Over at least half a dozen years the GPS III Follow On program has taken a number of dramatic turns only to wind up, in true soap opera fashion, with the same leading characters headed to the altar.

At the end of the latest episode, the field of suitors for the multi-billion-dollar GPS IIIF contract narrowed suddenly in April when two of the three corporate hopefuls abruptly left the field.

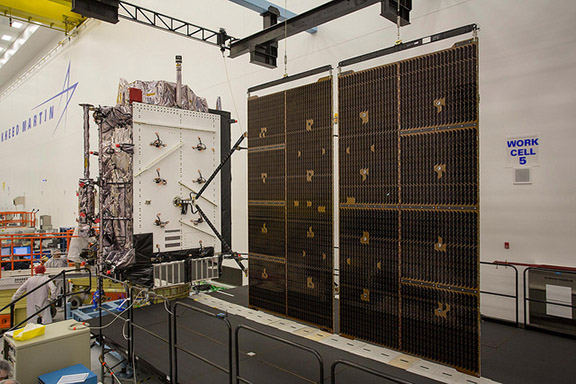

The last one standing was Lockheed Martin, the prime contractor for the current tranche of GPS III satellites and a company that has been sharply criticized for several schedule-warping problems during that spacecraft’s development. The Air Force was so unhappy that, at one point, it blocked the firm from participating in a portion of its then-planned GPS III re-compete.

Now, however, the Air Force and Lockheed are looking forward to a long, 22-satellite relationship. Though the negotiations on the new contract were still ongoing as of press time, according to sources, the Air Force has apparently rediscovered what others have learned the hard way — it’s often more advantageous to stick with the partner you have.

Faster and Cheaper

The surprising shift in the approach to GPS IIIF is the result of self-reflection on how the Air Force builds satellites, according to sources. The commercial satellite industry has proven it can construct spacecraft faster and cheaper and the Air Force wants to do the same. The GPS Directorate had already said in 2017 that it would contract with just one company for all of the IIIF satellites as a way to avoid issues with a redesigned spacecraft. Then a study undertaken earlier this year, a source familiar with the issue told Inside GNSS, showed how sticking with its existing contractor could bring costs down as well as speed deployment.

The rough goal, said the expert, is to cut the time to build a IIIF satellite by roughly 25 percent — going from around 5.5 years to 4 years. If you can do that you will save money in a number of ways, said the source, who spoke anonymously to be able to discuss the matter.

First, they said, by contracting for a shorter period of time you’re reducing the period of time for which you are paying for contractor overhead. Moreover, in order to meet the shorter turnaround, it’s necessary to change the way you think about testing — which is one of the more expensive aspects of a satellite program.

“In fact,” said the expert “that’s one of the big reasons the civil community does so well. The testing is very short.”

The approach to testing is indeed one of the factors that distinguish a commercial project from a government one, said Leanne Caret, president and CEO of Boeing Defense, Space & Security.

“The test program under government oversight is different than under commercial oversight,” Caret told the 34th Space Symposium in April, “and it doesn’t mean that the commercial processes are any less robust.”

Even if you don’t adopt a commercial testing approach, said the source, sticking with the same contractor ensures you don’t have to deal with new testing regimes.

“Everybody tests a little bit different,” the expert explained, “even though the numbers have to come out the way they’re supposed to. Every company has different processes and those processes take time. When you start with somebody new… the efficiencies aren’t there because they haven’t the lessons learned.”

Inside GNSS did reach out to the Air Force about potential changes in testing and other questions about GPS IIIF going forward, but the service was unable to respond by press time.

Sticking with an incumbent also reduces development risk, said Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at think tank CSIS. “Whenever you start over with a new satellite, even if it’s based on an existing satellite design, you know that you are adapting a new satellite bus — you incur all kinds of risk.”

There is also real savings in sticking with the incumbent because the processes to get things done are simpler. “When you continue the contract in a sustainment mentality, you just don’t have all these rules and regulations,” said the expert.

For example, when you do a re-competition “you can’t buy the long lead parts; which costs you money. You have to wait until you can buy them until the contract is let,” the source said. “There’s about four or five other things that can’t be done until after the decision is made on who the contractor is. Where if you know you’re going to have a follow-on contract, within the current contract, you can make provisions to get some of those key components.”

Just avoiding these kind of delays can shave 18 to 36 months off the schedule, the source said.

Harrison, who is also CSIS’s director of defense budget analysis, suggested the Air Force discovered it just wasn’t worth changing partners.

“Maybe they started looking at the track record of space acquisitions where the Air Force has a long history of awarding follow-on contracts to a new company, awarding against the incumbents. And maybe they started to realize that, ‘Hey that’s not good’ — that we can leverage all of the pain and suffering we’ve been through with the new-design GPS III satellites, we can just keep that going and evolve it and build more of them rather than starting over.”

Moreover, he said, “if you’re going to make schedule a high priority, but you don’t want to pour lots of money into it, then that favors the incumbent. They have a hot production line.”

Outside Pressure

There were other factors as well. Like most relationships, the one between Lockheed Martin and the Air Force did not exist in a vacuum and there was certainly pressure from the Air Force”s extended, federal family.

The Government Accountability Office has issued a series of reports about cost overruns in the service’s space programs citing, as prime examples, the lagging and often over budget GPS space, ground and user equipment development efforts. The 2016 declaration of a Nunn-McCurdy breach in the Next Generation Operational Control System (OCX) ground system only flood-lighted the problems for an already unhappy Congress, which is now pushing the Air Force to reorganize its approach to military space acquisitions.

There has also been peer pressure of a sort. That is the decision to speed up GPS modernization was likely driven, in part, by the change in the threat environment created by Russia and China, which are near-peers in space technology.

“In the recent past, the United States enjoyed unchallenged freedom of action in the space domain,” said Strategic Command Commander Gen. John Hyten, in an April 2016 statement on the release of the new Space Enterprise Vision (SEV). The SEV frames how the U. S. will address the threat posed by other space-capable nations. “Most U.S. military space systems were not designed with threats in mind, and were built for long-term functionality and efficiency, with systems operating for decades in some cases. Without the need to factor in threats, longevity and cost were the critical factors to design and these factors were applied in a mission stovepipe. This is no longer an adequate methodology to equip space forces.”

“The potential adversaries we have around the world know very well how important space is to us and how important it is to our alliances and to our partners and how we would operate and fight,” said former Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James. China, in particular, has been watching and learning from U.S. space operations for the last 25 years, James told a September CSIS symposium on organizing military space.

China is working hard to expand its military capabilities in space, say defense officials, and thwarting GPS is one of the things on which they are focusing.

“The PLA (People’s Liberation Army) is acquiring a range of technologies to improve China’s counter-space capabilities,” the Department of Defense (DoD) said in its annual report to Congress on military and security developments in China. China was working on directed-energy weapons and satellite jammers, DoD wrote, and navigation satellites were among the targets suggested in Chinese PLA writings.

“In the not-too-distant future, they (the Chinese) will be able to use that capability to threaten every spacecraft we have in space. We have to prevent that, and the best way to prevent war is to be prepared for war,” Hyten told an audience in January at Stanford University in California, according to a DoD summary. “So, the United States is going to do that, and we’re going to make sure that everybody knows we’re prepared for war.”

More Is Better

Hyten, who is now leading Air Force Space Command when the SEV came out, told this year’s Space Symposium that the biggest advantage the U.S. has in space is the “sheer mass and unbelievable capability that we have built.”

While the importance of those on-orbit assets mean they are likely targets, having a mass of spacecraft in place could also serve as a deterrent, suggested the expert.

Commercial operators like Iridium have spacecraft in orbit that they can move into place when needed, pointed out the source. The GPS constellation has spares too, the source said, five — plus another five that are not in as good a shape but could still be useful in a pinch.

“It (a backup) only has to last until the next time you launch,” the expert said.

The source believes the Air Force will launch the new GPS III and GPS IIIF spacecraft quickly and not wait until the satellites now on orbit need to be replaced — as has been the practice in the past. Those older satellites will be turned off but will be available as backups, the expert said. Given the number of planned GPS III spacecraft the constellation will be more than twice as big as it needs to be and “that’s a big problem when it comes to thinking about how you are going to target those things.”

The minimum for the constellation is 24 and one only needs to see four satellites for a navigation solution, the source pointed out.

“So you can zap a lot of GPS satellites before it really matters,” the expert said.

Moreover, with the advent of other new satellite navigation constellations there will be even more spacecraft available, spacecraft with separate ground systems, to provide satellite navigation service in an emergency.

With targeting the GPS constellation made so much more difficult, would an adversary risk the consequences? Perhaps not. The U.S. has made it clear that any attack on its space assets will be met with a strong reaction.

“Our national security strategy states that the United States considers unfettered access to and freedom to operate in space as a vital national interest,” Gen. John Raymond, commander of Air Force Space Command, told the Space Symposium. “It goes on to further state any harmful interference with or an attack upon critical components of our space architecture that directly affect that vital U.S. interests will be met with a deliberate response at a time place manner and domain of our choosing.”

Getting There

It’s an interesting plan, but will there be sufficient launch capacity both in terms of launch vehicles and launch sites to pull it off? Once you have the satellites can you get them on orbit?

All those who spoke to Inside GNSS about it said “Yes.”

“My feeling is that, if the demand is there, the supply will be there,” said Marcia Smith, a space policy expert who followed issues for the Congress as a member of the Congressional Research Service and is now the founder and editor of SpacePolicyOnline.com.

There are many more launch options for the Air Force now than there were in years past, she pointed out.

Orbital ATK has its new, large OmegA launch vehicle, she said, while United Launch Alliance (a joint venture of Lockheed Martin Space Systems and Boeing Defense, Space & Security) offers the Vulcan. Among the new space launch entrepreneurs is Blue Origin with the New Glenn launch vehicle and SpaceX with its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, and, in another four years or so, the BFR or Big Falcon Rocket.

There will also enough be enough launch capacity in terms of launch sites.

“SpaceX is building its own launch site down at Brownsville (Texas),” said Smith, “and if it moves forward with that there’s going to be a whole other set of launch sites and launch pads there, which will free up capacity at the Cape (Canaveral) and at Vandenberg (Air Force Base).” Blue Origin is also using one of the old Air Force launch pads at Cape Canaveral, she said, and the Air Force is looking at ways to automate and streamline their systems and processes to speed launches up.

“So I think that, of all the things that could impact the GPS schedule I would think that launch would be pretty low on the list schedule,” said Smith.

Moving On

Sources suggested that, in the end, the Air Force’s evolving priorities meant that requirements in the GPS IIIF Request for Proposal (RFP) were tailored in such a way that only the incumbent contractor could fulfill them — with one source saying that that shift was at least one of the reasons that the release of RFP was delayed for so long.

That theory is supported by the clear disappointment Boeing expressed in its comment about the contract.

“Boeing did not submit a proposal in response to the RFP,” said a company spokesman, “as the RFP emphasized mature production to current GPS requirements and did not value lower cost, payload performance or flexibility.”

“Just broadly,” said Northrop Grumman’s CEO Wesley Bush during a conference call on first quarter results, “the GPS decision had absolutely nothing to do with anything else going on in the space portfolio other than a relative comparison of the attractiveness of the different opportunities that we’re pursuing there.”

As of press time it appears that the disappointed contenders are unlikely to complain. Sources suggested that the focus on sticking with incumbents would favor both firms in other contracts and that the companies would win, if they had not already won, better-suited programs.

Congress also appears to be onboard with the new approach.

“If there was a major concern, and contractors were leveraging congressional advocacy, you probably would have seen something already,” said Mike Tierney, a senior consultant and budget expert with the defense, space/intelligence, homeland security consulting firm Jacques and Associates.

Though some questions have arisen, Harrison said he did not believe the long contracting process was an empty effort — nor was it a maneuver to pressure Lockheed to address its development issues and/or lower its prices.

“I don’t think it was a bluff,” said Harrison. “I think that they (the Air Force) were sincerely reaching out and trying to find alternative suppliers — and, you know, it didn’t work.”

“I think they started to realize it’s not worth it,” he said. “On the industry side it’s not going to be worth it and on the government side it’s not going to be worth it.”