Lowri Evans, DG GROWTH. Photo by Peter Gutierrez

Lowri Evans, DG GROWTH. Photo by Peter GutierrezAs ranking European Union (EU) official, Commissioner for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Elzbieta Bienkowska set the tone in a keynote speech that anticipated some major issues to be addressed in the upcoming “EU Space Strategy,” the EUropean Commission’s next big new European space policy document, expected to come out later this year.

As ranking European Union (EU) official, Commissioner for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Elzbieta Bienkowska set the tone in a keynote speech that anticipated some major issues to be addressed in the upcoming “EU Space Strategy,” the EUropean Commission’s next big new European space policy document, expected to come out later this year.

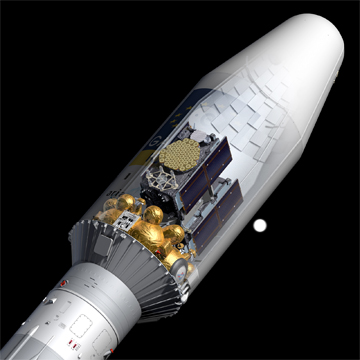

Bienkowska started by reminding conference goers that the event was taking place just days after the successful launch of two new Galileo satellites from French Guyana. The launch, she said, means there are now 14 Galileo satellites in orbit, and while one unnamed critic outside the room said, “Yes, but how many of those are actually working?” Bienkowska is at least technically correct. There are in fact 14 Galileo satellites now in orbit, and with more coming this year, the EU does expect to be able to follow through with its launch of initial Galileo services in 2016.

“I’m really proud of these achievements,” Bienkowska said. “Now we must convert them into useful products and services.”

She referred specifically to the “digital future” and space’s place in that future. “We must work hard to promote this in the space sector, in support of digital public issues but also to keep the EU space industry competitive.”

She also spoke to the importance of the “long-term sustainability” of Galileo and its strategic and dual-use aspects. “We need to ensure the security of our space assets and underline the role of the EU as a global player in space.” To this end, she said, the agencies (The European Space Agency – ESA, and the European GNSS Agency – GSA) need to work together.

In short, the space commissioner said all the right things in the right tone, setting the stage for another cracking edition of Europe’s salute to Space Solutions, this time with a complete Space Policy day tacked on for good measure.

Going the Distance

Comments outside the big room were almost as interesting as those inside. One official, who preferred to remain unnamed, said there was one word in particular in Bienkowska’s speech that could be read as a direct challenge to ESA.

“Sustainability,” the way Bienkowska meant it, said this observer, is going to be something of a new test for ESA: “You want to put a lander on a comet? ESA can do that. You want to build 30 satellites and place them in orbit? ESA can do that, too, but with these kinds of standard traditional space projects, generally speaking, you do the job, the goal is achieved, and the mission is over. But what Bienkowska is saying now is that we need to complete the Galileo system, and then we also need to continue to work together to fund it, maintain it and keep it running into the indefinite future.”

This message of sustainability-as-never-ending-service was repeated by a number of European Commission (EC) speakers during the conference, essentially describing guaranteed continuity of service as a precondition for European space business.

Philippe Jean, head of unit for Galileo and EGNOS Applications, Security and International Cooperation at the European Commission, said the new Space Strategy would set a framework and a direction for Galileo, among other programs, “for years to come.” He said, “We are going to complete it and ensure continuity, so it can be used by companies and citizens.”

Pierre Delsaux, the EC’s deputy director general of the Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) known more succinctly as DG GROWTH, linked continuity more explicitly to investment and returns.

“We need to find a way to combine public support with private money if we want EU space to continue for many years,” he said. “If we want European companies to continue to do business in space, we need to ensure that space will continue to be in Europe.”

And that means, he added, “predictability is key. . . . Decisions taken now in this sector are for 5, 10, 20 years into the future.”

So, businesses and other users need to feel confident that Galileo services are not going to go away; thus the new Commission emphasis on sustainability, continuity and predictability.

But is that all Europe needs? Lots of opinions were expressed on that score. Europe, it turns out, is very good at studying and understanding how and why things work, and why a thing doesn’t work, including itself.

As at previous such events, plenty of European self-analysis and self-criticism was on offer. For example, Didier Schmitt of the European External Action Committee said, “We are not pro-active, we are institution-centric, we are government-centric. We wait to see what the government is going to do for us, and that hinders innovation.”

Such comments tend to draw nods of agreement and are likely reassuring, helping the European space community feel more secure in being able to understand its own particular challenges, but perhaps also creating a sense of unity and identity. “We Europeans are alike and unified in our particular challenges,” such comments remind our hosts. And in unity there is strength . . . or at least comfort.

Others, such as ESA Director General Johann-Dietrich Wörner, would like to see Europe uniting around a more positive message. More on that later.

How about the Money, Honey?

But while we’re still on the subject of challenges, the problem of money, or lack thereof, as foreshadowed by Delsaux, raised its ghastly head.

As DG Growth Director General Lowri Evans noted, “The shift from building hardware to building space applications is going to be huge.” And, she made it clear, the EC is going to do its darnedest to create conditions under which businesses can profit.

However, she said, “We have a bit of an investment problem. More venture capital went into the space sector last year than in the last 15 years put together, but most of that was in the U.S., not so much here in Europe.”

This is not a new discovery. Commentators high and low have been pointing out this deficiency for some time now, as we have often reported. Most everyone agrees that the lack of European venture capital, based on culture and mentality and all that elusively subjective stuff, certainly when compared to the United States, is really a very big deal.

Evans spoke about devising new funding instruments, new research instruments, new instruments of all kinds, to try to make up for the missing venture capital, as has GSA Executive Director Carlo des Dorides.

So far though, Europe continues to lag behind, not only in terms of space investment, but also in terms of real downstream profits.

Speaking to us between sessions, Rainer Horn of SpaceTec Partners, who recently published an interesting report full of new ideas about funding the space business in Europe, said, “We have to stop this fantasy about somehow finding more European venture capital. It’s not going to happen. We can still do something, but it has to be based on a European model. We are Europeans and we are working in Europe, not in Silicon Valley.”

Horn believes solutions can be found, but it needs a big dose of European ingenuity and a willingness to jump out of old ruts. The bottom line is that it’s time to stop moaning and move forward.

Time for a Boost

On cue, TomTom co-founder and inspirational guy Pieter Geelen wowed the crowd with his twisting and turning tale of a little Dutch barcode reader company that grew into a global satellite navigation super-giant. TomTom is not slowing down, he said, developing new services based on “big data,” car-to-car communications, Earth observation (EO) satellite technologies and some truly intelligent ideas to help drivers avoid and even predict traffic jams, find parking spaces, and much more, services that are already feeding into the autonomous vehicles market.

After his talk, Geelen told us he agrees with the EU’s decision to invest in and build its own satellite navigation system. “It’s about taking control,” he said. “GPS can still be turned off, and that would be a disaster for all of us. With what we are going to get back in terms of benefits, we could pay to build Galileo many times over.”

A second inspirational tale came from Planet Labs Co-founder Robbie Schingler, whose (American) company produces surprising numbers of miniature satellites called “Doves” that scan the earth continuously at a high level of visual resolution.

Schingler said he started the company in his garage with $200,000 and, after a sequence of keen insights and quick reactions, less luck that you might imagine, and, later, you guessed it, a hefty input of venture capital, he and his partners built Planet Labs into, well, quite an impressive venture. Just to show us how it’s done.

Dual Use, Do-Over?

For some of the participants at the event, particularly those at the “Space and Security” session, making full use of Europe’s limited resources, including money, means making every possible use of every asset, and at the very least making “dual use” of Galileo, as in both civil and defense-related use.

Rint Goos, deputy chief executive of the European Defense Agency (EDA), said, “NATO is the European defense organization, but NATO also needs a Europe that can bring capabilities to the table.” One such European capability, he suggested, could be a secure and robust satellite navigation system.

However, he added, “We can only spend taxpayer money once; so, we need to find synergies in all that we do. We need to approach the question of dual use of all systems before we start building those systems, methodically and from the point of conception, not when these systems are already in place.”

Jeremy Blyth, chairman of the Galileo Security Accreditation Board, essentially agreed with Goos’s observation about building features in, saying, “The concept of security needs to be embedded from the beginning. This was not done with Galileo and that was a mistake and we have paid the price in terms of delays.”

While Blyth would not elaborate on which delays he was referring to, we can suppose that he meant delays in the specification of parameters and operational procedures for the secured Galileo Public Regulated Service (PRS), a service designed to be accessible only to authorized governmental bodies.

About the PRS, Blyth said, “It should be the world’s secure system of choice. We need to do this, to make the PRS the best there is.”

There seemed to be a split in thinking about who needs to agree on what.

Goos said he thought national governments needed first to debate the question of whether Galileo should be a dual-use system or not.

Blyth said he wasn’t sure anyone, including himself, knew what the term “dual use” meant. He continued nonetheless, seemingly answering his own question, “Galileo is a dual-use system. It will be used by civil and defense users. What we need to do is to protect the service to the required level, and this means security. Various parties must join together to deliver secure service for Europe. We want to be the focal point for how to secure a space service.”

Member of European Parliament and staunch space champion Marian-Jean Marinescu said, “Dual use means civil control but delivering service that meets defense needs. So, we need defense coordination, agreement between a defense coordination body and Galileo, Copernicus, etc.”

ESA’s Marco Lisi, speaking from the audience, asked “Why not get the EDA and Galileo together? Security-wise, Galileo is already the most advanced EU space system.”

For a moment, getting more people together seemed to be the consensus first step. Indeed, thanks to a handy voting gadget, the audience as a whole voted for involving more actors at the EU member state and European levels in the question of defining and putting into practice a dual use scenario.

The tide seemed to turn again, as Blyth retorted, “Good luck with that, because member states’ governments have yet to have this debate even at their own national levels.”

Marinescu said, “Bring together the Member States? For what? Copernicus and Galileo are already European systems,” meaning the interests of all relevant member states are already represented within these programs.

Meanwhile, Marinescu said, Europe needs to optimize existing space, defense, and security-related systems. “There are in fact lots of parallel systems — member states have them, and there are private systems. We need to bring these together.

“We must secure the system — ground and space segments,” Marinescu continued. “And then we must secure the product, the signal. But before anything, we need a common European policy on defense and security.”

What’s more, Marinescu pointed to the need for a fundamental re-think, perhaps within the framework of a new “joint undertaking,” bringing industry and relevant stakeholders together with the EU to hash the whole thing out, once and for all.

Talk about starting over.

So, not much was resolved on the question of Galileo and dual use, but perhaps a few more people are now thinking about it.

Marinescu reiterated the importance of inter-institutional cooperation, involving our old friends. “ESA, the European Commission and the GSA should be together on this,” he said, “working towards the same goal — right now, the way things are going, cooperation between these three is not so nice, not such a good situation.”

Space Goes On

Marinescu’s comment about the current bad “situation” with respect to interagency cooperation does not mesh with what has been said recently by the likes of the GSA’s des Dorides and ESA’s Director of Galileo Program and Navigation-related Activities Paul Verhoef, and they would know best.

For his part, ESA Director General Johann-Dietrich Wörner said he is still and has ever been ready and willing to work hand-in-hand with the GSA and European Commission.

“United in space,” he said, “we are ready to continue to work together with the Commission, with Member States, with industry and citizens.”

The end of 2016, he said, would see the all-important ESA Ministerial Council reviewing ESA’s new proposals, among which will figure a new ESA-GSA accord on Galileo working arrangements.

“ESA is the space agency serving the European Union,” Wörner insisted, “supporting a European spirit and identity.”

He also addressed the question of return on investment. “What is the final currency?” he asked. “Is it dollars, euros?” He then asked the conference to remember the “Apollo effect,” and all the positive ramifications of the early bold endeavors in space. “Remember the prestige that was gained, and the way it stimulated our imagination and motivated our children to study science,” he said.

Pioneering and discovery is part of Europe’s history and heritage, Wörner argued, and space still has a part to play in the hard-to-quantify arena of human inspiration.

Wörner closed his presentation by citing Michael Faraday who, when asked by a government official what his discovery of electricity was good for, replied, “I don’t know, but you will tax it.”

The Space Solutions conference was to be the last big to-do of the Netherlands EU Presidency, which runs through June 2016. EU Member States, now numbering 28, hold the office, one after the other, in a known order, for six months each. Slovakia is next up, to be followed by Malta and then the UK.

Each presidency has some freedom in terms of the issues it wants to highlight and specific initiatives it wants to launch or pursue.

With its sponsorship of a really big space conference in The Hague, and by hosting ESTEC and now the GSA’s new Galileo Reference Center in Noordwijk, which will certainly be a lasting legacy of its presidency, the Netherlands has made a clear and bold statement about its commitment to the EU space sector.

Here’s hoping the incoming Slovakian presidency will want to leave a similar mark and will do as much to promote EU space activities. This seems a likely prospect, with Slovakia’s current EU Commissioner being the strong space advocate Maros Sefcovic.

When first named Commissioner for Energy Union, Sefcovic, who is also Commission Vice-President, was expected to keep at least one foot in space in support of Elzbieta Bienkowska. She hasn’t seemed to need much support, now coming through in her own right as a formidable voice for the European space community. Still, we expect Sefcovic to return to the space policy front lines during the Slovakian Presidency, and, judging by past performances, his contributions will be welcome.