LightSquared’s proposed GPS receiver tests are relying on an outdated standard of GPS accuracy, a choice some experts suggest is a maneuver aimed at dramatically lowering the bar the would-be wireless broadband company has to meet for showing noninterference to GPS signals.

LightSquared’s proposed GPS receiver tests are relying on an outdated standard of GPS accuracy, a choice some experts suggest is a maneuver aimed at dramatically lowering the bar the would-be wireless broadband company has to meet for showing noninterference to GPS signals.

The Air Force has long gotten plaudits for the outstanding performance and accuracy of the GPS system — year after year improving on the service levels promised in the 2008 GPS Standard Positioning Service (SPS) Performance Standard. Although that standard no longer reflects the modern service, military officials have declined to change it, sticking with an outdated yardstick as a hedge against a potentially more challenging budgetary and operational environment in the future.

LightSquared, however, is now using the 2008 document as the foundation for its GPS receiver tests. Experts agree the official SPS standard is low enough that the company may be able to argue that interference from its activities in the band next to GPS will not adversely affect its signals to the point that they don’t meet the government’s own criteria.

Since 2010 LightSquared has been trying to rezone its satellite frequencies to support a terrestrial broadband network with up to 40,000 powerful ground transmitters. Receiver tests in 2011 showed that the network’s signals would interfere with the vast majority of GPS receivers, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) tabled LightSquared’s plan in 2012. The firm filed for bankruptcy later that year.

The company is now poised to emerge from Chapter 11 and is pressing to have its proposal reconsidered. To support that ambition the company launched tests of 45 types of GPS receivers in August, including user equipment representing cellular, high precision, general location and navigation, and timing categories as well as certified and non-certified aviation receivers.

The test plan, which was filed with the FCC on August 25, will look for the impact of its proposed LTE (Long-Term Evolution) wireless signals on GPS receivers from a variety of manufacturers.

“Roberson and Associates is commencing a clear and comprehensive test of whether LTE wireless broadband in midband spectrum causes actual harm to GPS devices,” LightSquared spokeswoman Ashley Durmer told Inside GNSS.

Actual harm in these tests is to be measured by the impact on KPIs — that is, Key Performance Indicators — a measure chosen by LightSquared over the widely accepted measure of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), although SNR data will be collected. The KPI, according to a chart in the plan will largely consist of the impact of the LTE signal on GPS position accuracy but will also include timing error and loss of lock for real-time kinematic positioning.

The GPS Innovation Alliance (GPSIA) has previously deemed KPI as being “of questionable relevance.”

“Many of the performance requirements for GPS devices are internationally agreed upon by the International Telecommunications Union, the International Civil Aviation Authority, and other world standards bodies,” the organization wrote in August 14 comments on an earlier draft of the test. “GPSIA continues to maintain that a proceeding such as this, focused on one service provider, is not an appropriate place for domestic modification of established international standards that would have repercussions not just within our borders but for numerous cross-border applications, such as aviation.”

The Alliance declined to comment on the new plan, saying in response to a query from Inside GNSS that “its review of the filing was ongoing.” In earlier filings, however, the GPSIA made clear that it considered LightSquared’s tests to be redundant to the work being done on the Adjacent-Band Compatibility (ABC) Assessment by the Department of Transportation.

Durmer said that LightSquared expects the ABC Assessment test plan to appear in the Federal Register soon and that the company might file an update of their test plan at that point. She could not say how a test plan update could be integrated with results from testing already under way.

Simulating a Test, Picking the Numbers

The LightSquared tests will rely entirely on simulation rather than field tests in operational environments with real signals in space, according to the plan. Those simulations, moreover, will have errors introduced into the GPS signal based on information from the GPS Standard Positioning Service (SPS) Performance Standard.

The numbers in the outdated standard are “almost meaningless,” satellite navigation expert Logan Scott, old Inside GNSS. “The specifications, and what the satellites actually do and the way we actually use the signals, are just two completely different things.”

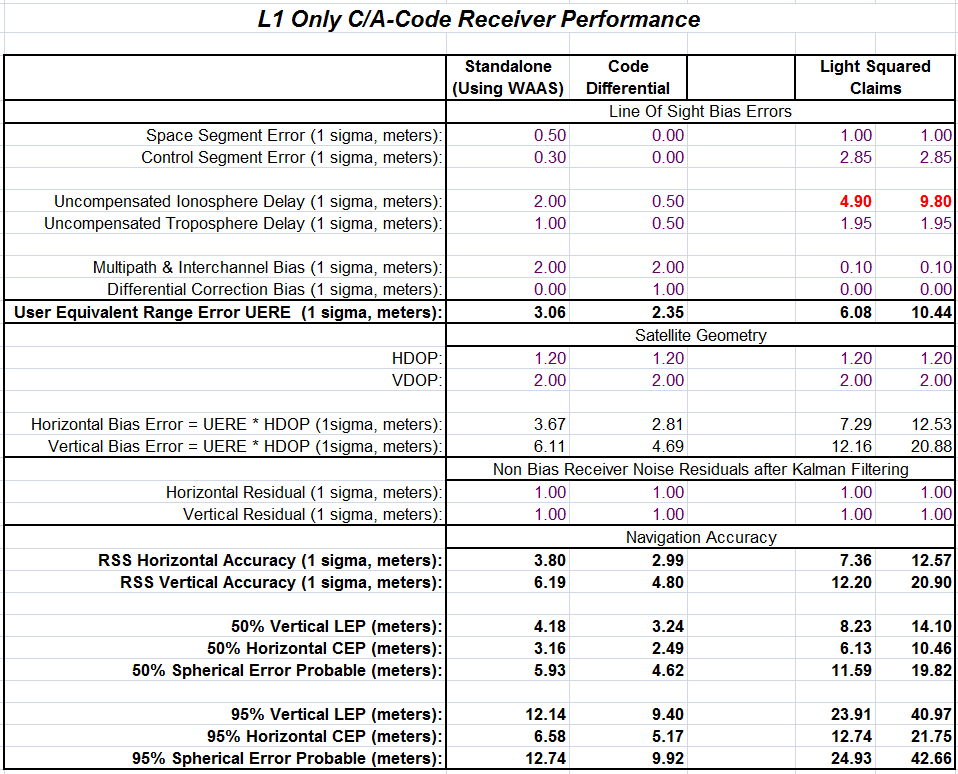

For example, said Scott, the current space segment and control segment contributions to GPS ranging errors are about 0.50 meter and 0.30 meter, respectively. The corresponding numbers derived from the SPS Standard, he said, would be 1.00 meter and 2.85 meters respectively. (Interestingly the signal-in-space, or SIS, performance calculated by Scott based on his numbers is 0.60 meter, which is close to the actual SIS performance of 0.7 meter for 2014 reported on June 15 by the now-head of the GPS Directorate Col. Steve Whitney).

The differences between the current figures for ionospheric delay and the figures in the standard are also large. Scott, who is not affiliated with LightSquared or any of the GPS receiver manufacturers, used figures based on current GPS performance and practice to calculate the user equivalent range error (UERE) for two receivers — a standalone GPS receiver using, as many now do, corrections from the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS), and a code differential receiver. He then made the same calculations based on the test plan and the SPS Performance Standard. The standalone and the code differential GPS receiver would have an on-the-ground accuracy of six and five meters, respectively; that is, a user would be within six or five meters of the actual three-dimensional position 50 percent of the time. The ionospheric delay data in the Performance Standard relied on by LightSquared would balloon that error range to 12 to 20 meters, according to Scott. (See accompanying table.)

Other issues emerge from the LightSquared test plan as well, Scott told Inside GNSS. For example, despite asserting that the plan would take into account temporal and spatial variations in signal levels, it fails to describe any propagation models.

“They never include propagation models of any sort — and that’s my point,” said Scott. “If you’re going to say that this is going to cover expected environmental effects, including temporal and spatial variations, you need to [specify the model].”

Scott also pointed out that the test plan describes in its cellular phone test description a 30-meter requirement for 2-D position error 95 percent of the time in an open-sky test.

“That is just abysmal performance,” said Scott. Current equipment would typically have accuracies of two to three meters, he said.

With the bar set so low, he noted, it would be possible to inject a lot of interference and still be able to meet the standard.

Testing to Outdated Standards

Inside GNSS asked LightSquared about the propagation model, the use of simulators for the testing and other elements of the test including the use of the 2008 Standard Positioning Service Performance Standard. The firm said it was unable to respond by press time.

LightSquared has been aware for weeks, however, that the accuracy standard it was choosing was out of date. Reed Hunt, in a July 17 interview with Inside GNSS about draft of the test, flatly declined to discuss a direct question on the matter — insisting that if the GPS companies had any doubts they should express them in writing.

“If any one of the GPS companies believes that, they have a last clear chance to send us a letter explaining their perspective,” said Hundt. “We filed this publicly so we could get comments.”

Hundt, a former FCC chairman, is now an attorney representing LightSquared. He is also set to be on the board of New LightSquared, the name the firm will have in its reconstituted form when emerges from bankruptcy.

Perhaps creating engagement around the SPS Performance Standard (commonly referred to as the SPSS) is actually the objective of the tests, experts suggested.

“What [LightSquared is] trying to say is the SPS performance specification is the governing document defining the performance of GPS receivers,” said an expert who asked not to be named because of the extreme sensitivity of the subject. “But the fact is the system performs a lot better than its specification — always has.”

The Air Force has declined to update the requirement because they don’t want to be held to a higher standard when they’re afraid they may find themselves strapped for resources in the future, explained another source.

“They’re just not willing to make a commitment that would require future funding,” said this observer. “They can provide an excellent service today but not be held accountable for that service later on when satellites may not be operating at the level that they are [now].”

Neither of the experts speaking on background is affiliated with GNSS receiver companies or LightSquared.

Should the Air Force change its mind, said one of the experts, it could update the performance standard relativity easily.

“When it comes to the SPSS, as long as their requirements for providing a service is better than the last one, they don’t have to coordinate that with anybody,” the source said. “DoD could just draw a line tomorrow and say: ‘This is our new SPSS standard.’”

If the Air Force does not update the standard, the expert suggested, they could find themselves dealing with signal issues throughout the United States.

“If the SPSS standards are not raised to current capabilities,” said the specialist, “you will be measuring the impact in a way that will allow interference to occur.”