An overview of this navigation demonstration payload on IM-1 and a look at how a deployable local radio beacon infrastructure could enhance tracking precise locations on the Moon and in cislunar space.

EVAN J. ANZALONE, TAMARA L. STATHAM, NASA/MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER

With the recent heavy investment in missions targeting lunar space, both on the surface and in various orbits [1], cislunar space will be approaching a critical mass where the number of vehicles and support assets operating simultaneously is large enough that the desire for in-situ aids becomes preferable to independent fully Earth-centric operations. There have been previous studies on ideas like the Interplanetary Internet network [2] and concepts like LunaNet [3] that seek to build out a more robust network to enable multi-user compatibility and a shared backbone of data to/from Earth. This is not only for communication and data transport, but also areas such as navigation. The baseline approach for long-term lunar orbiting assets and for the Apollo missions was to use ground-tracking assets on Earth to provide updates to vehicles of the spacecraft’s position and velocity at a given time [4, 5]. While this approach is understood and implemented, it is limited by the number of available ground stations and support observations. Scenarios such as multi-spacecraft in aperture help to alleviate this impact, but with increasing missions requiring high data simultaneously, alternate solutions are needed for long-term sustainability and growth.

To address these limitations, there is a need for deployable local infrastructure that can provide an augmenting capability to other in-situ resources. The goal of the Lunar Node-1 (LN-1) payload is to demonstrate the first steps of this approach.

The Payload

The LN-1 payload was designed, built and tested at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. LN-1 provides a modular design, made with commercial of the shelf (COTS) components, that could be integrated into a variety of host vehicles and, with adequate power generation/storage, offer long-term operation. Figure 1 provides an overview of the implementation and size of the payload relative to the host lander. The left image shows a view of the Intuitive Machines NOVA-C lander Odysseus. LN-1 is located near the top of the vehicle to enable an unencumbered view of flight of the payload’s antenna back to Earth. The middle image provides a zoomed-in view of LN-1 itself, wrapped in multi-layer insulation with its large radiator visible. The right images provide insight to its primary flight components: the controller board housing the controller and space chip-scale atomic clock (CSAC), the power/interface board, which provides voltage regulation, electromagnetic interference protection and reverse voltage protection, as well as the Tethers Unlimited SWIFT-SLX S-band radio.

The payload’s main function is to exercise multiple approaches to signals that would be used by lunar infrastructure. The navigation modes tested included both the Multi-spacecraft Autonomous Positioning System (MAPS) and pseudo-noise(PN) based one-way non-coherent ranging and Doppler tracking to provide alternate approaches and comparisons for navigation performance. The MAPS concept of operations is shown in Figure 2. These concepts are described in more detail in [6]. In this concept, each spacecraft shares its timing and state knowledge as part of either system broadcasts or pre-programmed communication passes within the network. In this approach, the relays operating as trunks on each planetary network act as anchors, providing high accuracy timing and state references to other elements throughout the network. Digital information embedded into the communication packet standard allows for sharing navigation information as part of every communication link between assets.

Flight Operations Plan

A diagram of the LN-1 concept of operations is shown in Figure 3. LN-1 syncs its internal time and state to the lander’s, using its best estimate. All commanding and health and status will be relayed through primary payload telemetry. Over the course of the trans-lunar cruise and lunar surface operations, LN-1 will broadcast its state and timing information back to Earth for several observation passes to the Deep Space Network (DSN). Upon reception of this data, high accuracy packet reception timestamps will be used (along with atmospheric data for induced delays) to assess a ranging observation. This data will be captured across multiple passes to compute a navigation state of the payload over the mission. In addition to broadcasting telemetry, the payload will switch to a one-way PN ranging tone consistent with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s definition as in [7] to capture long-term stability and performance. Similarly, there are plans to include potential very long baseline array (VLBA) observations to provide a completely independent navigation solution. As such, Lunar Node-1 will be able to compare performance across multiple methods post flight, including: radiometric tracking based on the host vehicle and its landed state, LN-1 derived PN and Doppler observations, LN-1 time of flight measurements, and very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) angular observations.

Summary of operations and passes

The plan for LN-1 was to operate for an extended period of time from the lunar surface to capture long-term trends and evaluate calibration capability and time keeping to inform the operational cadence needed for this grade of hardware as a navigation aid. Being at a fixed known location on the lunar surface helps to provide a highly accurate truth model to calibrate timing delay, range and Doppler observations. As NASA contracted with Intuitive Machines to move the landing site to the South Pole region, the surface stay was reduced to seven to eight days because of the local conditions and time of year at the landing site. To maximize scientific return, it was intended for the payload to be turned on soon after landing to allow an extended period to thermally equilibrate while landing checkout procedures were complete, prior to an initial pass six to 12 hours later. Given these desirements, the team negotiated with DSN schedulers to maximize ground coverage time for the mission.

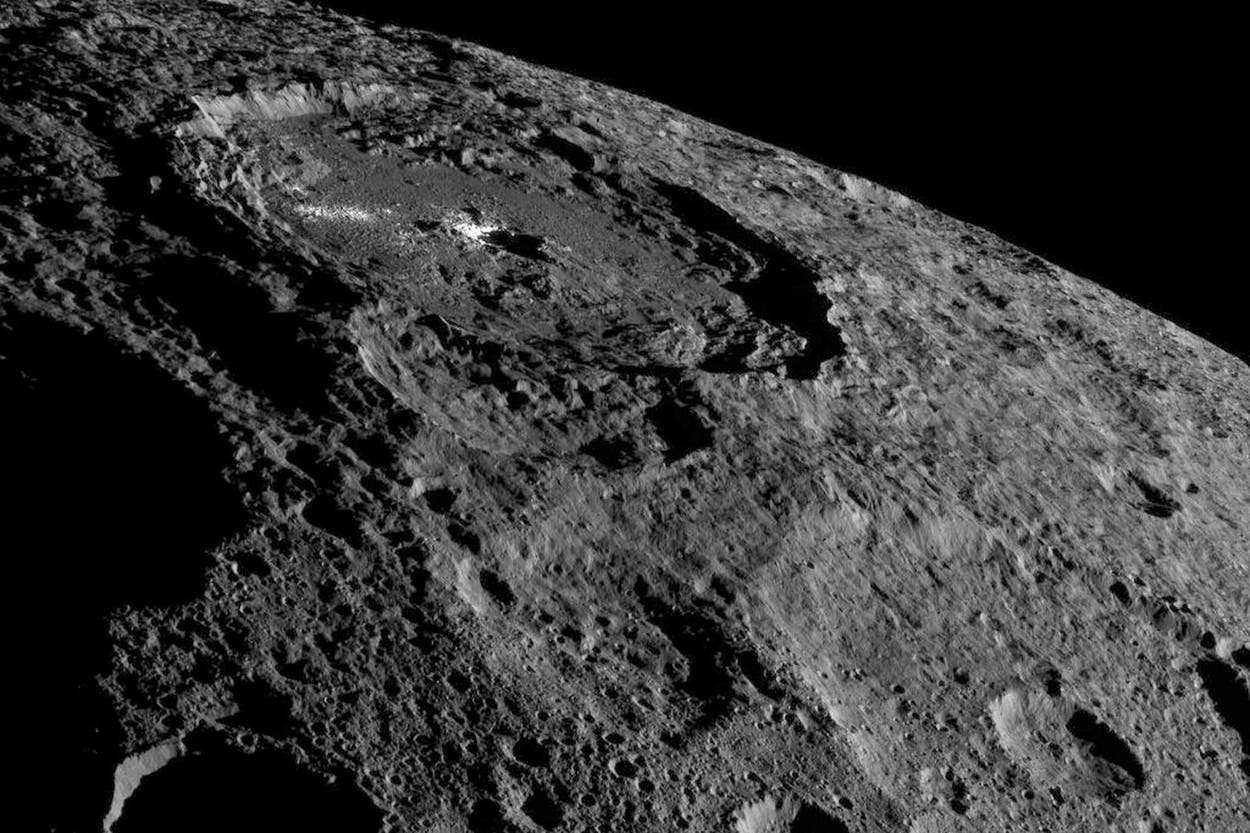

The cruise passes were essentially executed without issue and the team was able to execute the MAPS mode for each of these. The pass canceled was the team’s plan checkout of PN ranging prior to landing. The vehicle landed on the lunar surface on February 22, 2024. The landing site was verified by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The surface imagery is shown in Figure 4. The surface operations were limited due to the landing configuration [8] and time required to tweak the vehicle’s communication system, align assets, and adjust for ground weather conditions at the large receive dishes on Earth. Once the vehicle was in a stable and known state, the lander allowed for two LN-1 passes with ground sites. These occurred on February 27 and 28. To reduce operational burden and streamline commanding, a reduced command set was used to bypass normal procedures to quickly turn the payload on and enter a transmission state. Due to power constraints, each pass was limited to about 15 minutes each. This represented a minimum level of success that enabled the payload to operate from the lunar surface, verifying that it survived and capturing observations (both raw RF and processed MAPS and one-way PN ranging).

Overall, the payload was able to capture > 200 MB of tracking data (one-way Doppler of IM-1 and LN-1, two-way Doppler of IM-1) across the entire mission (cruise/surface). For LN-1, this amounts to ~4.5 hours of MAPS packets transmission received by DSN across four cruise passes (>40K one-way MAPS packets), 15 minutes of MAPS packet transmission from the lunar surface, 15 minutes of one-way PN ranging from the lunar surface, and multiple raw RF recordings of LN-1 transmissions by DSN to assess multipath and data processing. The team was not able to conduct radio frequency (RF) recordings at Morehead State (due to the pass scheduling of when LN-1 was transmitting) nor VLBI observations due to the last-minute scheduling and limited pass duration.

Payload performance

While the mission did not conduct extensive operations from the lunar surface, the payload did conduct limited daily operations, primarily in the MAPS telemetry mode. For this analysis, a preliminary best estimated trajectory (BET) was provided by Intuitive Machines. The MAPS transmission mode is designed to provide a telemetry packet to any listening users that contains a complete state solution of the host vehicle (with a consistent set of time, position and velocity) as well as timestamp prior to transmission from the vehicle. During LN-1 operations, this packet was timestamped immediately prior to sending the packet to the radio for transmission. Once received, DSN stations would provide an Earth receive time (ERT) that identifies the reception time of the packet. For these test cases, comparing the two timestamps should correlate to a range measurement between the two assets. Using the BET, it is possible to provide an estimate of what this range measurement should be over the course of each pass.

To provide a time sync to the payload upon power-on, a specific command is sent to the payload. The lander essentially intercepts the command and places the time at the next pulse-per-second (PPS) tick on the lander side into the packet and holds the packet until that tick is received, at which point the command is sent to the payload. The payload overwrites its current time estimate with this new value as the total number of seconds and resets its sub-second timer. The payload continually tracks ticks per PPS for each source and can be commanded to use either of these for primary timekeeping.

Two effects were observed from the test results: the variable bias at the start of the pass and the large drift over the course of each pass. The initial bias is due to using the onboard clock, and as such the initial timing is sensitive to the onboard accuracy as well as synchronization and latency at the time command. The payload expected a fixed bias to be prevalent in each pass, and was intended to be removed via calibration that would account for initial and moving clock bias and drift. The drift is larger than expected. Over some passes the packets measured a DT that varied almost 250 seconds over an hour. When the data is fit to the truth estimate, this results in a .0217 seconds/second clock drift that was fairly repeatable across all the cruise passes.

When applying the correction of bias per pass and drift per pass, it is possible to gain more insight into the short-term stability of measurement process. These results are shown in Figure 5. In this plot, the measured DTs are much more in line with the expected, though there is still a large noise floor, on the order of .06 to .08 seconds magnitude peak to peak, still an order of magnitude greater than the expected change over the passes. The trends align with the general slope of the observation, but when zoomed in, the high frequency noise is very apparent. This noise is likely from two sources. The first is the short-term stability of the oscillator itself under flight conditions. The second is the process by which the packet was timestamped. This was applied right as the data was transmitted from the controller board to the radio via RS-422. This data was generally very small, and there is a fixed latency of transmission over the connection (though the data rate was maximized to reduce this impact).

The other transient effect is how the packet was prepared for downlink. The controller board provided a pre-packaged Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) Space Packet to the radio, which then applied additional encoding to enable data correction and operation at lower signal power levels at Earth. This was important due to the small patch antenna and limited power output of the radio (30 dBm). Before transmission, the radio processed the data using encoding into a Telemetry (TM) packet, Reed-Solomon encoding and randomization. Each packet was a fixed size with the intention to minimize the uncertainty in processing time. Lastly, when no packets were available, the radio would fill in with empty packets to ensure a constant transmission stream. These were of fixed size and would introduce additional uncertainty between the timestamp and data transmission. To negate this, the team optimized the rate of packet transmission to the radio to ensure there was always a packet in the outgoing buffer ready to go to avoid any latency. While these were intended to reduce uncertainties in radio processing, the overall noise of the clocks and short-term stability of the processing still resulted in a large noise term.

To characterize this data, the number of ticks per PPS is shown in Figure 6. The base rate of the clock was set to 10 MHz. The plots capture time since the start of the pass on the x-axis and ticks per PPS on the y-axis. The blue plot compares the onboard oscillator to the CSAC, and the red is compared to the vehicle’s PPS. The two results tend to follow each other fairly well, though a fixed offset can be seen between the two. This data was captured at a lower rate (~ Hz) so does not show the high frequency noise as seen in Figure 5. Not only is there an offset between the onboard clock and reference sources, but it does change over the pass. And this change is a different slope during cruise versus from the surface.

Prior to flight, it was known that the payload and CSAC require an extended period to thermally equilibrate. To provide insight into this behavior, the internal temperatures across the payload can be tracked over time. This is shown in Figure 7. During cruise, it can be seen that the payload was often on the cold end before being powered on. For these cases, the payload was initially warmed to low cold operational temperatures, turned on, and then commanding began. Once the radio was turned on and the power draw increased, the temperature across the payload rapidly increased. This correlates inversely to the observed ticks per PPS. As the temperature increased, the ticks also increased. This behavior was repeated over each test, providing insight into the observed time deltas. As shown, the payload never achieved thermal equilibrium, though at the longer pass, the payload’s temperature gain did begin to slow.

These results can also be corroborated with pre-flight. Figure 8 provides observations collected during compatibility testing. During this test, the payload went through similar power on temperature transients, with the temperature quickly increasing. The middle data (and highlighted in the sub-plot) shows data collected during an overnight run. In this case, the payload was left on in the EMI chamber overnight with the door closed. During this test, the temperature increased, leveled off, and once the door was closed, the temperature dropped to a stable level. Zooming in on this data, clock ticks per PPS was fairly constant over the period. The negative is due to showing the delta between the reference frequency rate (10 MHz) and the observed. This occurred over 10 hours, several hours after the pass started. The main thing to note is the fixed environment on the payload. During cruise, the payload would have had variable temperature conditions due to vehicle attitude and other disturbances. As shown, longer warm-up times would have provided increased stability of the measurements, and mirrored planned extended operations from the lunar surface (being on for several days).

Paths to a Lunar Node-2

LN-1 is a first step toward deploying surface navigation aids to support a variety of users and functions. These include providing landers with a precise well-known reference to aid in precision navigation; providing a capability to monitor and observe other in-situ navigation signals; providing a radiometric signal that can be used to “direction find” to a known location; and providing a psuedolite signal to increase coverage of robustness of signals generated by orbital assets. Multiple follow-on efforts are underway to continue to develop and mature the Lunar Node concept toward its next flight opportunity:

• Ongoing characterization to assess long-term stability as a function of temperature and clock reference.

• Implementation of a software-defined transmitter and receiver of the proposed LunaNet Augmented Forward Signal (AFS)

• Flight EDU with an AFS receiver implementation to form the basis of a LCRNS monitor station to provide an early demo and verification of the Lunar Communications Relay and Navigation System’s (LCRNS) PNT capability from the lunar surface.

• Support hardware, such as a power management system, additional control board components, power storage

• Demonstration and use of LN-1 beacon capability (one- and two-way in field demonstrations)

In addition to flight hardware upgrades, the team is also evaluating several opportunities where the payload may be used to help support surface operations. One approach is to operate as an independent instrument deployed to the lunar surface as part of a broader mission. In this scenario, one or two LN payloads would operate from the surface. These would provide cross-link signals to each other and perform reception and two-way ranging with any deployed LunaNet-compatible orbital elements. An alternate approach would be to take the same approach as LN-1 and operate as a hosted payload on a future landed asset providing power and thermal control. With a two-way capability, the payload would be supported by lander-command as well as direct form ground commands. This operational mode would perform many of the same operations as the previous demo approach but may include additional communication direct to Earth to provide more observation and direct time synchronization. This would allow for a direct comparison between timing being provided by in-situ resources and direct to high fidelity clocks on the terrestrial surface. The team continues to evaluate both approaches to guide technical implementation and testing to focus toward future potential flight opportunities.

Forward Work

Given the potential approaches and design updates needed for a future Lunar Node revision, the team continues to make progress across a variety of efforts to mature and advance its capability. At a fundamental level, this is focused on long-term ground testing and evaluation of the flight-like radio procured post compatibility testing. This radio provides upgraded capability to address challenges identified in testing, as described in [9] as well as the similar PN transmission mode. The team is developing a ground test infrastructure to enable validation of the observed results seen in-flight to better document the interaction between temperature and clock stability. As part of this study, the payload will remain on for extended periods of time to mimic the planned surface operations to provide insight into the long-term behavior of the payload using the flight spare hardware. Additionally, several advanced timing sources are under evaluation for future payloads. These also will be evaluated, providing a reference PPS (similar to the signal provided by the lander) to allow for comparison between these sources, the onboard oscillator, and the Space CSAC. For all of these scenarios, stability will be tracked over several days. While the fundamental approach to packet timestamping is limited because of the designed interface with the radio, the team will continue to assess alternate methods for providing data to the radio to reduce the uncertainty in this latency.

Lastly, the team has active procurements with vendors to provide the next level of capability. At a low level, this includes power generation, storage and distribution hardware to enable a fully autonomous payload to support future lunar surface deployed payload calls. Additionally, the team is pursuing multiple paths toward development of capabilities that are compatible with the merging LunaNet Interoperability Specification (principally, the AFS signal definition). In addition, this approach will implement a PN ranging transmission and reception modes consistent with the JPL PN code to enable stability and evaluation of the Lunar Node-1 flight spare. These will be used for field testing as well as laboratory evaluation and will accelerate the deployment of this capability both within NASA and the commercial market.

Conclusion

With the current investments being made in orbital relays, the highest priority need for hardware like Lunar Node-1 is to augment and provide additional coverage to enable real-time navigation architecture in a focused region of interest. This is particularly of need for non-South Pole focused missions, where multiple interoperable constellations are being deployed for support. These additional references can be deployed as part of the lander or other mobility systems and can use multiple approaches to provide augmentation. The payload team has taken key lessons learned to continue toward future ground and flight demonstrations, including upgrades to modern LunaNet signal specifications (AFS) and the ability for two-way time transfers to enable a higher rate time synchronization to Earth-based clocks. With these upgrades, the team continues to work toward the next iteration of Lunar Node and helping to augment and support the deployment of lunar orbital navigation constellations to enable precision time transfer and navigation across the lunar surface.

Acknowledgements

Funding provided by NASA-provided Lunar Payloads from NASA/SMD, with Ryan Stephan acting as PEO. Integration with Intuitive Machines led by the CLPS Project Scientist Office by Susan Lederer, Frank Moreno and John Gruener. Flight ground networks provided by DSN through our Mission Integration Manager, Kathleen Harmon, with extensive support by JPL and Peraton staff for testing, integration and operations. Operations conducted out of the HOSC in the LUCA lab with primary support from Sarah Watkins, Brandyn Rolling and Geoff Lochmaier. Our appreciation is due to all of the staff who keep the HOSC and operational flight networks running. LN-1 was designed, built, assembled and tested by NASA/MSFC. The flight would not have been possible without the incredible support of the electrical, mechanical and assembly shops as well as the on-site testing capabilities (EMI, Vibe, TVAC). The team is grateful to all who have supported LN-1 and previous SNS and MAPS efforts that laid the groundwork for this mission, including management and prior partners and collaborators.

This article is based on material presented in a technical paper at ION GNSS+ 2024, available at ion.org/publications/order-publications.cfm.

References

(1) Smith, Marshall, et al. (2020). “The Artemis Program: An Overview of NASA’s Activities to Return Humans to the Moon.” 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference.

(2) Hooke, A. (2001). “The interplanetary internet.” Communications of the ACM 44.9 (2001): 38-40.

(3) Israel, D. J., et al. (2020). “Lunanet: a flexible and extensible lunar exploration communications and navigation infrastructure.” 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference.

(4) Wollenhaupt, W. (1970). “Apollo orbit determination and navigation.” 8th Aerospace Sciences Meeting.

(5) Nicholson, A., et al. (2010). “NASA GSFC lunar reconnaissance orbiter (LRO) orbit estimation and prediction.” SpaceOps 2010 Conference Delivering on the Dream Hosted by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center and Organized by AIAA.

(6) Anzalone, E., et al. (2015). “Multi-Spacecraft Autonomous Positioning System: Low Earth Orbit Demo Development and Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation.” Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites. No. M15-4828.

(7) O’Dea, Andrew, et al. (2015) 214 Pseudo-Noise and Regenerative Ranging. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 810-005 214 Rev A, 2015.

(8) Wattles, J. 2024, February 28. “New images share unprecedented view of how Odysseus spacecraft landed on the moon.”Cnn.com/2024/02/28/world/odysseus-spacecraft-first-images-moon-surface-scn/index.html.

(9) Anzalone, Evan J., Jensen, Jacob, Statham, Tamara L., Bryant, Scott H., Harmon, Kathleen A., Lee, Greg, Abbod, Mike G., Barter, Randy E., Ibarra, Albert, Hoffman, Timothy J., Morgan, Lorenzo L., Overcash, Ricky D., Rokke, Collin J. (2022). “Ground-testing of One-way Ranging from a Lunar Beacon Demonstrator Payload (Lunar Node-1),” Proceedings of the 2022 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, Long Beach, California, January 2022, pp. 565-581. https://doi.org/10.33012/2022.18216.