Lawmakers are poised to sharply limit the ability of foreign nations to own or control satellite system monitoring stations on U.S. territory, a rare show of congressional cooperation triggered by a Russian request to place stations supporting its satellite navigation system on American soil.

Lawmakers are poised to sharply limit the ability of foreign nations to own or control satellite system monitoring stations on U.S. territory, a rare show of congressional cooperation triggered by a Russian request to place stations supporting its satellite navigation system on American soil.

The House and Senate announced December 9 that they had agreed on language in the 2014 Defense Authorization Act to require the president to obtain certification from the secretary of defense and the director of national intelligence before authorizing construction in the United States of a GNSS monitoring station that would be directly or indirectly controlled by a foreign government. The two officials must jointly certify to Congress that the ground monitoring station will not possess the capability or potential to be used for the purpose of gathering intelligence in the United States or improving any foreign weapon system.

The certification may be waived if both the defense secretary and national intelligence director agree that it is in the best interests of the United States and meets the following conditions: the data collected and sent is not encrypted, the station is not located near a national security site, and does not pose a cyber-espionage or intelligence threat.

The measure, which has already been approved by the House, sunsets after five years. The U.S. Senate is expected to taken up the Authorization Act Wednesday (December 18, 2013) according to the National Journal magazine.

The Russian proposal for GLONASS monitoring stations was originally viewed favorably by NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration, which were interested in acting as hosts,” Ken Hodgkins, director of the State Department’s Office of Space and Advanced Technology told the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board during their December 5 meeting in Washington.

Russia has sought to deploy monitoring stations abroad for some time. In addition to 14 GLONASS monitoring stations in Russia, sites have been established in Brazil and Antarctica at Russia’s Bellingshausen station, according to Russian officials. Additional foreign GLONASS monitoring stations will roll out soon, including additional sites in Brazil and Antarctica, as well as Australia, Cuba, Indonesia, Spain, and Vietnam.

The idea of sites in the United States has triggered a strong reaction from U.S. defense and intelligence officials, however, who see such installations as a possible conduit for espionage.

Congressional Objections

Members of Congress also questioned whether the United States should be helping improve the accuracy of Russian weapons or assisting a possible competitor to the U.S. Global Positioning System.

“It is clear Russia’s interests are not often aligned with those of the United States,” said Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., when he moved to amend the Defense Authorization Act to limit foreign monitoring stations. “I am deeply concerned and people within the intelligence community are deeply concerned and people within the Defense Department are deeply concerned about the Russian proposal to use U.S. soil to strengthen Russia’s GPS capabilities. These ground monitoring stations could be used for the purpose of gathering intelligence. Even more troubling, these stations could actually improve the accuracy of foreign missiles targeted at the United States.”

Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Alabama, told Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel in a November 13 letter that he was worried the stations might interfere with GPS signals or signals from other important systems. He also wanted to know “why the United States would be interested in enabling a GPS competitor, like Russia’s GLONASS, when the world’s reliance on GPS is a clear advantage to the United States on multiple levels.”

Russian officials now largely view the proposal to be unworkable, a source, speaking on background, told Inside GNSS. Although officially U.S. officials continue to review the request — and general, informal talks with Russian officials are ongoing — no discussions on the monitoring station proposal specifically have taken place for many months, another source confirmed.

May Turn to International GNSS Service

Hodgkins told the advisory board that GLONASS managers are now likely weighing a different approach.

“[The Russian’s] thinking has evolved to a point where they probably aren’t looking at stations on U.S. territory but at utilizing other receivers that are there, maybe through the IGS [International GNSS Service] system,” he said.

In operation for more than 20 years, the IGS is a volunteer organization of more than 200 individual agencies and institutions that currently maintains a global network of 368 active GNSS monitoring stations and a long-term tracking data archive as well as products derived from the analysis of these measurements. The IGS Central Bureau is located at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which ensures access to IGS products and information. An international governing board oversees all aspects of the IGS.

Some 140 of the active IGS stations provide GLONASS data as well as GPS, according to a presentation by Urs Hugentobler, chair of the IGS governing board, at a meeting in Vienna earlier this year. On April 1, 2013, the IGS launched its Real-Time Service (RTS) for GLONASS as a beta service with full operational capability expected by the end of this year. The RTS will provide free access to and free use of real-time GLONASS orbital ephemerides and clock products.

It would be possible to use the real-time GLONASS observations collected by IGS to improve instantaneous estimates of the onboard clock offset, said Oliver Montenbruck, who heads the GNSS Technology and Navigation Group at the German Aeronautics and Space Research Center (DLR), German Space Operations Center (GSOC) and chairs the IGS GNSS Working Group. “Technically this can well be done with the present IGS network and the IGS is in fact itself monitoring GLONASS clocks in this way,” he told Inside GNSS via email.

The main difference between using the IGS service and setting up a proprietary Russian monitoring station, said Montenbruck, is the service and availability guarantee, “which IGS (as a volunteer organization) is not able to offer.”

Opposition Runs Counter to Cooperative GNSS Efforts

Objections from U.S. defense and intelligence officials and voices in Congress contrast with the long-established multilateral efforts of the IGS and the International Committee on GNSS (ICG) — as well as bilateral cooperation between the United States and various other GNSS providers — to increase the interoperability of GNSS systems.

Indeed, the ICG has launched an International GNSS Monitoring and Assessment Service (iGMAS) initiative, and the IGS is well along with its Multi-GNSS Experiment (MGEX), which seeks to transition the IGS to a multi-GNSS global tracking network that can provide fully combined and consistent multi-GNSS products. Montenbruck and IGS colleagues will author an article on the MGEX in the January/February 2014 issue of Inside GNSS.

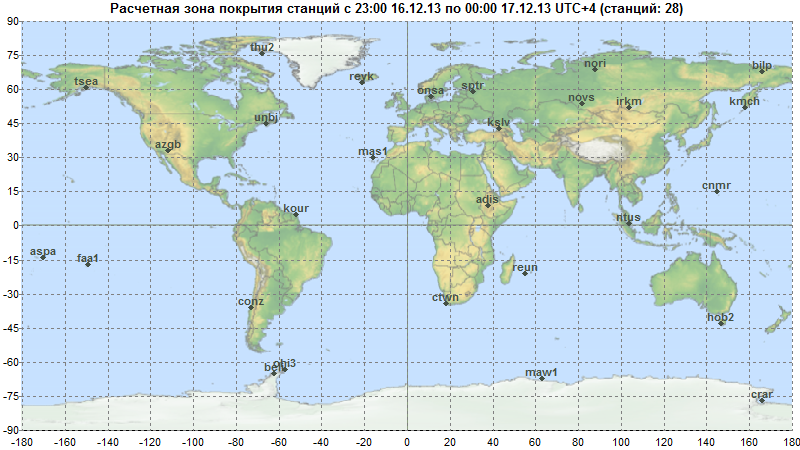

Richard Langley, professor of geodesy and geomatics engineering at Canada’s University of New Brunswick, pointed out to Inside GNSS that the Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos) already uses sites in Alaska and Arizona for monitoring the status and health of the GLONASS constellation on an hourly basis — “but not for orbit determination as far as I know.” According to the accompanying map from the Roscosmos Information-Analytical Center website, additional GLONASS monitoring sites on U.S. territory include Pago Pago, Saipan, and Thule Air Base.

The original Russian proposal to the United States was made in May 2012 and was for stations tasked with monitoring the quality of the GLONASS signal as opposed to stations that would have been an integral part of the management of the GLONASS constellation, said an expert familiar with the issue. The proposal, however, did not include key specifics such as where the stations would be located.

Hodgkins said during his presentation that the Russians have also not provided an element essential to establishing a monitoring station — a written civil signal performance standard

“We don’t really know what it is that they are trying to achieve,” said Hodgkins.

The State Department is continuing to talk with the Russians “on a very informal basis,” Hodgkins told the PNT advisory board, “primarily to make the point that we really need more information and a better sense of what they need from a performance monitoring standpoint.”

The United States was one of some 30 countries approached by the Russians to host monitoring stations, said Hodgkins. Australia was among those asked to provide sites for monitoring stations, said Matt Higgins, who represents the Australian-based International GNSS Society on the board. His country’s officials, he said, also have had problems obtaining a written signal standard.

“It has been difficult to get a written description of exactly what is required,” said Higgins.

Higgins added that Australia would like to see a standard for monitoring systems developed by the ICG and then used to build common stations for use by multiple systems.

“It would be much better to have shared stations,” he said, with an internationally-agreed-to format.