Just when they thought it was safe to go back into space . . . .

The Russian GLONASS system, which had appeared to be recovering from a series of organizational and technical problems in recent years, appears to have suffered a systemic disruption during the past 24 hours — beginning just past 1 a.m. Moscow time on April 2 (UTC+4) — 6 p.m. EDT on Tuesday (April 1, 2014).

Just when they thought it was safe to go back into space . . . .

The Russian GLONASS system, which had appeared to be recovering from a series of organizational and technical problems in recent years, appears to have suffered a systemic disruption during the past 24 hours — beginning just past 1 a.m. Moscow time on April 2 (UTC+4) — 6 p.m. EDT on Tuesday (April 1, 2014).

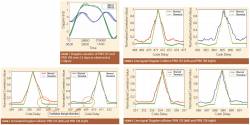

Outages continued for more than 10 hours, with the Russian GLONASS monitoring center showing satellites in unhealthy statuses: “failure” and “illegal ephemeris.” The first accompanying figure from the Russian Federal Space Agency Information-Analytical Center website shows this history, with pink and purple colors representing failure and illegal ephemeris, respectively.

Because the failure was systemwide and simultaneous, some have speculated that an incorrect uploading of corrections to satellite ephermerides (orbital positions) occurred. The staggered restoration of satellite health in the hours following the outage reflects the need for GLONASS system operators to wait until each satellite passes within range of ground stations on Russian territory to be reset.

In the second figure, test data coincident with the GLONASS ephemeris disruption of April 1/2, provided to Inside GNSS by Frank van Diggelen, vice-president of technology for Broadcom Corporation, show conclusively how a GPS/GLONASS/QZSS/BeiDou receiver survives the complete disruption of one of the constellations during tracking in "a large East Asia city."

The figure shows data from two receivers from two different manufacturers, both in smartphones. The yellow dotted line indicates the path of a GPS/GLONASS receiver; the blue dotted line is from the Broadcom 47531 receiver, which tracks GPS/GLONASS/QZSS/BeiDou signals simultaneously.

The latter receiver includes logic to use redundant measurements to check the validity of all measurements and successfully identified and removed the bad GLONASS ephemeris 100 percent of the time, as can be seen by the continuity and accuracy of the positions.

The problem marks another setback for the Russian GNSS program, which saw the system rebuilt and modernized over the past decade but has stumbled in recent years due to launch failures (including triple-satellite losses in July 2013 and December 2010) and organizational problems, including dismissal of high-ranking space officials in the wake of the launch failures and for charges of corruption. In one case, the Proton rocket failure was blamed on a premature launch and in another on overfilling of the launcher’s fuel tanks.

Successful launch of a GLONASS-M satellite just over a week ago had seemed to indicate that the program had regained its footing. Yesterday, Nikolai Testoyedov, director general of the GLONASS satellite manufacturer, JSC Reshetnev Information Satellite Systems, announced that the long-awaited launch of the second next-generation satellite — GLONASS-K — would occur at the end of this year.

Also yesterday, Russian lawmakers endorsed draft legislation to allow the country to set up a GLONASS monitoring facility in Nicaragua, according to the RIA Novosti news service. This would add to the handful of monitoring stations, including sites in Brazil and Antarctica, outside the Russian territory, which are essential to managing a constellation in situations such as just occurred with GLONASS.

A proposal to establish GLONASS monitoring stations in the United States was recently rebuffed by the U.S. Congress.

The U.S. Global Positioning System has never experienced a systemic outage as occurred with GLONASS and has a notable record of robustness, resilience, and rapid information dissemination. However, its space segment has not been flawless. GPS SVN49, a Block IIR-M satellite with the first L5 signals, experienced anomalies that have taken it out of healthy status since 2009 and incidents of satellite clock drift or runoff have occurred over the years that caused temporary degradation of user range error. But GPS systemwide errors by the operator — the U.S. Air Force — have been essentially nonexistent, at least from the perspective of users.

before launch.jpg)