Universities must declare by August 22 if they will seek to lead a new federal research effort on unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), a contest that is expected to be fiercely competitive despite the low level of funding guaranteed for the program so far.

Universities must declare by August 22 if they will seek to lead a new federal research effort on unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), a contest that is expected to be fiercely competitive despite the low level of funding guaranteed for the program so far.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is looking for a coalition of academic institutions, supported by partners and the private sector, to form the core of a new Center of Excellence for UAS. Once selected the COE will work with the FAA for at least 10 years, conducting research critical to integrating unmanned aircraft into the national airspace system (NAS).

Proposals are due September 15, and the FAA said it expects to make its choice by early 2015 with operations to start as early as that summer but no later than September 2015. The final solicitation and rules can be found at online at the FAA website.

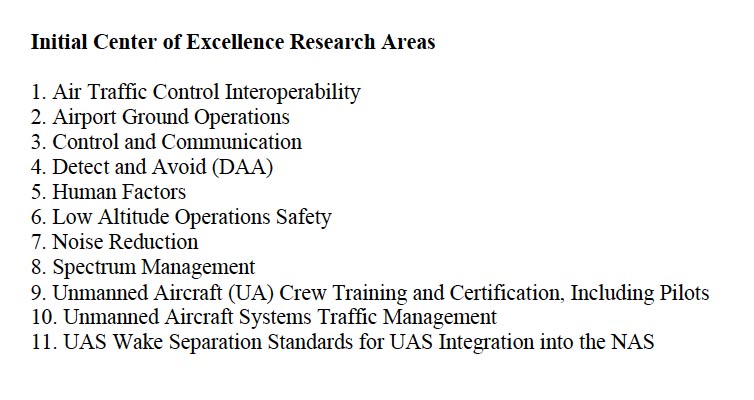

As part of their bids the teams are expected to propose projects in 11 research areas, which range from detect and avoid technology and wake separation standards to human factors and air traffic control [See inset box for full list]. The final selection of projects and tasks will not be made until after the COE team is chosen. In fact the FAA said it has yet to define the COE’s overall research agenda.

Whatever the research priorities, it appears unlikely that sufficient FAA funding will be available for all of the proposed projects. In fact, the agency has committed to providing just $500,000 annually — a key concern for would-be COE applicants, one of whom suggested that doubling that amount would still not be enough to give the FAA the results it requested.

“The Congressionally mandated $1.1M for UAS start up is hardly adequate to initiate a research initiative,” wrote one bidder whose question was posted on the FAA solicitiation website. “If research funding is so low does this indicate the FAA’s level of commitment?”

“I do think there is anticipation and hope that [the universities] are going to bring industry team members to the table that will also be funding research that will be complementary to what the FAA is [funding],” said Jon Greene, associate director for strategic planning and development at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia, which leads one of six FAA UAS test ranges.

“Pat (Patricia) Watts, who’s the director of the Center of Excellence program at the FAA has been upfront about [the funding] the whole way through,” said retired Air Force Major Gen. James Poss, who is leading bid preparation for the Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence (ASSURE Alliance). “You’re only getting $500K and that’s enough to hire a director, a small staff, and then do some really small research.”

Poss added, however, that money will probably also come from other federal agencies such as NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the departments of defense and interior. Part of the reason, he suggested, is that the COE will create a very attractive business conduit that makes it easier for agencies to contract with the schools and their partners for research.

Contractual Arrangements

Each COE member will get an individually negotiated indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contract with the FAA, explained Poss. Once arrangements are established, grants and contracts to university partners will be awarded directly. Awards made to COE core members and affiliates can be carried out without further competition during the term of the cooperative agreement, the solicitation said.

These IDIQ arrangements “are like gold in the academic world,” explained Poss. “Pretty much add any source of federal money, write a short statement work, and you’ll get work and research on your problems on UAS.”

Without the COE it could take as long as 18 months to two years to get a contract negotiated — a protracted and expensive process that federal mangers are hesitant to wade into, said Poss.

“Because it’s easier for our industry partners’ federal folks to get money to us, we find that a lot of our corporate partners are very interested in working with us once a contract is in place. They know the Air Force, Navy, or NOAA can very quickly and efficiently get us working on a research problem,” said Poss.

As a result, he suggested, “a lot more than $500,000” will become available to support the COE’s work each year. Moreover, Poss said, once the relationships are established, the COE members have the inside track on any new research work that falls in their portfolio.

“What we have found with the FAA,” Poss told Inside GNSS, “is once they declare a Center of Excellence for a particular area, they’re pretty good about only going to that Center of Excellence for particular things. For example, for advanced materials, it’s run by one of our (ASSURE Alliance) schools. They get a tremendous amount of business from the FAA working advanced composites and all that.”

Longer-Term Perspective

The connections forged through the COE could have long-term benefits for the researchers, agreed Greene.

“The FAA has other centers of excellence,” said Greene, “some of them have burgeoned into long-standing research relationships where they have been able to form these teams that now not only are solving problems for the FAA but have moved on to solving problems for industry members and other government entities.”

There are at least three credible teams preparing bids, said Greene, although he declined to name them. The winner will likely have a nationwide network of institutions and partners as part of meeting the requirement to be geographically dispersed.

Poss expects the COE competition to be intense with a lot of the action taking place on the corporate side.

“The FAA Centers of Excellence, they’re fairly old programs — been around for about 15 years,” he said. “Not that there aren’t areas to be researched in manned flight but we know an awful lot about it. On the UAS side there’re a lot of places where we get into basic research.

“For example, I mentioned detect and avoid — how do you make these aircraft achieve some type of sentience so they can sense their environment,” Poss added. “There’s a lot of basic research to be done on that, and what we’re finding is there’s a lot more companies involved in the UAS business than there are in just about any other segment of the aviation market.”

The real key, said Greene, isn’t the amount of upfront money the FAA is offering, “it’s the fact that you have a team of dedicated UAS universities that are going to be operating across the full spectrum of all the research that you need to do to safely and ethically integrate UAS into the national airspace.”

Being part of that research gives a firm a valuable insider’s perspective, said Poss. “The advantage of being part of the COE for our corporate partners is you get unique insights into what the FAA is really looking into, research, and also you get partnered up with the schools that are real experts on what’s going on in the UAS world.”