The convergence of mobile communications, information, and navigation technologies is driving the need to re-examine interference and jamming issues within a broader national and international cybersecurity framework, a U.S. homeland security official told a recent conference on GNSS vulnerability.

The convergence of mobile communications, information, and navigation technologies is driving the need to re-examine interference and jamming issues within a broader national and international cybersecurity framework, a U.S. homeland security official told a recent conference on GNSS vulnerability.

“Intentions and actions to deny, degrade, disrupt, or destroy information, information systems, or the services they provide, could fall within the purview of cybersecurity,” says Robert Crane, senior homeland security advisor for the National Coordination Office for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation and Timing (NCO PNT), told a audience at the GNSS Vulnerabilities and Solutions Conference in Croatia last month.

“We are talking about intentionally preventing information/data from traveling through the spectrum,” Crane added. “Therefore, I would argue that jamming, ‘spoofing’ or other forms of intentional interference to such movement in the electromagnetic spectrum should be viewed as cyber disruptions.”

That could have the effect of increasing attention given to GPS interference concerns. “Senior leaders across the U.S. government are aware of the potential impact of such interference,” told conference attendees. “They continue to consider the risks when developing policy, doctrine, and courses of action.”

Meanwhile, a prospective interference detection and mitigation (IDM) system known as Patriot Watch was scheduled to get a closer look during civil-oriented field tests and training this week (June 18–22, 2012) at White Sands Missile Range. A Department of Homeland Security (DHS) assessment of the risks and effects of GPS disruptions on U.S. critical infrastructure, with a draft report completed last November, has failed to reach the light of day.

Although the nation has so far avoided a catastrophic incident caused by GNSS interference, incidents are increasing along with the risk of more purposeful actions by adversaries.

“Collectively, we have all been fortunate from a positioning, navigation and timing, or PNT, perspective over the last couple decades in facing relatively unsophisticated adversaries with either limited access to or limited desire to routinely employ interference or disruptive technologies,” Crane said.

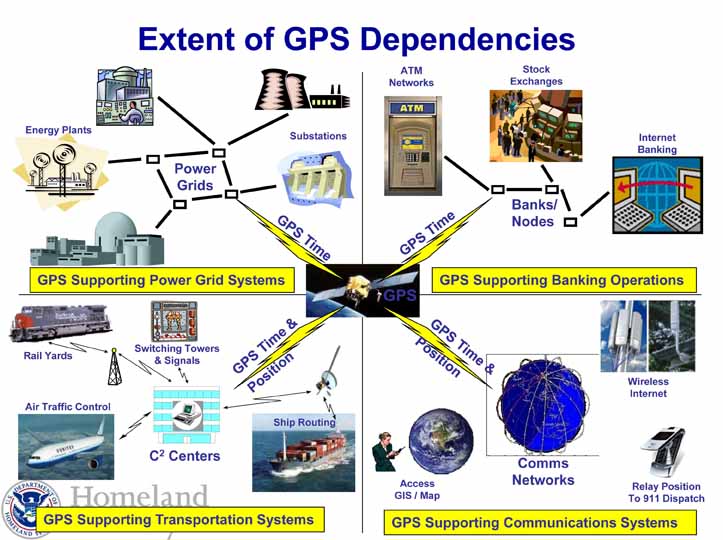

The growing risk is driven by two major trends: the evolution of integrated mobile technologies and greater reliance on spectrum for wireless communications linking voice, video, text, Internet, position, and data services, and worldwide proliferation of capabilities to disrupt vital networks. “The evolution brings changes in the risk profile of the communications, information, and navigation infrastructure,” he said.

“Traditionally we have limited our consideration of GPS signals within the context of radionavigation frequency spectrum assignments,” Crane said. “Instead, we need to start thinking of it more broadly as another wireless technology (one of many) and use the tools and techniques to monitor, protect, and share information that we do for broadcast signals or cell phone interference.”

A more forward-looking perspective “links intentional and unintentional GPS signal interference — including jamming and signal imitation, or spoofing — to the broader potentiality of radio frequency interference within the larger, integrated mobile environment that includes wireless voice, video, data, text, and Internet services,” according to Crane.

Crane said that discussions in Washington over the last year have examined the relationship between GPS interference and wireless within the existing cybersecurity framework.

“[I]t has become difficult to reach agreement on how to define cyberspace due to the complexities of the information and communications networks and the roles of government and the private sector,” he said. “The nature of cyberspace and its dependency on the radio spectrum will continue to grow as time and technology progress. Aligning spectrum issues with the cyber domain will help to broaden the range and scope of our real-time monitoring, analytics, and situational awareness.”

Crane argues that the United States, independently as well as in cooperation with other nations, should try to manage GNSS interference “in near real-time with continuous monitoring, reporting, and sharing of interference information and build a common operating picture that improves situational awareness and response within the broader cyber domain.”

Despite the GNSS community’s heightened awareness of the need for interference detection and mitigation (IDM), however, the lead agency charged with responsibilities for assuring the protection of PNT capabilities 2004 National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD-39)— DHS — has lagged in efforts to do so. Most recently, a DHS study of GPS vulnerability under way for nearly two years, “National Risk Estimate: Risks to United States Critical Infrastructure from Global Positioning System Disruptions,” has reportedly been filed away at the agency without distribution.

Brandon Wales, director of the Homeland Infrastructure Threat & Risk Analysis Center, told the PNT Advisory Board last November that the final report would be finished up by January and an unclassified version should become available. The agency assessed the disruption risk to four sectors: communications, emergency services, energy and transportation.

IDM remains essentially an unfunded mandate for the department, which nonetheless has pushed the agenda item incrementally forward during the seven-plus years since NSPD-39’s issuance. That effort has taken its most tangible form in the Patriot Watch/Patriot Shield/Patriot Warrior initiative, a still largely conceptual system design for monitoring, detecting, analyzing, locating, and responding to GPS jamming.

According to John Merrill, manager of the DHS PNT Program Management Office, the White Sands Missile Range exercise, supported by the U.S. Air Force 746th Test Squadron, will include a demonstration of Patriot Watch capability and a variety of test scenarios incorporating the first open-air transmissions of commercial GPS jammers.