Cheryl Gramling knew early on what she wanted to do in life. Today, she is assistant chief for technology, mission engineering and systems analysis division, at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and she’s playing a key role in getting us back to the Moon.

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong took his one small step onto the surface of the Moon, and with that step, and with his moving words, he was assured a place in history. An estimated 650 million people around the world watched the event live, in homes, in auditoriums and in schoolrooms. It was a towering achievement for the men who stood on the lunar surface, but the lives of many others would also be changed forever.

Cheryl Gramling was a little girl in 1969. On that historic day in July, she was watching television while on vacation with her family in Atlantic City. “I was 8 years old at the time of the Apollo 11 landing,” Gramling told Inside GNSS. “Perhaps it sounds a bit cliché, but it was the Apollo missions that led me to my career. Watching the news broadcasts, particularly Jules Bergman with the Apollo trajectory drawn on the screen, inspired me. I wanted to design those trajectories.”

It was a profound desire that stuck with young Gramling. As a child, she liked going to summer camp, swimming, and playing tennis, but in school, her favorite subjects were math and physics. “When I was 14 years old,” Gramling said, “a friend of the family explained to me that to design those Apollo trajectories meant I needed to be an aerospace engineer. At the time, I thought engineers were just the fellows who drove trains. I had a lot to learn. But that is what led me to aerospace engineering.”

Gramling was the first in her immediate family to go to college. Her mother, who was s born in England, came to the USA in 1957 and found work as a secretary. Her father, from Baltimore, was an accountant.

First Stage

Gramling attended the University of Maryland at College Park, not far from the nation’s capital, where, aside from her classes, she enjoyed hiking and ice skating. She continued playing tennis and came to appreciate literature. She studied hard and was awarded a bachelor’s degree in Aerospace Engineering in 1983. By 1985, she was doing what she’d dreamed of, designing flight trajectories for NASA.

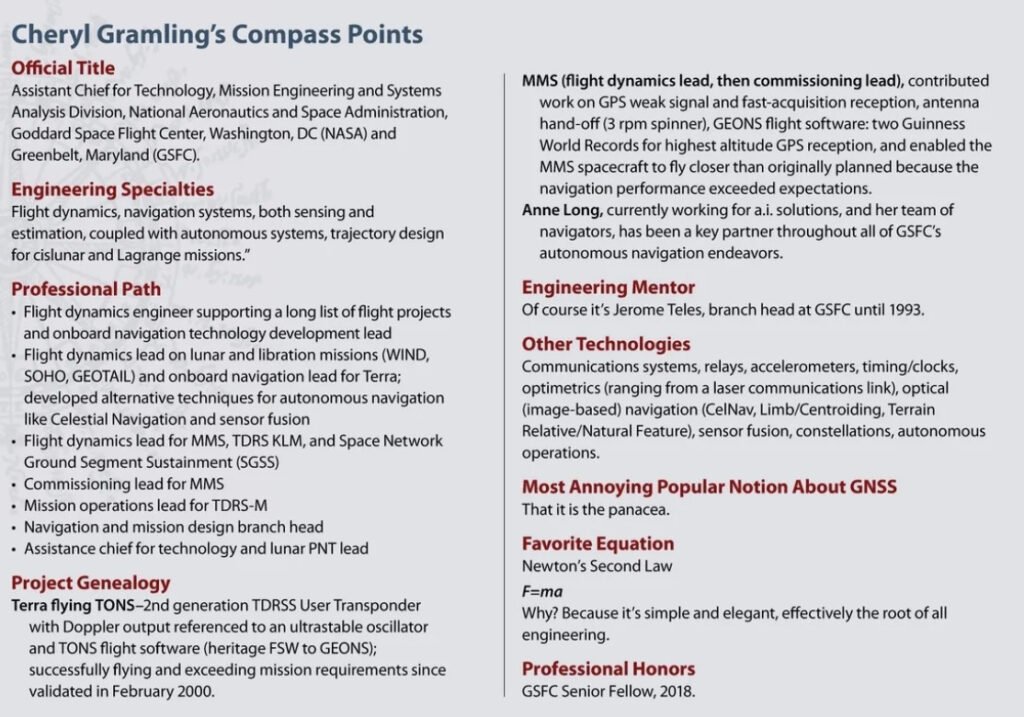

Gramling served as flight dynamics lead for WIND, POLAR and GEOTAIL at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) from June 1985 to November 1991. She designed trajectories for the WIND and GEOTAIL missions, a series of double lunar swingbys, and the highly elliptical POLAR mission, also analyzing navigation strategies for WIND and POLAR. These were collaborative projects involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS) of Japan. They entailed coordinated, simultaneous investigations of the Sun-Earth space environment over an extended period of time.

It was during her early years at NASA that Gramling first came to grips with GNSS. “In 1986,” she said, “working for NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, I was developing systems for onboard autonomous navigation using signals from NASA tracking, telemetry, and command networks, mostly the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System [TDRSS].”

That GNSS Thing

Gramling said, “I was working with the Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer [EUVE] project to fly an ultrastable oscillator and additional hardware in the flight transponder to extract the Doppler from a TDRSS forward link, then process through an Extended Kalman Filter to obtain a navigation solution for the spacecraft.” The system was called the TDRSS Onboard Navigation System (TONS). “The Project Manager, Frank Cepollina, thought it would be awesome to have a ‘Fly-Off’ between TONS and a GPS system,” Gramling said. EUVE was also flying an engineering prototype GPS receiver from Motorola.

The TONS demonstration was very successful and resulted in an operational flight system on the Terra spacecraft, which was launched in December 1999. “The solution from the GPS pseudorange data was compared offline to the TONS solution and the calibrated standard GPS solution was found to be comparable to TONS,” Gramling said. “The distinction in the era after EUVE was that TONS didn’t require separate hardware for the solution—it was part of the comm system, whereas GPS required a separate antenna, RF front end and receiver.”

Gramling remembers this as a pivotal moment, a turning point in her own trajectory. “The advantage of an instantaneous realization of your orbital position from the kinematic GPS solution was evident in the EUVE demonstration,” she said. “Once the community realized that spacecraft needed to estimate the position and the velocity, I think it changed the game in receiver processing, leading to more filtered estimates to solve for the full state.”

The GNSS deal was sealed when, in the early 2000s, Gramling worked on the Magnetospheric MultiScale Mission (MMS). “Our team was analyzing different navigation solutions for the formation of four spacecraft in a tetrahedron with varying interspacecraft distances.” MMS are 3rpm ‘spinners’ in highly elliptical orbits: phase 1 orbit was 1.2x12RE, where RE is one Earth radius, and phase 2 was 1.2 x 25RE. “Both apoapses [orbital high points] were far above the GPS constellation,” Gramling said. “The team at GSFC had been working on both fast-acquisition and weak signal reception techniques for GPS receivers, and navigation simulations showed that use of GPS could provide very accurate navigation solutions for MMS.”

Flying autonomous navigation was not yet widely accepted, but the MMS navigation team made the case to fly GPS and the Goddard Enhanced Onboard Navigation System (GEONS) flight software onboard MMS. “Our case was based on the success of TONS onboard Terra and other LEO missions flying GPS receivers, a planned inflight use of the new receiver design in a LEO environment to qualify it and calibrate it, and analysis that clearly indicated use of GPS for MMS was a mission enabler,” Gramling said.

All of this set the stage quite handsomely for her current work, developing systems for cislunar PNT, both orbital and lunar surface-based. NASA has set the ambitious goal of establishing a sustainable human presence on the Moon. A diverse set of commercial and international partners are currently engaged in this effort, aiming to set in motion a new round of scientific discovery, lunar resource use and economic development on both the Earth and at the Moon. Further, NASA believes lunar development can serve as a critical proving ground for deeper exploration into the solar system. Certainly, space communications and navigation infrastructure will play an integral part in realizing these goals.

NASA’s Lunar Communications Relay and Navigation System is part of an international architecture known as LunaNet, a services network that will enable lunar operations. This encompasses a wide variety of topology implementations, including surface and orbiting provider nodes. Four LunaNet service types are defined: networking services, position, navigation and timing services, detection services and science utilization services. “Lunar Relays will provide the Lunar Augmented Navigation System in the LunaNet framework,” Gramling said, “stemming from the terrestrial GNSS and the TDRSS to deliver a broadcast PNT service capable of providing common and mission-unique data to the lunar environment.”

Finding Love and Starting a Family

As if Gramling’s rise within NASA wasn’t stimulating enough, she managed to find another key source of interest, in the form of her husband. “We met while working at GSFC, although we didn’t work together at the time,” she said. “He is an engineer by education and is currently a program manager at NASA headquarters.”

When the couple started their family, Gramling cut back on her hours but still stayed involved. “My husband and I have three children,” Gramling said. “I was lucky enough to have a boss who supported my husband and my decision for me to work part-time while raising our children. This was before the days of official telework options.”

Gramling’s boss at the time, Jerry Teles, allowed her to work at home and was instrumental in piloting a telework program at NASA/GSFC. “Jerry was my first supervisor, as branch head, and he did not deprecate the importance or relevance of my work assignments,” Gramling said. “Working part time through the mid-years of my career was instrumental in enabling me to stay involved, continue to contribute meaningfully to missions, and then seamlessly return to full time work in 2005.”

Teles was a fierce defender against misogynistic attitudes in the workplace in the 1980s, Gramling said. “He held the bar high and expected his employees to take responsibility and to learn. After the Challenger accident, when the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory launch was delayed, Jerry developed and executed a plan to ensure all his recent early career hires, including me, received on-the-job training in relevant flight dynamics analyses to prepare this junior team for the mission.”

When Gramling showed an interest in advanced trajectory design, Teles introduced her to Dr. Robert Farquhar, under whom she learned multi-body trajectory design for lunar and Sun-Earth Lagrange missions. “Jerry also encouraged me, and others, to lead teams and take responsibility, supported by his mentorship,” Gramling said.

A Well-Rounded Life

Gramling’s three children now range in age from 30 to 25. “Our older son was a liberal arts major, and our daughter and youngest son both majored in engineering,” she said. “Outside of work, I like to bake, garden, hike, bike, walk, do needlework, read, and travel.” A quick glance at her family photos confirms Gramling indeed loves to travel, and she shares that passion with her family.

So, after a nice holiday, it’s back to the grind for Gramling, which may not be such a grind after all: “I have one of the coolest jobs in the world,” she confesses. “Working for NASA is an honor. Working on advancing technology and on navigation and guidance systems to ensure success for complex missions in challenging environments makes you want to go to work every day.”

Like so many top-flight engineers of her generation, Gramling was deeply inspired by NASA’s stunning accomplishment of landing men on the Moon. Within what seemed like just a few short years, she was working for the organization that had put them there. And there, at the Goddard Space Flight Center, she’s still doing her thing. And we can be sure she’s not just sitting at a desk with stars in her eyes. Gramling is not a dreamer, but a real moving force at NASA, as that esteemed and admired institution pushes forward on its return to the moon.