A variety of organizations are cooperating to assess and address GPS-related vulnerabilities in the country’s critical infrastructure (CI). From receiver testing opportunities to community briefings and workshops the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) plus other civil agencies, industry groups and experts are working through options looking for the best way forward.

DHS’ Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) is offering a testing opportunity this fall formanufacturers of commercial GPS equipment used in critical infrastructure as well as CI owners and operators. Participants will be able to evaluate equipment in unique live-sky signal environments that are only legally possible to create under controlled conditions authorized by the U.S. Government. The deadline to apply for the program is July 20. More information can be found at Fed Biz Opps (FBO.gov) under solicitation number 70RSAT18RFI000011.

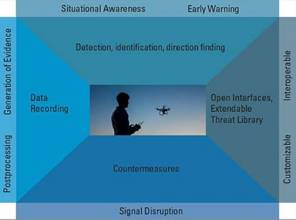

A similar opportunity is available for manufacturers of small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS) and commercial GPS equipment manufacturers supplying them. Such small UAS are increasingly used to inspect critical infrastructure. Participants will get a chance to demonstrate equipment in unique live-sky signal environments that require government authorization. The FBO.gov solicitation number is 70RSAT18RFI000012. The application deadline is August 3.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which is part of the Department of Commerce, held a workshop in June on CI timing solutions and interoperability. NIST scientist and workshop chairman Stefania Romisch, called assured access to accurate time “the hardest problem to solve.”

MITRE’s John Betz proposed a comprehensive plan during the meeting that would look at the different sectors and devise risk-informed approaches tailored to their needs.

“My perception,” said Betz, “is that timing is actually a whole collection of different applications with different requirements, different degrees of criticality, and so forth — and so you need to modulate what’s done based on the different subsets of the timing community.”

Called ANTSERR for Advanced Navigation and Timing Strategy for Enhanced Robustness and Resilience, the approach uses multiple inputs, a reduced reliance on GPS when it makes sense, and competent receivers.

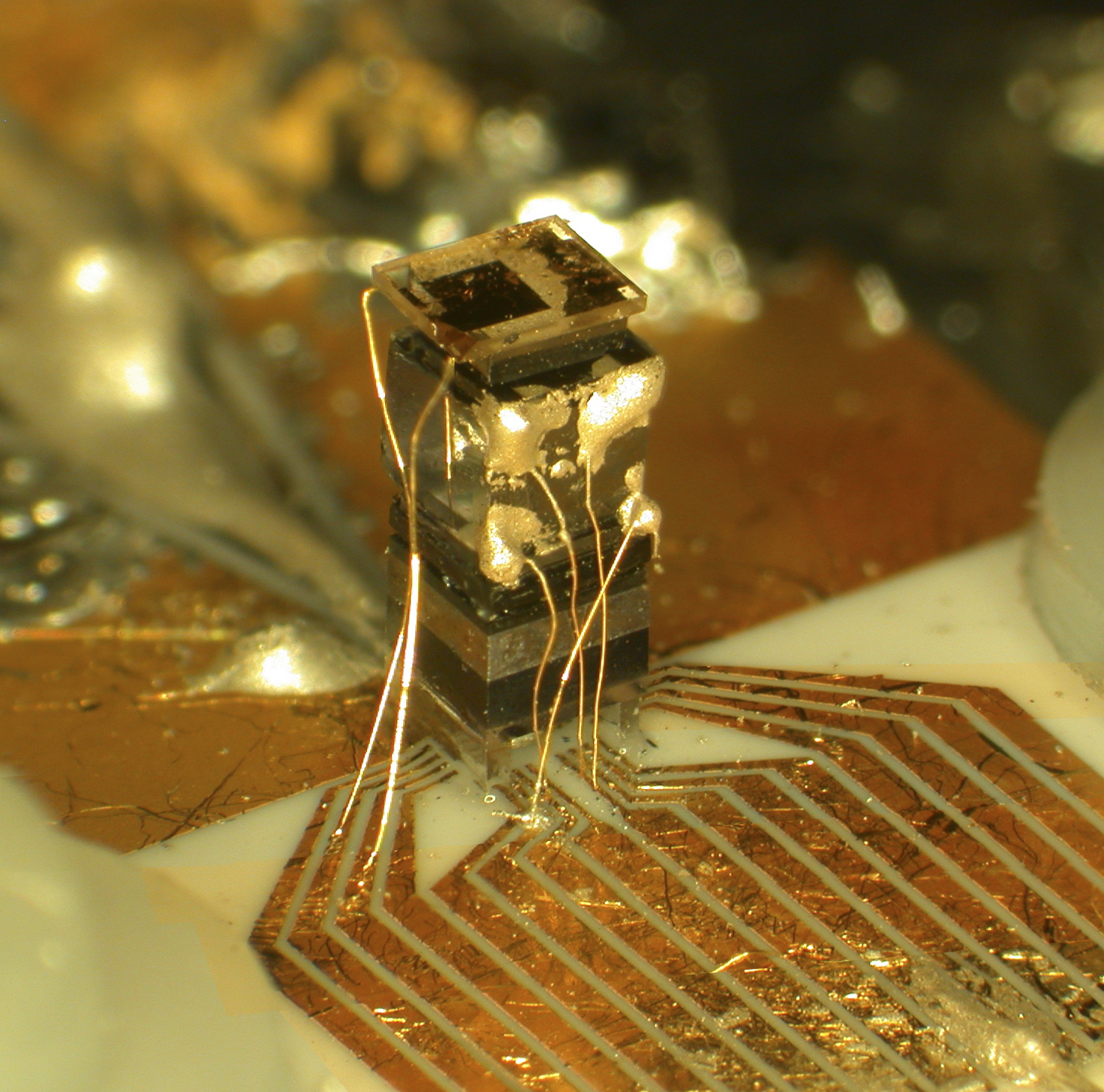

Competent receivers have a number of timing inputs, said Romisch in her slides, using uncorrelated time delivery systems. They degrade gracefully and have holdover capability.

They also have an element of common sense, Betz told Inside GNSS. “For example we hear about the receivers that have a glitch when there’s a GPS week rollover or a leap second insertion. We hear about the receivers on those ships in the Black Sea that knew they were on a ship but they reported that they were in the middle of an airport tens of miles way. We think about the receivers at the ION (GNSS+) conference last September when a simulator was generating signals and they went back three years in time and moved 5,000 kilometers in a second.”

Time doesn’t go backwards, he said, and a terrestrial receiver is not going to move thousands of kilometers in a second— these receivers lacked common sense.

“It doesn’t mean that they have to be able to handle every attack but it means that, at least when something is funny, they ought to behave in a reasonable way,” Betz said. “Right now we’ve got receivers that have not been specified or designed or tested to be competent in these ways.”

To support this he suggested an organization that would test and rate receivers for their ability to handle such problems.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if an independent organization could evaluate different devices that are on the market and give them the same kind of five star rating that we get with automobile crash testing? That would inform organizations … would inform critical infrastructure owner/operators as to what are the better receivers to buy and which are the poorer receivers to buy.”

Such an organization would have to be created, he said. Once in place it would create natural market pressure for better products to be available.

The $1 million question, he said, is determining what is really needed in terms of timing accuracy, service region (coverage) and an ability to resist threats.

“My understanding is that DHS and other civil agencies have actually been trying to do that in an organized way over the last year,” said Betz. “It’s complicated and difficult to do that. But I think it’s absolutely needed that we understand, from a systems engineering perspective, what kind of capabilities we need and then we can trade off how best to get them.”

It needs to be possible to identify and remove threats to receivers, he said, and, in the best of all worlds, the system would have cybersecurity at the same level as the still-developing GPS ground system.

He also suggested diversifying and adding timing sources. This could include adding in signals from other satellite navigation constellations and providing time over fiber or via cesium clocks. The clocks would be disciplined using GPS and therefore be able to maintain the appropriate level of accuracy over an extended period but they could operate without GPS for days, even months.

“GPS is going to be the foundation for navigation and timing in our nation for as far in to the future as we can see,” said Betz, “but that doesn’t mean it needs to be used by itself and it doesn’t mean that it needs to be used everywhere where it’s not needed.”

A backup system is also a possible element. The British have demonstrated that eLoran can deliver time with 50 nanoseconds accuracy or better “pretty much anywhere you want to,” said Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation.

ELoran “might be part of the solution,” Betz said, adding it would be necessary to look at the specific configuration including the number of towers, where the towers are and the redundancy that’s been built into the system.

“Ultimately, at the end of the day, we may end up with not needing any additional infrastructure,” said Betz, “maybe it all can be solved without it or maybe we end up with an infrastructure that falls short in some of these target areas. But at least we ought to think about what we would like to have and then we’ll understand what we can afford to have and what we need to have.”