Future of air traffic control (FAA image)

Future of air traffic control (FAA image)A public-private partnership created to reduce the financial burden involved in implementing the nation’s GPS-based, next-generation (NextGen) air transportation system has raised its first rounds of financing and is now negotiating contracts with its charter customers.

“We have . . . closed our first tranche of equity,” said Jim Hughey, senior vice-president of the NextGen Equipage Fund. The fund has secured a total of $100 million in commitments with some $40 million of that coming from leading aerospace companies.

A public-private partnership created to reduce the financial burden involved in implementing the nation’s GPS-based, next-generation (NextGen) air transportation system has raised its first rounds of financing and is now negotiating contracts with its charter customers.

“We have . . . closed our first tranche of equity,” said Jim Hughey, senior vice-president of the NextGen Equipage Fund. The fund has secured a total of $100 million in commitments with some $40 million of that coming from leading aerospace companies.

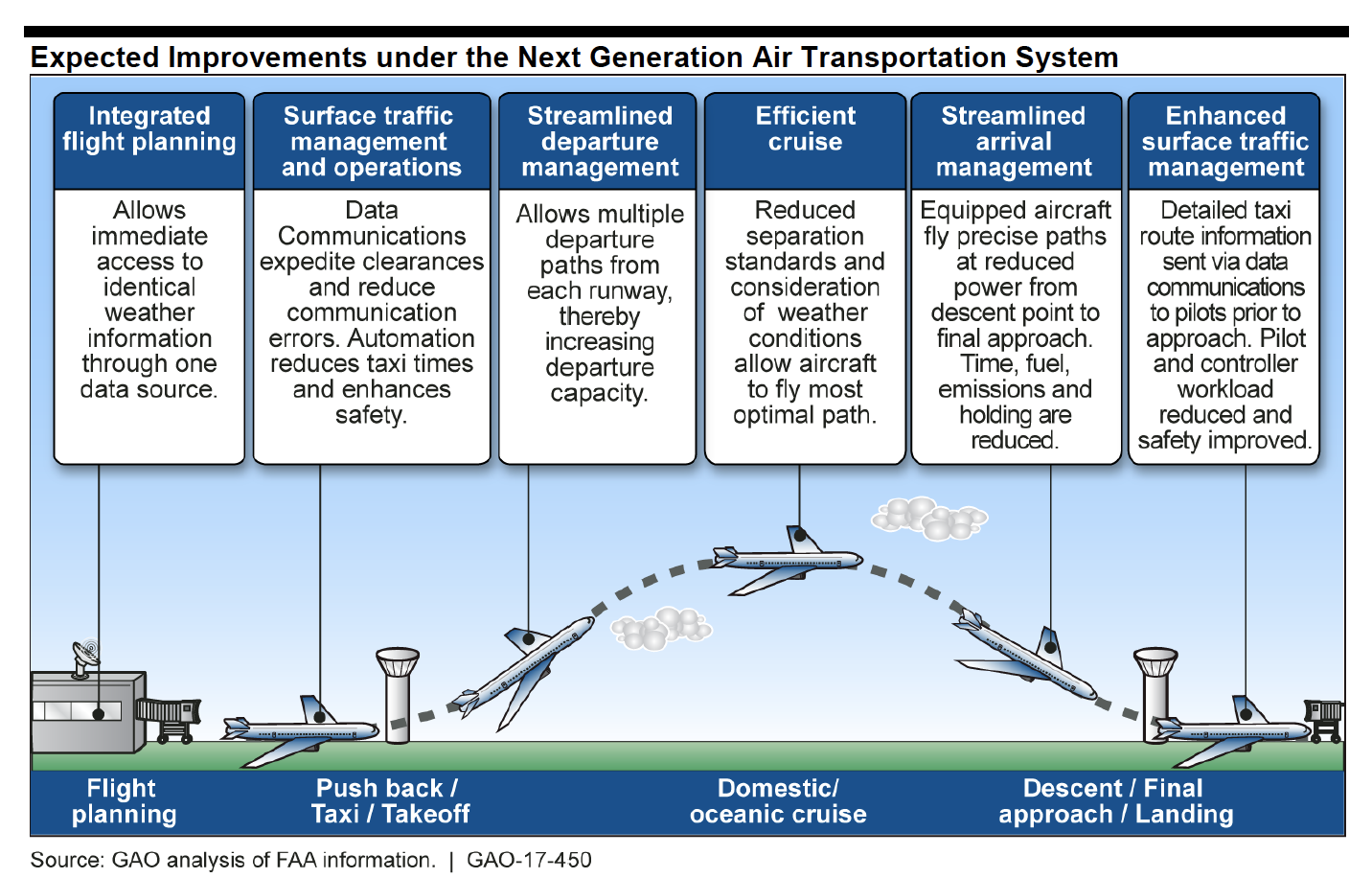

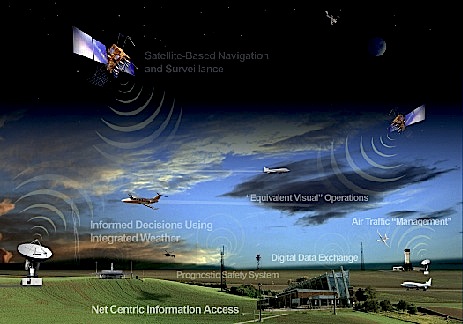

The fund is a channel for airlines and air carriers to tap federally supported loans. The loans support the purchase of the hardware and services needed to equip aircraft to use NextGen, an upgrade to air traffic surveillance, control, and communications being developed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

In the works since 2003, NextGen is widely seem as crucial to handling the growth in demand for air travel over the next decade. The U.S. air transportation system now moves some 730 million passengers and supports roughly 70,000 commercial and general aviation flights every 24 hours, according to a brief prepared by the House Aviation Subcommittee for a NextGen status hearing on September 12.

The FAA expects the number of passengers to reach 1 billion by 2025 with more than 95,000 flights every day, according to the General Accountability Office (GAO) — a level of activity widely acknowledged to be unsupportable with the nation’s current infrastructure.

Fly Now, Pay Later

The equipage fund raises money that it uses to buy the equipment needed for airlines to update their planes and systems. It then installs the equipment and helps keep it up to date. The airline or air carrier pays for the equipment and service over time, avoiding an up-front financial hit.

Because the government is guaranteeing the loans, the cost of the capital is low, explained Hughey. The fund leverages the money from private investors into much larger purchases of equipment multiplying its effect. Hughey said the $100 million raised so far, which is at risk, is expected to fund $1 billion in equipment. The revenue to pay off the equipment purchases/installation comes from the airlines’ payments made over time.

From the government’s point of view, the approach is intended to speed adoption. The real cost savings from NextGen don’t occur until a critical mass of the industry, an estimated 60 percent, adopts the new system. That suggests that those who wait to equip until most others have already done so will be at an advantage: they get the offsetting savings sooner after investing in the equipment as opposed to sitting, unrewarded, on sunk costs for an extended period of time.

The fund, however, may be able to change that calculation. It offers a lower-cost way to finance the equipment but, since its resources are likely to be limited, those airlines that do not move quickly may get left out. That creates an incentive to adopt early — and some firms are already moving to take advantage of the fund.

“We are a proceeding now with our first commercial contracts with our customers, which are a couple leading airlines,” Hughey told Inside GNSS. “They will be the charter customers for the fund.”

Although the fund is not expected to be able to finance all of the billions in equipment upgrades that will needed to take advantage of NextGen, it may expand its efforts.

“If we are successful in placing the full $1 billion in capital that is leveraged off the $100 million, then we would be very interested in doing a larger portion.” It would likely take several years to place the first round of capital, Hughey said.

Political, Administrative Obstacles

The legal basis for the fund and the federal loan guarantees was put into place in February with the passage of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012. The bill set forth a number of tasks for the FAA aimed at improving management accountability in the NextGen program, which is costing the agency some $1 billion a year.

The FAA’s implementation of that law and NextGen’s ballooning costs — especially for the key En Route Automation Modernization or ERAM program — came under fire during the Aviation Subcommittee hearing.

“If you were working for me and you had a $330 million to $500 million overrun (in ERAM), and a three- to four-year delay, your butt would be fired. That is not acceptable.” Rep. John Mica, R-Fla., the chair of the full House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee told Department of Transportation Deputy Secretary, John Porcari and Acting FAA Administrator Michael Huerta.

The FAA has made changes, said Huerta, including restructuring its NextGen contract. Some things also are not currently within FAA control, pointed out Porcari.

The FAA administrator, for example, is supposed to have a deputy directly overseeing NextGen. Though the role has been delegated to Vicki Cox, she cannot be put into place until Acting Administrator Michael Huerta is confirmed as administrator — and his confirmation has been hung up since March. The reauthorization bill also calls for appointment of a Chief NextGen Officer. The lack of confirmation is holding up that new position as well.

“There is a chain of command issue here,” said Porcari.

Porcari also assured the committee that the United States was working with the European Union to ensure that their version of NextGen, which is called SESAR (Single European Sky ATM Research), would be fully interoperable with the U.S. system. The United States is slightly ahead in its development of NextGen, witnesses told the committee, acknowledging that there is an economic advantage to having the lead in the development of a satellite-based air transportation system.

That lead was fragile, however, as was any hold on the jobs and exports linked to having the foremost system.

“We’re ahead — but just a little bit,” Gerald Dillingham, the director of GAO’s Physical Infrastructure Division, told the committee. “There’s a lot of cooperation but also some competition between the U.S. and Europe. I think what is important is that it could go off track at any time. If we fall behind implementing NextGen, and they keep moving, we could find ourselves in a different position.”

Implementation would fall behind should sequestration take place in January, Porcari said in response to a question from Rep. Jerry F. Costello, D-Ill.

Costello pointed to a report by the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) that said sequestration could push back full implementation of NextGen by 10 years or more to 2035 or beyond at a cost of some 1.3 million jobs and tens of billions of dollars in economic activity.

Porcari did not address the AIA report, saying it, and other reports, were based on very specific assumptions on which he declined to comment. He agreed, however that sequestration would delay NextGen — and the hit to the program would be worse than one might expect at first glance.

“If (sequestration) happens in January, we’re already a quarter of the way through the fiscal year; so, the impact would be greater because it is not spread over an entire year.”

Dee Ann Divis is an editor at the Washington Examiner in Washington D.C. She writes the Washington View column for Inside GNSS.