Russian Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Ivanov’s criticism of Roscosmos and GLONASS continues to ripple in news columns around the world.

Widely reported in Russian media and picked up and amplified in derivative reports, Ivanov’s complaints focused on GLONASS’s relative inaccuracy, limited coverage, and lack of user equipment.

However, aside from the fact that the person making the remarks was Ivanov — a powerful figure once thought to be in line to succeed Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, none of this is really news. Rather, it seems like another example of the phenomenon that, when people learn of something for the first time, they assume it has just happened.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Ivanov’s criticism of Roscosmos and GLONASS continues to ripple in news columns around the world.

Widely reported in Russian media and picked up and amplified in derivative reports, Ivanov’s complaints focused on GLONASS’s relative inaccuracy, limited coverage, and lack of user equipment.

However, aside from the fact that the person making the remarks was Ivanov — a powerful figure once thought to be in line to succeed Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, none of this is really news. Rather, it seems like another example of the phenomenon that, when people learn of something for the first time, they assume it has just happened.

Indeed, the most interesting commentary on the recent hullabaloo may be the suggestion by Eurasia Daily Monitor columnist Pavel Feigenhauer that insufficient progress in the GLONASS modernization program led to Ivanov’s being passed over by Putin, who named the much less visible Dimitry Medvedev as his preferred successor. Hence, Ivanov’s discontent with the system. (Of course, one can argue that Putin’s apparent desire to continue as the effective leader of Russia from a strengthened prime minister’s office in the legislative Duma might have provided sufficient reason for him to prefer a less forceful personality as president.)

In fact, GLONASS is controlled and operated by the Russian Space Forces under the direction of the Ministry of Defense (MoD), which Ivanov formerly headed, from a secured military facility in the Moscow suburb of Korolev (renamed from Kaliningrad in 1996 in honor of the chief designer of Sputnik).

The GLONASS operations facility — the equivalent of the GPS master control station at Shriever Air Force Base, Colorado — lies a short distance away from the civilian Roscosmos mission control center at which Russian operations in support of the International Space Station take place and that corresponds to NASA Houston space center.

Some years ago, responsibility for the program was nominally turned over to Roscosmos, with funding coming from both MoD and space agency budgets. But to lay the burden for the system’s performance solely on the federal space agency is somewhat akin to blaming the U.S. Department of Transportation for schedule slips in GPS modernization.

Performance Long Sub-Par

In any case, the fact that GLONASS’s performance is worse than GPS is not a recent development. It always has been, and in recent years Russian GNSS experts have been forthright in detailing the shortcomings. (See, for instance, the overview article on GLONASS in the first issue of Inside GNSS.)

The poorer performance is the culmination of a variety of factors: poorer on-board atomic clocks, less stability and predictability in the satellite orbits (and therefore less accuracy in GLONASS broadcast ephemerides), fewer satellites providing signals, an operational control and ground monitoring segment limited to Russian territory, “biases” in the transmissions from multiple frequencies that require more complicated receiver designs to calibrate accurately, and so forth.

The GLONASS modernization program is designed to overcome these limitations with improved atomic frequency standards, upgraded design of space and ground segments, and other improvements. Meanwhile, Russia is participating actively in the UN-backed International Committee on GNSS (ICG), negotiating GLONASS cooperation agreements with countries including India, and holding bilateral talks with the United States and Europe on system compatibility and interoperability.

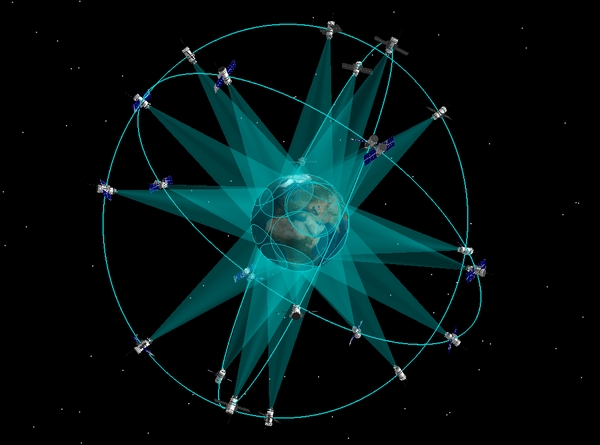

As for lack of coverage, that is a direct function of the number of spacecraft in orbit — now numbering 16, up from a low point of seven operational satellites in 2001. Under the schedule for rebuilding and modernizing the GLONASS system, which has drawn Putin’s strong backing for more than five years, GLONASS would still not reach its full complement of satellites (24) until 2009.

Russia’s published goal for matching GPS performance is even further out — 2011, when officials hope to see the constellation containing a sufficient number of modernized satellites — the GLONASS-M spacecraft now being launched and the GLONASS-K generation scheduled to appear next year.

Regarding the availability of user equipment or chipsets with which to make them, GLONASS does not lack for receiver manufacturers — several with operations in Russia — or silicon. Commercial GLONASS-capable receivers have been available since the early 1990s, and today at least a half-dozen well-known, but non-Russian, GNSS companies offer GPS-GLONASS receivers.

More properly characterized, what is probably bothering Russia’s leaders is the absence of affordable, domestic Russian-manufactured equipment — especially for mass-produced consumer applications and markets. (That’s why Nokia’s recently expressed interest in building mobile phones that can use GLONASS is particularly significant.)

As recently as a few years ago, Russian officials acknowledged that fewer than 10,000 GLONASS receivers had been produced in the country, mostly for military aircraft and vehicles.

Several organizations, including a recently privatized spin-off of the Russian Institute for Space Device Engineering (RISDE) and the St. Petersburg–based Russian Institute for Radionavigation and Time (RIRT), are designing GLONASS chipsets and OEM receivers. But such efforts have a lot of catching up to do. Late last year RISDE introduced a combined GLONASS/GPS receiver, the Glospace SK-70.

Managing the Milestones

The primary criterion of the modernization program that GLONASS failed to meet thus far is having 18 satellites on orbit by the beginning of 2008. And even that should not have come as a surprise, either inside or outside Russia, being a function of the operational life expectancy of GLONASS satellites.

Although Russia added six GLONASS-M satellites to the constellation during 2007 as planned, it was forced to decommission five satellites since the beginning of this year.

Operators of the GLONASS constellation probably hoped that they could get a little more life out of a couple of the space vehicles (SVs) and meet the 18-satellite modernization milestone. But four of the recently decommissioned spacecraft, launched between 2001 and 2003, were beyond their three-year design life and had been performing poorly for some time. Only GLONASS SV number 798, launched in December 2005, could be said to have failed prematurely.

The 2008 launch schedule would add six GLONASS spacecraft in two triple launches in September and December, if successful. With further launches planned in 2009, that would seem to give the system’s operators a chance at restoring a 24-satellite constellation by the end of next year.

Another milestone that Russia appears not to have met, however, is a decision by the end of last year on whether to add a code division multiple access (CDMA) signal to the frequency division multiple access (FDMA) GLONASS system. GLONASS CDMA signals, similar to those used by all other GNSS systems, have been proposed for the L1 and L5 frequencies. Support for the CDMA plan comes from civil and commercial interests inside and outside Russia. However, defense officials reportedly are less eager to adopt that approach, in part because a unique and widespread GNSS spectra is probably harder for adversaries to jam.