A new report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlines how, after decades of debate, the Department of Defense (DoD) system for buying and integrating space systems remains complex and fractured — causing delays, cost overruns, and cancellations among the department’s many space programs, including GPS.

A new report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlines how, after decades of debate, the Department of Defense (DoD) system for buying and integrating space systems remains complex and fractured — causing delays, cost overruns, and cancellations among the department’s many space programs, including GPS.

The requirements, budgeting and acquisition processes "are largely stove-piped in practice for DoD," wrote GAO, "resulting in most investment decisions being made on a piecemeal basis and limiting its opportunities to better leverage its resources and adjust to strategic changes."

Moreover, some 60 stakeholder organizations, both within the Pentagon and outside DoD, have a role in or influence on the acquisition process. These stakeholders include the White House as well as the intelligence agencies plus civilian agencies familiar to the satellite navigation community, such as NASA and the departments of transportation and commerce.

Of these dozens of groups, GAO wrote, eight organizations, including the Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) and the NRO (the National Reconnaissance Office), "have space acquisition management responsibilities; eleven have oversight responsibilities; and six are involved in setting requirements for defense space programs."

Because of the cost of building and launching space systems the stakes are particularly high. GAO pointed to GPS as an example, noting that it was costing the Air Force more than $500 million each for eight GPS III satellites, close to $4 billion for the next generation operational control system (OCX), and $1.64 billion for designing the first increment of terminal cards for modernized military GPS user equipment (MGUE).

"Consequently," they said, "it can be difficult to get buy-in to recapitalize large systems."

The complexity is a long-identified problem. The watchdog agency noted that in 2012 it had reported that fragmented leadership contributed to a 10-year gap between the delivery of GPS satellites and user equipment.

GAO also pointed out satellite cost overruns in their March 21, 2012, report Space Acquisitions: DOD Faces Challenges in Fully Realizing Benefits of Satellite Acquisition Improvements. The cost of the GPS IIF program, as of April 2011 they said, had jumped to $2.6 billion, "more than triple the original cost estimate of $729 million."

This latest GAO study was requested by the Senate Armed Services Committee as part of its deliberations on the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016, S. 1376. In Senate Report 114-49, a provision requested GAO to review the effectiveness of the current DOD space acquisition and oversight model and to evaluate what changes, if any, could be considered to improve the governance of space system acquisitions and operations.

A Legacy of Problems

"This has been an issue that has plagued defense space programs for decades," said Todd Harrison, director of defense budget analysis and a senior fellow in the International Security Program at CSIS. "It was pointed out even in the 2001 space commission report that Donald Rumsfeld led just before he became Secretary [of Defense]."

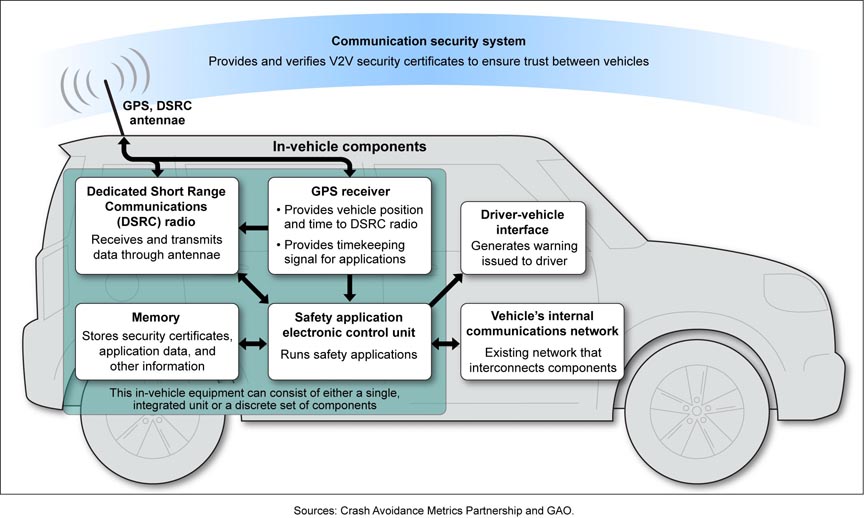

"The basic problem," said Harrison, "is that for military space systems to work there are multiple segments that all need to be developed and fielded at nearly the same time," but the program authority, acquisition, and budget authority are divided among different organizations and different military services.

"It’s not just the satellites," he said, "it’s also the ground control center and the user terminals — they all need to be developed and deployed in the same timeframe."

A good example, said Harrison, is what happened with the Mobile User Objective System or MUOS, a narrowband tactical communications satellite system. The Navy was in charge of buying the satellite and the ground control stations, but the user terminals were primarily being bought by the Army. In a situation echoing the GPS III/OCX/MGUE dilemma, MUOS has new capabilities on it that can only be utilized by new terminals that have the proper waveform, but the Army de-prioritized development of radios with the right waveform to use MUOS signals.

"The Army’s budget is totally separate from the Navy’s; so, the Army could do that,” Harrison said. “You end up launching satellites that can’t be fully utilized because another part of the system, the ground users’ (equipment), have not been developed in time."

Despite what happened with MUOS, and the GPS program’s experience with bringing military user equipment and modernized space system capabilities along together, the answer may not be to have one department in charge of all space systems, ground infrastructure, and user equipment, said Harrison.

"There’s not an easy solution to this," he said. “You can’t have the Air Force put in a position of determining what Army GPS receivers are going to get upgraded and when. You’re certainly not going to have the Air Force paying to upgrade the Army systems, especially all the integration work that goes with that."

New Role: Space Advisor

To help address these problems, particularly in light of the increasing challenges the United States faces from space-capable adversaries, the secretary of the Air Force, who was the DoD Executive Agent (EA) for Space, was re-designated as the Department of Defense’s DoD Space Advisor (PDSA).

The PDSA reviews the budget of "every entity with responsibilities for space capability development" assessing their compliance with DoD policy and implementation plans, making prioritized recommendations. The person with the day-to-day PDSA responsibilities is Winston Beauchamp, who is also the Air Force’s deputy under secretary for space.

The new position was only created in October, and the GAO agreed with the Air Force that it was "too early to gauge whether the PDSA has sufficient authority to consolidate space leadership responsibilities."

One of the key issues is that the PDSA does not have the budget clout to actually cut off funding, said Harrison. "They have influence, they can recommend that to other organizations."

Beauchamp, however, is also the Air Force’s deputy under secretary for space. "In his Air Force acquisition role," said Harrison, "there he actually could cut off funds."

Even so, Harrison pointed out, that financial authority only applies to Air Force acquisition programs. "So if there’s something going on with the Navy space program like MUOS, the PDSA would have oversight — he could recommend and try to influence what the Navy does — but ultimately the Navy controls the budget."

It’s the same kind of problem that could emerge as DoD works to upgrade GPS receivers across the entire defense enterprise to use the capabilities of the new GPS III satellites.

"You can’t make them integrate [the modernized chipsets] into their GPS receivers and their platforms," said Harrison. "So ultimately the power is about budget authority — and whoever controls the budget ultimately has the power."