Congress is moving to limit the sharing of geolocation information.

The Online Communications and Geolocation Protection Act (HR 983), introduced on March 6, addresses a privacy loophole created by services like Gmail and social networking sites. Though law enforcement must get a warrant to access an archive of e-mail stored on your computer, the same protections do not exist for information voluntarily given to a third party.

Congress is moving to limit the sharing of geolocation information.

The Online Communications and Geolocation Protection Act (HR 983), introduced on March 6, addresses a privacy loophole created by services like Gmail and social networking sites. Though law enforcement must get a warrant to access an archive of e-mail stored on your computer, the same protections do not exist for information voluntarily given to a third party.

The theory had been that, if you’ve given information to someone else to hold, then it’s not private — and therefore not protected.

"When current law affords more protections for a letter in a filing cabinet than an email on a server, it’s clear our policies are outdated,” said co-sponsor Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-Wash.

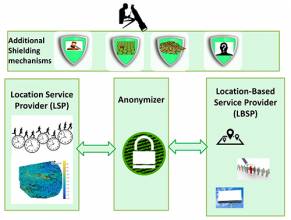

The bill would require government agents to have a warrant to access information held by third parties. It also specifically prohibits the interception, use, or disclosure of location information without a warrant or the express permission of the person involved — except in certain emergencies. Interestingly, it also prohibits those who hold such information from giving it out.

The Senate is also expected to take up location privacy legislation. A staffer confirmed to Inside GNSS that Sen. Al Franken, D-Minnesota, plans to reintroduce the Location Privacy Act (LPA) before the end of the year. The bill, as amended, last session sought to protect cell phone users from having their locations revealed by apps on their phone without their express permission. It would also act against those using location software and information for stalking purposes.

The groundwork already has been laid for the LPA, which was approved with bipartisan support last year by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Some changes in the bill’s language are likely, however, as a number of those who spoke in favor of the legislation just before the committee approved it also said they hoped to work with Franken to address some concerns.

Most of the changes mentioned seemed to be aimed at allaying the concerns of businesses that want location information for commercial purposes or were anxious about the effect of having to ask customers for permission to use that information.

The 2012 version of the LPA had allowances for law enforcement officers to obtain information “pursuant to any lawful authority or activity.” The options under such authority, however, just got smaller.

On March 5, in a ruling that could encompass geolocation information, Federal District Court Judge Susan Illston in San Francisco ruled that national security letters violate the U.S. Constitution. Federal officials have been using such letters to obtain information about customers from telecommunications companies and service providers like Google without going before a judge. Federal officials also have been able to order those served the letters not to talk about them.

“In today’s ruling the court held that the gag order provisions of the statute violate the First Amendment and that the review procedures violate separation of powers,” said the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EEF) in a statement. “Because those provisions were not separable from the rest of the statute, the court declared the entire statute unconstitutional.”

EFF had helped an unnamed firm challenge the use of the letters.

On a related issue, some 30 states are considering legislation limiting operation of unmanned aerial systems (UASs) or use of information obtained by law enforcement agencies through UAS surveillance.

Although all of the bills appear to be centered around Fourth Amendment–based privacy considerations, they are taking disparate approaches, said Rich Williams, a policy specialist with the Criminal Justice Program at the National Council of State Legislatures.

“A lot of [the state bills} address procedures for law enforcement to obtain a warrant — what should be in the scope of that as they do it,” said Williams, “There are some (bills) that just have a ban to provide for more study — a certain number of years. Other ones have requirements that (UASs) be in compliance with the FAA, some require that there not ever be a weapon mounted to them. Some require that you can’t use facial recognition or biometric technology attached to them.”

Thus far, nothing has been signed into law, Williams said, although there is “a moratorium bill that’s with the Virginia governor. That’s as far as one’s gotten so far.”

The Virginia bill would restrict the use of UASs by state and local law enforcement and regulatory agencies for two years while the commonwealth studies the issue. Some lawmakers had reportedly wanted to specifically prohibit state and local law enforcement from using UASs for warrantless searches, but instead the General Assembly, with overwhelming bipartisan support, voted to wait.

The bill has exceptions for emergencies, the National Guard, and “for purposes other than law enforcement, including damage assessment, traffic assessment, flood stages, and wildfire assessment.” It also does not address private use or research — a possible saving grace for the state, which is seeking to become one of the FAA’s six new UAS test sites. It is not clear whether Gov. Bob McDonald will sign the bill.

A Washington View column in the March/April issue of Inside GNSS will explore these issues in further detail.