of Situational Awareness: Erroneous or unexpected behavior of radar altimeters leads to a loss of situational awareness for the flight crew and a risk of task saturation for the crew, who must compensate for the lack of reliable height information using other sensors and visual cues.

• Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT): Crashing the plane, which almost always results in aircraft hull loss, with a high likelihood of loss of life or severe injuries.

• Other Specific Operational Impacts on Commercial Aircraft: Radar altimeters are also used as safety-critical navigation sensors by the auto flight guidance system that feeds into systems such as traffic collision avoidance systems/airborne collision avoidance systems, predictive windshear systems, and terrain avoidance and warning systems.

In 2019, Texas A&M University’s Aerospace Vehicle Systems Institute (AVSI), an aerospace industry research cooperative, conducted an analysis for the FCC. AVSI’s “Preliminary Report: Behavior of Radio Altimeters Subject to Out-Of-Band Interference” found that for all three altitude scenarios tested, 200 feet, 1,000 feet, 2,000 feet there was “a clear performance difference in altimeters as an increasing amount of out-of-band interference (OoBI) was received by the radio altimeters from the 3700–4200 MHz band.”

Most of the altimeters reported broadly consistent susceptibility to OoBI power spectral density (PSD) levels until more than approximately 200 to 250 MHz of OoBI was introduced (starting at the 3700 MHz band edge). At that point, the acceptable levels of PSD began to decrease as OoBI spectrum occupancy increased toward the 4200 MHz band edge.

In February 2020, AVSI issued a supplemental report conceding that the majority of radio altimeters demonstrate some resilience to OoBI. However, the report noted, “this does not guarantee absolute protection from any signals in the 3700–4200 MHz band.”

The White House Steps In

United’s Kirby has said the FCC and FAA “need to get in a room and talk to each other and solve the problem,” adding that the issue “cannot be solved on the back of airlines.” That happened after the White House got involved.

In mid- December, White House National Economic Council director Brian Deese met with FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg on the 5G aviation issue. Subsequent negotiations among government, aviation and telecoms produced an agreement issued on January 3: deadlines for 5G deployment, slated for January 5, were rolled back for another two weeks.

President Joe Biden stated “This agreement ensures that there will be no disruptions to air operations over the next two weeks and puts us on track to substantially reduce disruptions to air operations when AT&T and Verizon launch 5G on January 19th.”

According to FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel, the agreement “provides the framework and the certainty needed to achieve our shared goal of deploying 5G swiftly while ensuring air safety.”

A letter the FAA submitted to the FCC on New Year’s Eve submitted the proposed new safety framework. Under the agreement, commercial C-band service would begin as planned in mid-January with certain exceptions around priority airports, around which buffer zones would be placed until the FAA completed its assessments of interference potential and identified appropriate mitigations. The FAA said it would safely expedite the approvals of Alternate Means of Compliance for operators with high-performing radio altimeters to operate at those airports.

The parties hammered out the final terms of the deal in a document published on January 3 (www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/2022-01/USDOT%20Letter%20to%20ATT%20Verizon_20220103.pdf).

True to the original proposal, the deal required the FAA to provide a list of no more than 50 airports subject to C-Band exclusion zones. The telcos would honor their voluntary commitments to the DOT to hold off full deployments around these priority locations through July 5, after which 5G base stations would be potentially unconditionally deployed. Generally, all parties agreed to work together collegially through information-sharing and ongoing dialogue. The FAA agreed not to seek additional delays beyond July.

On January 7, 2022, the FAA announced it had selected the 50 airports for these “5G buffers,” based on their traffic volume, the number of low-visibility days and geographic location. Among others, not surprisingly, the list includes Dallas-Fort Worth International, John F. Kennedy International and Los Angeles International.

The FAA has also erected an entire webpage dedicated to “5G and Aviation Safety” (https://www.faa.gov/5g), where it lists handy resources and provides Q&As.

Will additional concerns surface or mitigations be required? Only time will tell. Secretary Buttigieg wrote to the AT&T and Verizon CEOs on January 3, “We are confident that your voluntary steps will support the safe coexistence of 5G C-Band deployment and aviation activities, helping to retain America’s economic strength and leadership role around the world.”