The firefight between LightSquared and the GPS community has sparked regulatory brush fires around Washington with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Congress, a half dozen executive agencies, and numerous companies moving to address a new and likely larger battle over receiver standards, radio frequency spectrum efficiency, and RF spectrum protection.

The firefight between LightSquared and the GPS community has sparked regulatory brush fires around Washington with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Congress, a half dozen executive agencies, and numerous companies moving to address a new and likely larger battle over receiver standards, radio frequency spectrum efficiency, and RF spectrum protection.

On February 14, the FCC reversed course and moved to withdraw its January 2011 conditional waiver order allowing LightSquared to proceed with an all-terrestrial wireless broadband network in radio spectrum adjacent to GPS and other GNSS services. Extensive testing over the past year, however, demonstrated a great probability of unacceptable interference to GNSS.

Although the LightSquared/GPS mess may have triggered the discussion, the heat is coming from the economic promise of mobile broadband and the reality that mobile applications need room to grow.

Smart phones require 24 times the spectrum resources of a regular phone, and tablet computers need 120 times the resources, explained Julius Knapp, the chief of the FCC’s Office of Engineering and Technology. There are 328 million mobile phone subscribers, he told attendees at an FCC workshop on receiver standards, and 90 percent of them leave their phones on 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

When the White House announced its broadband plan in February 2011, it promised to find 500 megahertz of spectrum for those mobile users. LightSquared was widely seen as a big down payment on that promise and now the check has bounced. The workshop, held March 12 and 13 in Washington, is a step toward finding another way to make good on that pledge.

The answer, the FCC and the wireless communications industry are suggesting, is to set standards for receivers — including, in particular, GPS receivers — so that adjacent bands might be repurposed for applications that would otherwise cause interference. In contrast, GPS advocates among federal policy makers and in the receiver manufacturing sector would like to couch the debate more in terms of spectrum protection, specifically GNSS spectrum.

Multiple Approaches In its February 14 letter to the FCC concluding that the LightSquared’s interference to GPS was not solvable “within the next few months or years,” the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA, which oversees government use of frequencies) promised to take up the issue of spectrum efficiency and protection.

NTIA administrator Lawrence Strickling picked up language in a January 13 letter to NTIA from the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Executive Committee (PNT) Executive Committee (ExCom).

In their letter, the ExCom co-chairs Ashton Carter, deputy secretary of defense, and John Porcari, deputy secretary of transportation, said the committee proposed “to draft new GPS Spectrum interference standards that will help inform future proposals for non-space, commercial uses in the bands adjacent to the GPS signals and ensure that any such proposals are implemented without affecting existing and evolving uses of space-based PNT services . . ..”

Strickling modified that language and framed it in a section headed “GPS Receiver Standards.”

“This task will require striking the right balance between interference caused by transmitters and performance of GPS receivers,” he wrote. “NTIA recognizes the importance that receiver standards could play as part of a forward-looking model for spectrum management even beyond the immediate issue of GPS.

Accordingly, in parallel with our efforts with the federal agencies, NTIA urges the FCC, working with all stakeholders, to explore appropriate actions to mitigate against the impact GPS and other receivers may have to prevent the full utilization of spectrum to meet the nation’s broadband needs.”

This theme was picked up in a March 13 presentation to the plenary session of the Munich Satellite Navigation Summit, by Joel Szabat, deputy assistant secretary for transportation policy.

“We have to look at ways we can allow other uses in spectrum adjacent to GPS,” Szabat told his audience. “That is our goal over the next few years — to try to develop GPS protection standards so that other users of adjacent spectrum know what they can do and GPS manufacturers can know their limits. So that we don’t have to work on this problem on a case-by-case basis.

As the controversy evolved over prospective interference from its proposed network of terrestrial transmitters (known by the rather bureaucratic term, ancillary terrestrial components or ATCs), LightSquared began advocating the need for GPS receiver standards.

Although it appears unlikely that any change could be implemented fast enough to enable the Virginia firm to relaunch its network plans, the commission signaled its intention to explore receiver standards in its February 14 statement proposing to vacate the waiver it had granted the would-be broadband firm.

The LightSquared/GPS proceeding “revealed challenges to maximizing the opportunities of mobile broadband for our economy,” the commission wrote, and the government and industry must find a way to free up frequencies. “Part of this effort should address receiver performance to help ensure the most efficient use of all spectrum to drive our economy and best serve American consumers.”

During the workshop experts suggested several approaches to setting receiver standards (though the speakers made clear the ideas were their own, and not FCC policy proposals).

The direct approach, as described by Dennis Roberson, vice provost of the University of Illinois Institute, would be to simply set standards for receivers. Bringing both transmitters and receivers into consideration when trying to limit interference is necessary, he said, and would ease uncertainty.

“[Leaky receivers] admit undesired emissions from transmitters in adjacent bands causing the receivers interference,” said Evan Kwerel, senior economic advisor, FCC Office of Strategic Planning and Policy Analysis.

Another approach would be to require receiver performance standards, as opposed to design standards, and employ self-certification. This would enable technology-neutral rules, said Pierre de Vries, senior adjunct fellow at the Silicon Flatiron Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

This appears similar to an idea, suggested by GPS experts, which would make adoption of the standards voluntary. The example most often mentioned by GPS insiders as a model is Underwriters Laboratory. The non-profit organization tests electronic equipment to see if it meets standards set for safe operation. Devices that meet the voluntary criteria are granted a UL label — indicating their safety — a stamp of approval consumers have come to expect.

Indeed, the GPS Directorate at Los Angeles Air Force Base, which is responsible for much of the Department of Defense’s equipment development and acquisition efforts, has suggested a UL-like approach for next-generation military GPS user equipment, including a proposed “common GPS module.”

Spectrum Regulation vs. Receiver Standards

The FCC’s Kwerel suggested putting a time limit on the current practice of giving existing spectrum users indefinite protection from new users.

When a new allocation is set up in a band earmarked for the sort of high-density, power-intense uses typical of cellular applications, he suggested, those in an adjacent band would be given a certain number of years to adapt their receivers to accommodate the new neighbors. After that point they would be subject to interference.

This approach should apply to frequencies from 300 to 3,000 MHz, which includes all the current GNSS frequencies in the L-band portion of the RF spectrum, he proposed, but would not come into play unless bands were being repurposed. The period of protection would be based on an average of the normal, equipment replacement cycle.

One of the questions that would have to be settled before such an approach is implemented, Kwerel said, is whether services where receivers are not under control of licensee, such as TV or GPS, should be handled differently.

Protecting GPS Spectrum

A second approach, favored by many in the GPS community, would focus on better safeguards against neighboring frequencies being reallocated to less compatible uses, as occurred with LightSquared.

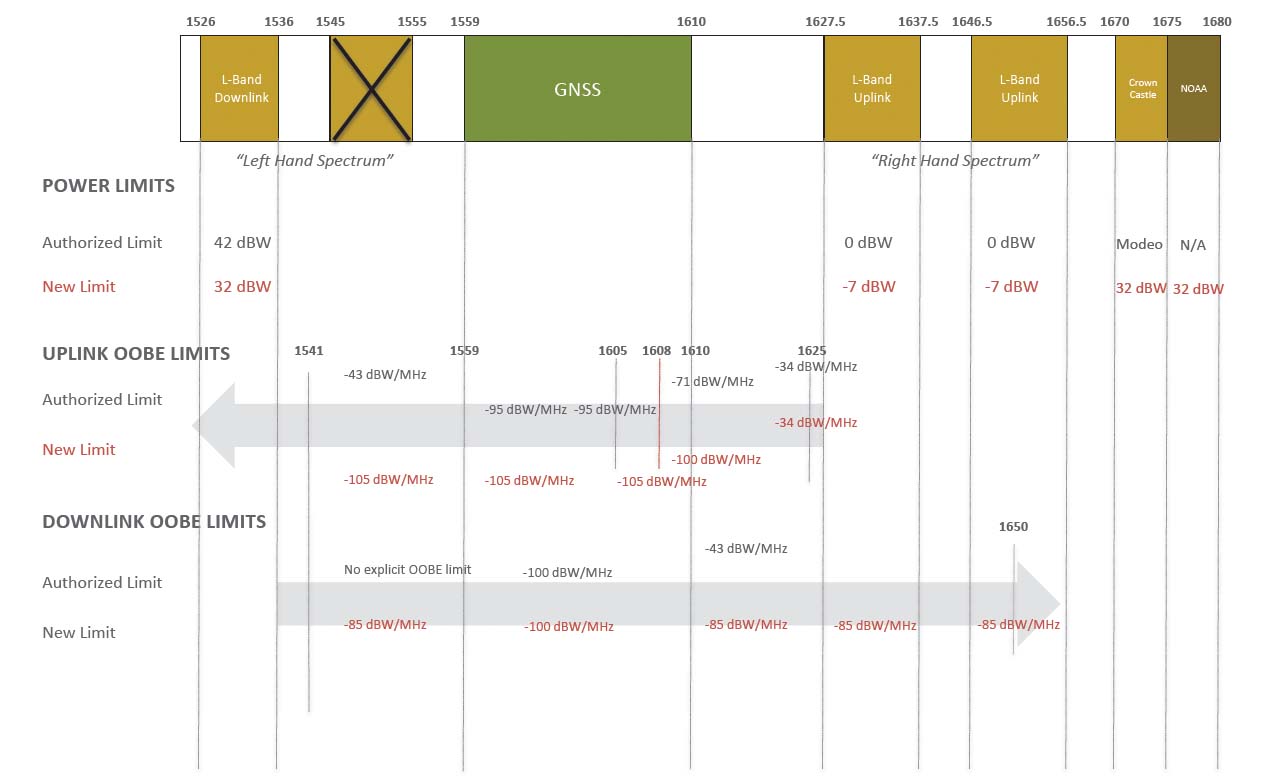

“Improved protection for GNSS spectrum might take the form of the inclusion, within domestic and international spectrum regulations, of the maximum levels of out-of-band interference that may be tolerated by the vast majority of fielded GNSS equipment without causing ‘harmful interference,’” said Christopher Hegarty, director of communication, navigation, and surveillance engineering and spectrum at The MITRE Corporation, a federally funded R&D organization that supports the Federal Aviation Administration.

“These levels should be specified as maximum field strengths for both vertical and horizontal polarizations since GNSS antenna characteristics vary considerably,” Hegarty told Inside GNSS. “Also important are the locations at which such limits should be measured. For instance, ‘power-on-the-ground’ limits, unfortunately, do not protect many of the areas where GNSS is used today, e.g., on aircraft, on each new floor during construction of high-rise buildings, within reference stations atop many rooftops, etc.”

Hegarty added, “If regulations are developed to protect GNSS, there will likely be considerable debate between the GNSS community and mobile broadband proponents on exactly how these limits are specified for obvious reasons.”

Hurting Innovation

All of the GPS experts who spoke to Inside GNSS about receivers standards were concerned that specific technical mandates could curtail creativity.

Part of the anxiety within the GPS community stems from a sense that other spectrum users, communications users in particular, do not understand how positioning data is derived from the GPS signal.

GPS devices measure to the sub-nanosecond the points at which bit transitions occur in a GNSS signal, explained John Foley, the director of aviation GNSS technology at GPS receiver manufacturer Garmin.

By analogy, if communication users only want to know whether the light in a room is on or off, navigation users want to know — with absolute exactitude — where you are in the process of flipping the switch.

Unlike communications devices that transmit and receive within narrow bands at comparatively high power from terrestrial facilities often within geographically controlled areas, GNSS signals are spread-spectrum signals transmitted from satellites with a global coverage and received at a power level that is below the background noise of the RF spectrum. High-precision GNSS receivers “de-spread” these signals by gathering up a wide swath of signal bandwidth to wring every bit of power and data out of the signal.

Foley pointed out during his FCC workshop presentation that experience has shown that mandating how devices are designed slows down the creative forces that generate new applications. He also pointed out the striking difference, he told Inside GNSS, in the speed of innovation between the consumer receiver market and the certified receivers made for aviation uses that, appropriately, must adhere to detailed design requirements and certification processes that can take years to implement.

“We at Garmin certainly are supportive of broadband,” said Scott Burgett, the company’s director of GNSS and software technology. “[But] we have to be careful how we do this so we don’t severely encumber the GPS navigation bands.”

MITRE’s Hegarty said that some useful lessons could be drawn from the experience with aviation GPS receiver standards.

“In fact,” Hegarty pointed out, “even LightSquared has provided inputs to the FCC stating that the form of the interference requirements (but not the levels) within aviation standards created by RTCA, Inc., could be used for the broader GNSS community.

Interestingly, domestic and international aviation standards were in place prior to the FCC ancillary terrestrial component (ATC) rulemaking, but do not appear to have been taken into account in the development of the technical characteristics in the FCC rules for this service. Certainly, the aviation community would expect that the 60,000 fielded, certified aviation receivers should continue to be protected by any implemented standards.”

Deciding on an approach to setting standards may not, however, be the necessary first step. It is not at all clear that the FCC actually has the power to regulate receivers. Sources familiar with the controversy said legal challenges may arise around this question should the FCC move to establish receiver rules.

“There are a variety of ways that, I think, the FCC could exercise jurisdiction — but there is no question it is controversial,” said Gregg Skall, a telecommunications attorney with the Washington law firm of Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, PLLC.

“Sec 301 of the Communications Act,” he explained, “says basically that no person may use or operate devices to transmit energy or communications signals in the United States — or when interference is caused, they can’t cause interference — and they can’t do that without FCC approval. That’s the basis on which the FCC’s jurisdiction is founded.”

Skall added, “Sec 302 says the FCC can make reasonable regulations governing the interference potential of devices which, in their operations, are capable of emitting radio frequencies, and establishing minimal performance standards.”

However, he continued, “[The Communications Act] doesn’t directly say that [the FCC] can regulate all devices that receive communications . . .. So the question is whether FCC can regulate mere reception.”

The question could be settled by the court, Skall said, or Congress could step up — as it has in the past — to expand the FCC’s mandate.

The View from The Hill

Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) chairman of Energy and Commerce’s Communications and Technology Subcommittee, which helps oversee the commission, has already expressed interest in revamping the FCC’s powers. He has also reportedly had GPS receiver standards on his to-do list.

Walden has been critical of the FCC in the past, asking questions about the power of the FCC chairman and the agency’s handling of LightSquared. He was one of three members that sent letters to the agency on February 28 demanding a long list of LightSquared-related communications and testing information from the FCC, the NTIA, and the co-chairs of the PNT ExCom.

Interestingly, the congressional letters, co-signed by Energy and Commerce Committee chairman Fred Upton (R-MI) and Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee Chairman Cliff Stearns (R-FL) also requested information on receiver standards.

The three congressmen asked the NTIA and PNT ExCom to “please describe any work” they have done or were planning to do “to ensure that GPS devices procured and used by federal agencies are appropriately constructed so that future deployment of terrestrial service in spectrum near or adjacent to the GPS bands will not impact GPS service.”

But Congress is doing more than just asking about standards. The Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 (H.R.3630), passed in February and shortly thereafter signed into law, tasked the U.S. comptroller general with conducting a study to, among other things, look at the “value of improving receiver performance as it relates to spectral efficiency.” These sorts of reports are important because they often form the basis for future legislation.

*Sources tell Inside GNSS that federal agencies are already preparing to provide the information they expect will be requested for the study, and the matter will likely be taken up by the PNT Steering Committee, which may coordinate their efforts.

New White House PNT Policy Effort?

What may also be on the PNT steering committee’s task list is a look at rewriting the current national security policy directive (NSPD) on PNT. The most recent version of this key policy document was published in December 2004 and established the current military/civil GPS management structure of the PNT ExCom, and confirmed that GPS would continue to be provided worldwide free of charge. The 2004 NSPD set the goals of keeping GPS “the pre-eminent military space-based positioning, navigation, and timing service” and providing “civil services that exceed or are competitive with foreign civil space-based positioning, navigation, and timing services and augmentation systems.”

Sources familiar with the issue tell Inside GNSS that an update of the NSPD by the White House would be about more than spectrum issues — though one knowledgeable source said the problems unveiled by the LightSquared fight would be taken into account. Any rewrite might also look, for example, at the role of the GPS system in a world with a burgeoning number of other navigation constellations.

Though the PNT Executive Committee will likely be asked to help gather information as a first step to any rewrite, it is not clear that the White House will actually update the policy this year. Not everyone believes that a wholesale policy overhaul is necessary.

The LightSquared issue could have been handled within the current framework, a source familiar with the issue pointed out, and there are other space-related matters that are also urgent.

While the White House national security staff is nearly done updating the nation’s policy towards launch vehicles and facilities, it has also identified remote sensing policy as an area ripe for review and possible updating.

So, although the LightSquared controversy appears, at least for the moment, to have tipped in favor of the GPS community, it also underscored weaknesses in the current structure. For example, there appears to be no reserve of money for testing when issues arise — a problem that has existed for years.

And, while the community ultimately pulled together admirably to confront the threat of interference from LightSquared transmitters, that cooperation was not assured during the early days of the controversy. It certainly would have been a good thing if someone had seen the LightSquared issue coming earlier.

During his report to the November meeting of the PNT ExCom Advisory Board, member Dr. Robert J. Hermann — a partner in Global Technology Partners, LLC with 20 years of experience with the National Security Agency — said efforts to assess the way ahead for the National PNT Architecture Implementation Plan, were hampered by the fact that the discussion did not appear connected to anyone who might actually be charged with implementing the results of the discussion. This is no way to run a railroad, he quipped.

The ExCom is perhaps a body of well-meaning and competent people, he said, as summarized in the meetings minutes, but it is not the government structure to actually make hard choices and to know what the trade-offs are.

That may be the real lesson from the LightSquared mess. Despite lessons from earlier battles over out-of-band interference, years of progress, more money, good intentions and a great deal of hard work by very competent people, the GPS community could have lost a fight where everything was truly on the line. Now an even larger battle is looming over receiver standards.

A basic rule of war is being violated, PNT Advisory Board Co-chair Dr. Brad Parkinson told the ExCom during the prolonged controversy: For GPS, there is no unity of command.