Sen. Al Franken

Sen. Al FrankenLess than 90 days after government watchdogs reported drivers are not being clearly informed about privacy risks posed by vehicle-location data, the head of the U.S. Senate’s privacy committee announced legislation to give consumers more control over how information about their whereabouts is collected and used.

Less than 90 days after government watchdogs reported drivers are not being clearly informed about privacy risks posed by vehicle-location data, the head of the U.S. Senate’s privacy committee announced legislation to give consumers more control over how information about their whereabouts is collected and used.

Sen. Al Franken, D-Minnesota, announced last Thursday (March 27, 2014) that he would introduce the Location Privacy Protection Act of 2014, a broad measure requiring private companies to get permission from users before collecting and sharing location data from devices including smartphones, tablets, and in-car navigation devices. The bill would put the burden on companies to get explicit customer agreement before collecting their location information as opposed to setting up tracking by default and requiring the consumer to opt out.

The bill would also make it easier for consumers to change their minds. It would require companies collecting geo-location particulars from more than 1,000 devices to post information on the Web about the kinds of details they are gathering, how they share and use them, and how people can revoke their consent, according to language obtained by Inside GNSS.

Consumers’ location data is worth a great deal to firms trying to reach customers as they move through their day — particularly while they are shopping or are using their phones to search for services such as a good meal. Asif Khan, founder and president of the Location Based Marketing Association told Inside GNSS last summer he expects location-based advertising to grow to $6 billion by 2015.

Location data could become even more valuable over the next few years as advertisers target multi-screen campaigns — coordinated messages to customers as they jump from looking at their desktop, to their cell phone and tablet to view digital ads while riding the elevator, sitting in a cab, or filling up their gas tanks.

An August 2013 survey by the Association of National Advertisers and Nielsen found that two-thirds of marketers spent up to 25 percent of their media budget on integrated multiscreen campaigns last year, according to a report on emarketer.com, and 88 percent of survey respondents expected such campaigns it to be very important to their marketing by 2016.

Proposed Law May Lag Behind Technology Developments

Individual consumers can be identified across devices through their accounts with social media such as Facebook or queries to services (e.g., Google) linked to their electronics. They may also be connected through location, suggests Screen Media Daily, in a white paper posted on the LBMA website.

The bill fails to take such new developments fully into account, Kahn told Inside GNSS in an emailed comment.

“This bill is short sighted in that it narrowly addresses the over-simplified view that location privacy pertains only apps,” wrote Khan. “What about digital screens that change their content to reflect the interests of passersby and beacons in stores that recognize nearby consumer devices and respond with a Bluetooth offer? What about video camera’s that have been tracking us for years for security and loss prevention purposes and are now are being used to track our movements and faces?”

“Consent is a must,” said Khan, adding that “those collecting data, should be clear on how it will be used, stored, and commercialized.” Moreover language should be added to address what happens to data when a consumer no longer wants a service, he added.

But Khan suggested that some of the provisions may hamper the industry and do a disservice to consumers in the process

“As the global industry association, we support the general principles of the proposed Location Privacy Protection Act, but feel that this may go too far in hindering the economic development of our industry,” Khan said. “The reality is that location-based marketing is here to stay and it’s valuable to both the consumer and the corporation. New business models are emerging whereby the consumer is recognized the value of their data and will get paid for sharing it!”

Targets Stalking, Other Misuse of GNSS

The bill, however, is about more than setting limits for consumer privacy. Franken is also seeking to protect battered women and others at risk by banning the creation and distribution of “stalking apps,” software that enables someone to track a person without his or her knowledge.

“When I started investigating this as the chairmen of the subcommittee on privacy the first testimony I received was from the Minnesota Coalition for Battered Women,” said Franken said in a video discussing the bill. “They told a story about a woman in St. Louis County who went to a county building to go to a domestic violence program there and on her smart phone she got a text message from her abuser asking why she was at the county building. Well, she was really scared, so they took her to the local courthouse to get a restraining order. And when she was at the courthouse she got another text message and this one said ‘Why are you in the courthouse? Are you getting a restraining order?’”

Her abuser was able to follow her every move with a stalking app, said Franken, noting that creators of such software advertise it that way. According to the U.S. Justice Department, more than 25,000 cases of GPS stalking occurred in 2006, said Franken, the most recent year for which data is available.

“Think of how much the use of smart phones has exploded since then,” he said.

The legislation, which is co-sponsored by Chris Coons, D-Delaware, and Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, proposes to not only ban such software but also make obtaining geo-location fraudulently a criminal act punishable by imprisonment. Proceeds from stalking software would be seized and used to fund help lines and emergency services as well as training for law officers and those who work with victims.

Franken, who is the chairman of the Senate Privacy, Technology, and the Law Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, is proposing to add teeth to his bill by giving the U. S. attorney general the power to enforce the protections for consumer location data. The penalties for violating the Act could be severe. Franken proposes fines and punitive damages of up to $1 million total for a violation with up to an additional $1 million if the violation was willful or intentional.

Franken has been an advocate for privacy protection and introduced the Location Privacy Act of 2012 (S. 1223). It was approved by the Judiciary Committee but never voted on by the full Senate.

GAO Report Underlines Vehicle-Related Issues

Whether this year’s legislation will fare any better remains uncertain, but the new bill comes after disclosures by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden have sharply raised public awareness of surveillance. including the gathering of location data. It also follows on the heals of a Government Accountability Office report released January 6 detailing shortcomings in how car companies and location services gather, store, and share location data.

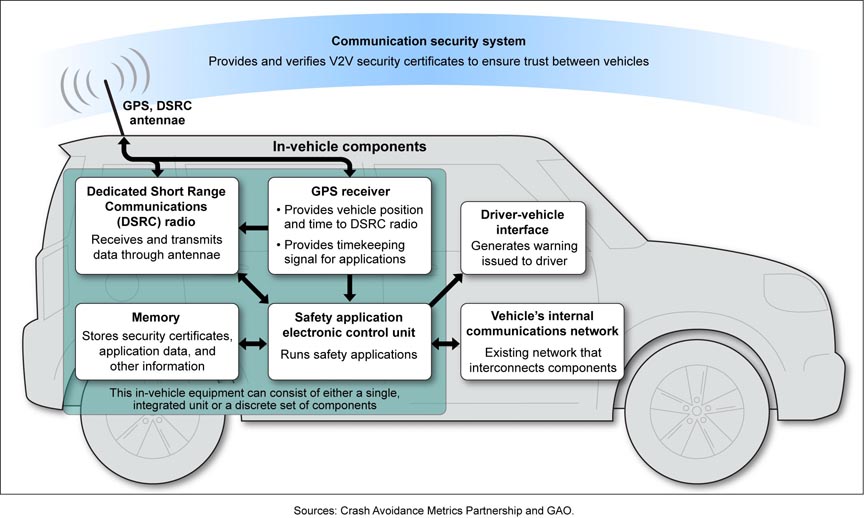

In its report, IN-CAR LOCATION-BASED SERVICES — Companies Are Taking Steps to Protect Privacy, but Some Risks May Not Be Clear to Consumers (GAO-14-81) the agency looked at 10 companies that were major players in their industries: Chrysler, Ford, General Motors, Honda, Nissan, Toyota, Garmin, Tom Tom, Google Maps and Telenav. The six auto manufacturers between them had nearly 75 percent of the new car sales in the United States in 2102. The other four comprise two portable navigation device firms and two mapping and navigation app makers. GAO also talked to third-party service providers used by the companies.

Overall GAO found that the companies had implemented steps that were consistent with some, but not all, industry-recommended privacy practices. Some of the steps “were, in certain instances, unclear, which could make it difficult for consumers to understand the privacy risks that may exist.”

All the companies, for example, had protections in place for the location data they gathered, but none of the firms allowed consumers to delete their data and the firms sometimes stored it for years. The companies also used different ways to “de-identify” the data. Some of these “anonymizing” techniques, which included practices that removed names but linked data to a unique identifying number or vehicle, could make it harder to keep consumers’ identities secret.