Federal aviation officials appear to be moving quickly to defuse mounting pressure for the commercial use of unmanned aircraft, clarifying their authority over such aircraft and starting the public process for licensing small firms for limited operations.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has taken a tough stance in its interpretation of the legal uses for model aircraft published on June 23 in the Federal Register. The issue surged into the national spotlight when the agency failed to win a legal challenge over its authority to regulate such devices.

Federal aviation officials appear to be moving quickly to defuse mounting pressure for the commercial use of unmanned aircraft, clarifying their authority over such aircraft and starting the public process for licensing small firms for limited operations.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has taken a tough stance in its interpretation of the legal uses for model aircraft published on June 23 in the Federal Register. The issue surged into the national spotlight when the agency failed to win a legal challenge over its authority to regulate such devices.

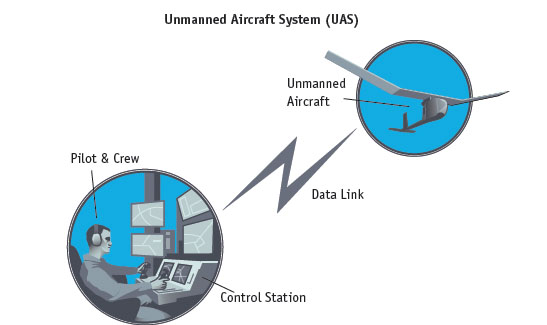

The agency had tried to issue a $10,000 fine to Ralph Pirker who, it said, had been illegally flying an unmanned aircraft system (UAS) for commercial reasons. Pirker’s lawyer asserted the device in question was a model aircraft and was therefore unregulated at the time of the incident. A National Transportation Safety Board administrative law judge sided with Pirker, to the delight of many would-be UAS operators who initially thought the case might throw open the doors for commercial flights of unmanned aircraft, more commonly called drones.

They were mistaken.

The FAA appealed the case, staying any changes. Congress also had already clarified the rules for model aircraft in the 2012 FAA Reauthorization Act — removing any wiggle room for those hoping to offer high-flying photo services, UAS-based crop evaluations, or the winged delivery of beer and other necessaries. The FAA’s formal interpretation of the rules now can be found under Docket No. FAA-2014-0396 at <www.regulations.gov> or at this link.

Although the public is invited to comment (the deadline is July 23), don’t expect a lot of changes, Mark Bury, a lawyer in the FAA Chief Counsel’s office told a June 26 symposium on unmanned aircraft sponsored by the law firm of McKenna, Long & Aldridge.

“We’ve laid down our interpretation of the statute,” said Bury, who is a lead attorney on UAS matters in the FAA. “That is our interpretation that we’re going to apply moving forward. So we’re looking for comments to see if there are any ways that we need to modify that interpretation, to address unintended consequences, for example. But that interpretation, we don’t expect it to change very much, if at all, from what is published in the Federal Register.”

The agency made clear, he said, that provisions for model aircraft are not a cover for small UAS operations.

“You can’t call your small UAS a model aircraft,” said Bury, “and say ‘I am operating for hobby or recreational purposes’ and expect that what is, in all other respects, a commercial operation will be something you get away with. You will not.”

Help from Hollywood

Anxious entrepreneurs will likely find more hope in another FAA notice published just three days later. The FAA is asking for comment on a petition to allow the firm Astraeus Aerial to operate UASs to help film movies.

The documentation describing the request makes clear operations would be on closed sets with rotorcraft weighing less than 55 pounds for flights of 30 minutes or less. It would all be done within the line of sight of the operator and at altitudes of no more than 400 feet — limits which largely follow the guidelines the FAA has been discussing for its proposed rule for all small UAS commercial operations. That rule is expected to be released late this year.

Astraeus Aerial suggests that using unmanned aircraft for filming would not only be as safe as current operations but, in fact, safer because the small craft would likely replace conventional aircraft including helicopters which could cause more damage if there was an accident.

What is particularly interesting about the application is that it is the first of seven virtually identical requests. Advisor John McGraw of John McGraw aerospace consulting helped the seven aerial filming companies devise a common manual of operations (which is considered proprietary and is not available to the public) and application language. Once the first one is approved the rest are expected to quickly follow.

And that approval could come soon. The application was only filed about six weeks ago. Even run-of-the-mill exemptions can take longer than that to get in the Federal Register, noted McGraw, who previously served as deputy director of the FAA’s Flight Standards Service.

“It’s a 20-day comment period,” McGraw told the symposium audience. “Typically in the FAA it’s 120 days to get an exemption out; usually they do better than that, although I’ve seen some languish for years and years — hopefully that won’t be the case here.”

Congress has done at least part of the work, he said, having already established that approving limited UAS operations would be in the public interest.

“I am hoping (approval) will be a matter of a few months,” he said.

The application, which can be found under Docket number FAA-2014-0352 at <http://www.regulations.gov>, has garnered half a dozen comments that are mostly supportive of granting the exemption. The deadline for comments is July 16.

With half a dozen industries expressing interest, more applications can be expected to follow in short order — the shorter the better, suggested Mark Dombroff, a partner at McKenna, Long & Aldridge. It’s a wide open process, he said, and those who file earliest will effectively craft the regulatory landscape with which those who follow will have to contend.

Firms in precision agriculture, aerial surveying, and pipeline inspection are said to be already working on applications. McGraw told Inside GNSS he is talking with firms interested in surveying tall structures like smokestacks or flare stacks. The mining industry is stepping up, he said, because pit mine operators can use UASs to survey how much material has removed better than they can any other way.

Surveyors of another kind, those tracking the fortunes of wildlife, are talking about getting seeking exemptions because UASs give them a view into otherwise inaccessible areas. For example, McGraw said, “You can get an image of how many eagles are in the nest with a very quiet aircraft from a reasonable distance without interfering with the wildlife.”

The real estate industry, whose members’ use of UASs to shoot pictures of listed properties has been widely reported, is also in conversations with McGraw about getting official approvals from the FAA.

“Obviously a lot of realtors are already using these, he said, “They’d be much better off in a legal environment.”