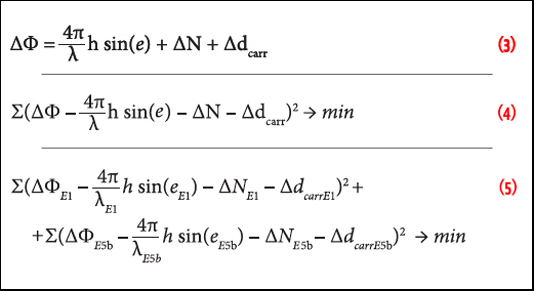

Equations 3, 4 & 5

Equations 3, 4 & 5Working Papers explore the technical and scientific themes that underpin GNSS programs and applications. This regular column is coordinated by Prof. Dr.-Ing. Günter Hein, head of Europe’s Galileo Operations and Evolution.

By Inside GNSS FIGURE 1: Proposal to have a single chip GNSS receiver with additional pins to allow for the inclusion of an additional radio

FIGURE 1: Proposal to have a single chip GNSS receiver with additional pins to allow for the inclusion of an additional radioQ: What will limit the spread of multi-frequency GNSS receivers into the mass market?

A: To set the scene, we need to define our terms of reference. By multi-frequency we mean receivers that operate with navigation signals in more than just the standard upper L-band from about 1560–1610 MHz where we find GPS L1, Galileo E1, Compass B1, and GLONASS L1. The obvious additional frequency is the lower L-band, from about 1170 to 1300 MHz, where again the same four constellations have signals.

By Inside GNSS

Navigation users may benefit from GPS modernization sooner than expected thanks to an apparent shift in the schedule of the modernized GPS ground control segment still under development.

The change means that full operational implementation of the new signals will come earlier in the delayed modernization of the operational control Segment (OCS).

By Dee Ann Divis FIGURE 1: Characterization of interference from the user perspective

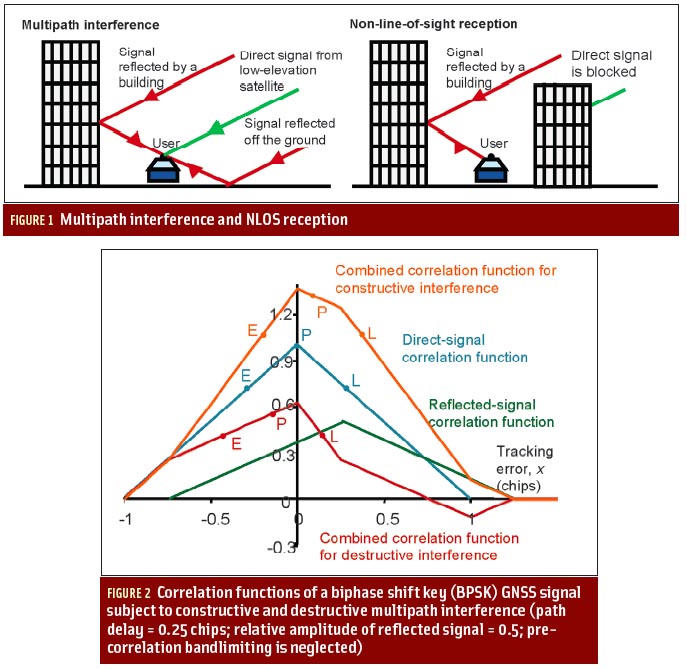

FIGURE 1: Characterization of interference from the user perspectiveIncreasing demand for ensuring the authenticity of satellite signals and position/velocity/time (PVT) calculations raises the need for tools capable of assessing and testing innovative solutions for verifying GNSS signals and PVT. Today’s civilian systems do not provide authentication at the system level, and a number of mitigation strategies have been developed in the last 10 years at user segment in order to protect receivers from interference and deception.

By Inside GNSS